Democracy Matters, Debates Count: A report on the 2019 Leaders' Debates Commission and the future of debates in Canada

Table of Contents

- Message from the Debates Commissioner

- Section 1 - Implementing the Commission's mandate

- Section 2 – Principal findings & recommendation

- 2.1 Were the debates effective, informative, and compelling?

- 2.2 Were the debates accessible?

- 2.3 Were debate invitations issued on the basis of clear, open, and transparent participation criteria?

- 2.4 Were the debates organized to serve the public interest?

- 2.5 Principal recommendation: the establishment of a permanent Commission

- Section 3 – Beyond 2019: improving the next leaders' debates

- 3.1 Appointment of a future Debates Commissioner

- 3.2 Number of debates

- 3.3 Participation criteria

- 3.4 Measures to encourage participation

- 3.5 Debates production

- 3.6 Format and moderating

- 3.7 Venue and timing

- 3.8 Media accreditation

- 3.9 Accessibility

- 3.10 Debates promotion and citizen engagement

- 3.11 Future mandate, authority, and resources

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Appendix 1 – Leaders' Debates Commission – Order in Council P.C. 2018-1322

- Appendix 2 – Leaders' Debates Commission – Advisory Board terms of reference

- Appendix 3 – Leaders' Debates Commission – Stakeholders consulted

- Appendix 4 – Leaders' Debates Commission – Media coverage

- Appendix 5 – Interpretation of participation criteria for the Leaders' Debates

- Appendix 6 – NANOS Research – Examination of the standard for debate inclusion

- Appendix 7 – Literature Review - Canada's Leaders' Debates in comparative perspective

- Appendix 8 – Canadian Election Study – Evaluation of the 2019 leaders' debates

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 5.23 MB, 191 pages)

Message from the Debates Commissioner

Democracy matters. But there are worrying currents in societies around the world, including Canada. In 2018, Canada became a 'distruster nation' for the first time in the history of the two-decade-old Edelman Trust Survey, meaning a majority of the population did not trust government or media for public policy and news.Footnote 1 While Canada did modestly better in the 2019 survey, we are still not what Edelman would call a 'truster nation.' To combat this, we must assert that democracy and trusted democratic institutions matter: we must also make sure that they are robust. In doing so, we build trust. Complacency is our greatest enemy.

Debates count. Leaders' debates play an important role in Canada's democracy. They foster conversation, encourage engagement, and inform the electorate. They offer a rare chance to learn about each other, the people who want to lead our country, and the policies they intend to implement.

Debates are a chance to see leaders together on one stage, challenging each other's ideas and opinions, and inviting us to do the same.

Debates are a window into the world of others. As the way we communicate and consume information changes, we can become isolated from opinions outside our own. We believe debates allow us to break this bubble and learn about a variety of issues, from a variety of perspectives.

Debates are something we can participate in together, an opportunity for citizens to come together: to watch or listen to the same thing, at the same time and to gain an understanding about the issues at hand, what they mean to Canadians, and the changes our potential leaders propose. We believe that this collective experience leads to engagement and further conversation.

The Leaders' Debates Commission was created in the lead up to the 2019 election.

Our mandate was two-fold:

- Ensure that two high quality and informative debates were made accessible to Canadians from coast to coast to coast; and

- Assess whether Canadians are well served by a Commission responsible for their delivery and advise on how debates can be more effective.

The following sections report on what we accomplished, what we learned, and provide a roadmap for future debates.

I have been privileged to serve as the Commissioner for the 2019 Leaders' Debates Commission and pay tribute to an extraordinary staff and advisory board as well as a wide range of operating partners and stakeholders for carrying out this pilot project. We delivered two debates that reached and engaged Canadians like never before. More than half of the electorate tuned in to watch one of the two leaders' debates in the 2019 federal election. These debates counted: they were key moments that helped Canadians cast informed votes. Not only do debates count, they are a pivotal moment in an election campaign. They need to happen in every election, and they need to ensure that the public interest is paramount. They help us understand that democracy matters.

David Johnston

Debates Commissioner

Pl – Implementing the Commission's mandate

The Leaders' Debates Commission ("the Commission") was created to ensure debates serve the public interest and are predictable, reliable, and stable. The Commission's mandate was to organize two leaders' debates, one in each official language, and to submit a report to the Minister of Democratic Institutions who will table it in Parliament. This report is to analyze the Commission's 2019 experience and make recommendations about how debates should be organized in the future.

Traditionally, leaders' debates were organized by a consortium of the country's main television networks. Debates were considered journalistic exercises: the media determined the format, themes, questions, moderators, participation criteria, promotion, and distribution of the debates. Prominent and trusted political journalists usually moderated the debates, although this role was occasionally entrusted to respected public officials such as university presidents or judges.

The creation of a public body changed this model. By mandating a Commission to organize two leaders' debates, the Government indicated it wanted to reduce the possibility that negotiations between the political parties and the television networks would fail to produce debates, or produce debates with limited public reach. It also stated it wanted to bring more predictability and permanence to the debates as a forum for unfiltered information. Debates thus became a public trust delegated to an independent Commission. The Commission, and by extension, the producer it selected to organize the debates, became custodians of this public trust. Debates became an integral part of the democratic process, a public institution with a public trust to be protected.

The creation of the Commission also responded to a number of recurring criticisms of leaders' debates in Canada: first, that the criteria used to decide which party leaders could participate were not always publicly known nor transparently applied; second, that party leaders would sometimes use their participation as a bargaining chip in negotiations, in some cases preventing debates from being organized.

After the 2015 election, which did not have a national English-language debate with broad reach, the Minister of Democratic Institutions received a mandate to "bring forward options to create an independent commissioner to organize political party leaders' debates during future federal election campaigns."Footnote 2 The Minister, supported by the Institution for Research on Public Policy, launched a consultation process that included roundtable meetings in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Vancouver.Footnote 3 The House of Commons' Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs ("PROC") heard from 33 witnesses in late 2017 and early 2018 and reported in March 2018.Footnote 4 Both of these processes recommended the creation of a commission to ensure that debates served the public interest.Footnote 5

The Commission was created through Order in Council P.C. 2018-1322 ("OIC") and mandated to organize "effective, informative, and compelling" debates that are accessible to as many Canadians as possible.Footnote 6 David Johnston was appointed Debates Commissioner in November 2018. In accordance with the OIC, the Commissioner appointed a seven-person Advisory Board in early 2019 to reflect, as the OIC stipulated, "gender balance and Canadian diversity" and "a range of political affiliations and expertise."Footnote 7

The Advisory Board met in person or by teleconference 12 times over a 13-month period. The Commission's work was supported by a secretariat of six full- and part-time staff. The debates themselves were produced by the Canadian Debates Production Partnership ("CDPP"), following a Request for Proposals ("RFP") issued in May 2019.

A budget of $5.5 million was provided by the Government for the 2019 election cycle. As a public entity established under the Financial Administration Act, the Commission's management practices followed core public sector standards related to personnel, finance, procurement, accommodation, and reporting. While fully independent in its decision-making, the Commission received administrative support from the Privy Council Office. The Commission also received website and media expertise from Global Affairs Canada's Summit Management Office. We are grateful to both for their valued support.

The Commission's work covered nine phases:

- appearing before PROC and consulting with political parties and over 40 stakeholders with backgrounds in democratic participation, debates, and the media

- establishing a seven-person advisory board, whose involvement covered the full range of the Commission's mandate

- developing a statement of work and the design of a two-stage RFP process to select the debates producer

- launching the Commission's website and creating over 50 communications products (videos, infographics, press releases etc.)

- developing an outreach program to:

- share information and toolkits about the debates

- undertake debates participation programs with non-governmental organizations involved in democratic development

- facilitate the hosting of debate viewing experiences with 25 Cineplex theatres across the country, the WE Global Learning Centre in Toronto, the Halifax Public Library, and the McNally-Robinson Bookstore in Saskatoon

- interpreting the debate participation criteria provided in the OIC

- supporting the debates producer as required to produce the debates, including media accreditation

- consulting with stakeholders, conducting research, and hosting a January 2020 workshop on the future of debates in Canada

- producing a final report, drawing on survey responses, interviews, and research on international debates organization, carried out in consultation with academic partners

The Government specified that the Commission's report would inform whether and how a publicly-funded entity would continue to organize leaders' debates. This phased approach recognized that, in looking around the world, Canada's Commission is a rare experiment. Few democracies have election debates that are organized by a public entity solely dedicated to this purpose. Countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia have been attentive to our 2019 experience for potential application in their jurisdictions.Footnote 8

The following section reviews whether we have fulfilled our mandate and whether a publicly-funded entity should continue to organize leaders' debates in Canada.

Section 2 – Principal findings & recommendation

The OIC provided several objectives for the Commission:

- Debates should be "effective, informative, and compelling"

- Debates should be accessible to as many Canadians as possible

- Debate invitations should be made on the basis of "clear, open, and transparent participation criteria"

- Debates should be organized to serve the public interest

Additionally, in its 2019-2020 Departmental Plan, the Commission indicated it would measure the degree to which Canadians are aware of, and have access to, debates that it organized.

To review whether the Commission and its debates succeeded in achieving these objectives, we studied the 2019 leaders' debates. This included contracting independent research institutes at the Universities of Toronto and British Columbia. One of the primary resources available to these research teams was an analysis of survey responses conducted through the Canadian Election Study ("CES"). The survey included a range of questions to assess the success of the Commission's debates with the purpose of determining what citizens expected and got out of the debates.Footnote 9 We also sought feedback on alternative debate formats, and conducted research on the history of election debates in Canada and around the world.Footnote 10 After the election, the Commission consulted 28 stakeholdersFootnote 11 and hosted a workshop with 18 participants to solicit feedback from academics, civil society members, and think tanks with expertise on the topic of debates.

2.1 Were the debates effective, informative, and compelling?

Evidence indicates the Commission's debates served as a focal point for the 2019 election campaign, drawing substantially more viewers than debates in previous campaigns. Over 14 million Canadians tuned in to the English-language debate and over 5 million watched the French-language debate. These numbers are large, both in comparison to international and previous Canadian election debates.

2019 Debate viewership

2019 Debate viewership

| 2011 | 2015 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | |||

|

10,650,000 | ||

|

4,300,000 | ||

|

2,270,000 | ||

|

1,546,000 | ||

|

14,129,000 | ||

| French | |||

|

1,320,000 | 1,214,000 | |

|

985,000 | 1,318,000 | |

|

5,023,435 |

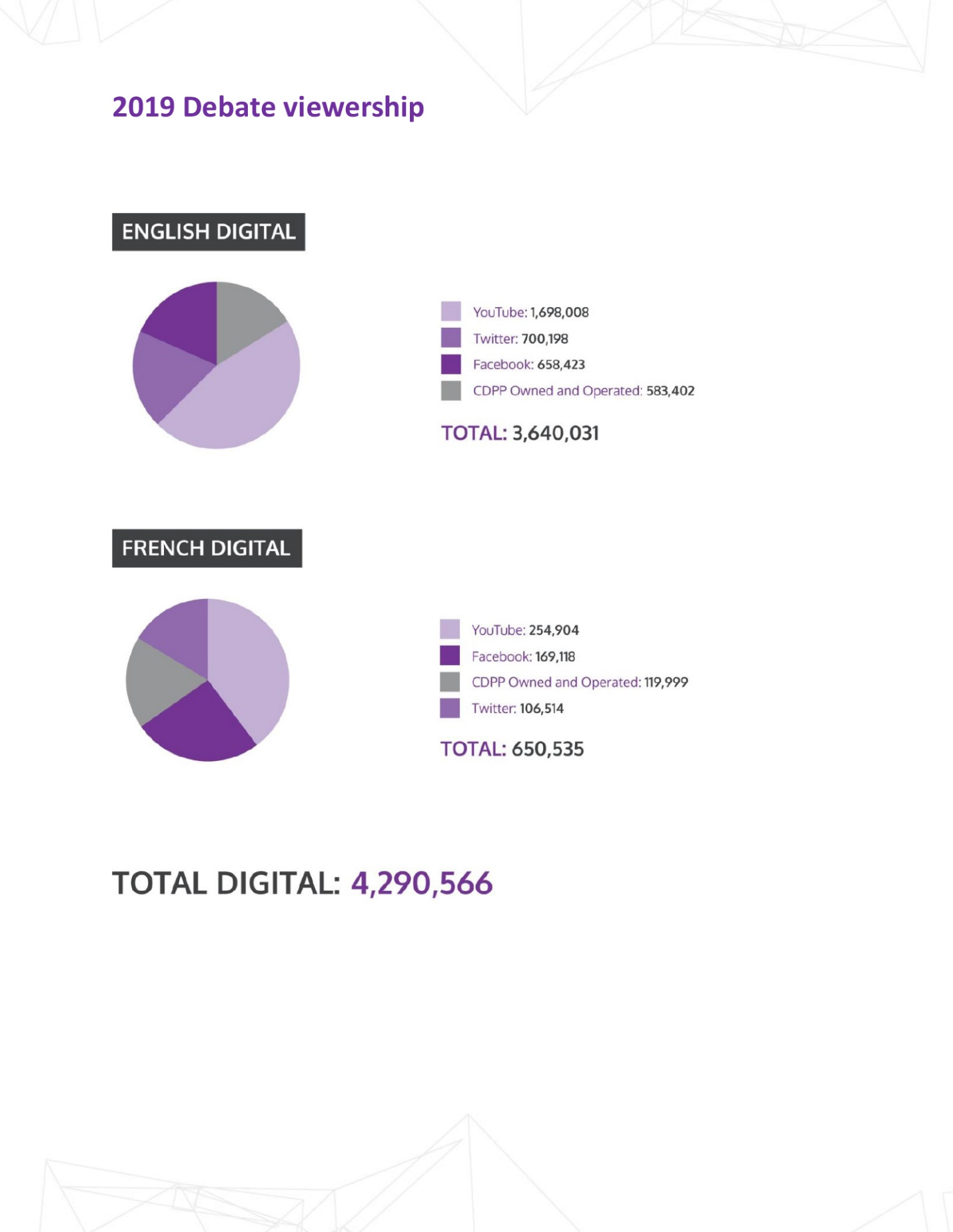

2019 Debate viewership

| English Digital | French Digital | |

|---|---|---|

| Youtube | 1,698,008 | 254,904 |

| 700,198 | 106,514 | |

| 658,423 | 169,118 | |

| CDPP Owned and Operated | 583,402 | 119,999 |

| Total | 3,640,031 | 650,535 |

Stakeholders noted the debates acted as a collective experience. This feedback is especially noteworthy given the general declines in television viewership and increasingly fragmented media audiences. Not only did more people tune in to the debates, they watched for longer. The average retention rate for the English-language debate was 52 minutes over its 120-minute duration. This is a 6% increase from the last English-language consortium debate (2011). The average retention rate for the French-language debate was 50 minutes, a 14% increase from the last French-language consortium debate (2015).

Moreover, not only did more people watch, the debates impacted their behaviour: nearly 60% of English-language viewers and nearly half of French-language viewers reported discussing the debates with other people. Polling done for the Commission also indicated watching the debates caused viewers to pay more attention to news about the federal election, to talk more about the federal election, and to learn more about party promises.Footnote 12

Viewership is one way to measure success, but there are other ways to measure if debates are effective, informative, and compelling. First, we can see the debates had an impact on social media; Twitter activity related to Canadian politics reached its peak for the entire campaign the day following the English-language debate.Footnote 13 Second, citizens said the debates made a difference; an IPSOS poll indicated that 56% of Canadians said the leaders' debates were important for their vote.Footnote 14 Third, before the debates, voting intentions were largely static. They began to change around the same time as the debates. Although it is impossible to determine what role the debates played in these shifts, this evidence is consistent with other indicators of the impact of the debates.

Initial feedback on the English-language debate was positive; the CES social media analysis found sentiment in the first 36 hours was favourable. However, there was an abrupt change about 36 hours after the debate that coincided with negative media coverage.Footnote 15 The most oft-repeated criticism concerned the format of the English-language debate and specifically the producer's choice of, and number of, moderators.

The French-language debate, by comparison, was considered more efficient and effective. It was hosted by one veteran television anchor and had a simpler format.

2.2 Were the debates accessible?

The English-language and French-language debates were available live on 15 television networks, three national radio networks, and 24 digital platforms. This is unprecedented. The debates were provided in four accessible formats and 12 languages, including Indigenous languages. Fewer than 10% of non-viewers indicated that their main reason for not watching the debates was because they were not able to access them.Footnote 16

2.3 Were debate invitations issued on the basis of clear, open, and transparent participation criteria?

In 2019, the criteria were made public in advance of the election campaign, as they were included within the OIC. Invitations to party leaders were made public, as were the leaders' responses.

The Commission also made public its interpretation of the participation criteria and how they were applied.Footnote 17

Stakeholders generally thought the criteria were applied fairly by the Commission. There was, however, considerable stakeholder consensus that the criteria should not be determined by the government of the day and should be revised to be clearer.

2.4 Were the debates organized to serve the public interest?

In 2019, the overall responsibility of delivering the debates shifted from the television networks to the Commission. The Commission became responsible for their success or failure.

Mindful of the importance of high journalistic standards and independence, the debates producer was chosen through an RFP.

The RFP reflected the values permeated in the Commission's mandate: inclusiveness, democratic education, high journalistic standards, cost effectiveness, organizational experience, and accessibility especially for people with disabilities, people living in official language minority communities, and residents of remote regions.

The debates producer was responsible for the promotion, production, and distribution of the debates including: format, moderating, themes, and questions. The Commission was not present during negotiations with the political parties. The debates producer briefed the Commission regularly on the progress of negotiations and preparations for the debates.

Post-debate consultations showed there is widespread agreement that an independent and impartial Commission should play an important role in ensuring the public interest is given full consideration in debate organization.

2.5 Principal recommendation: the establishment of a permanent Commission

We believe the above findings indicate the Commission fulfilled its mandate. By the standards set out in the OIC, the English-language debate held on October 7, 2019 and the French-language debate held on October 10, 2019 achieved their objectives.

There is also broad support for the continued existence of a Commission, provided that measures are maintained to ensure its independence, impartiality, and transparency. A range of stakeholders also concluded that a future Commission should have a more active role in some aspects of debate format.

Entrusting the Commission with the mandate to hold two debates in 2019 may well have changed the nature and scope of debate organization in the future. While debates must meet high journalistic standards, they are more than journalistic exercises; they are democratic exercises. This change in perspective, which was repeated throughout the Commission's consultations, goes beyond semantics. It speaks to the fact that the Commission is mandated with a public trust, and that its accountability is to the people of Canada. It also makes the Commission responsible for the success of the debates in their entirety. Given this was a first for Canada, the fact that a range of voices argued a Commission should be more involved in the future supports the rationale for its continued existence.

The financial uncertainty of media organizations is another reason to consider a permanent Commission. In 2019, the Commission financed elements of the debates including the public venue, some distribution costs, interpretation, and outreach programs. Producers provided significant in-kind contributions related to debates promotion and production.

We conclude leaders' debates are important to the democratic process and should be a predictable feature of our election campaigns.

With the rest of this report, we make recommendations based on our 2019 experience, to inform both the makeup and mandate of a future debate authority and the debates themselves.

PRINCIPAL RECOMMENDATION: We recommend the establishment of a permanent, publicly-funded entity to organize leaders' debates.

Section 3 – Beyond 2019: improving the next leaders' debates

This section provides recommendations that seek to improve the legitimacy, role, mandate, structure, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of a future Commission. This permanent, publicly-funded entity could either take the form of the current Commission, or it could be another publicly-funded debate authority. For the purpose of readability, we use the term Commission.

3.1 Appointment of a future Debates Commissioner

In 2019, the Commission was headed by a Debates Commissioner, who was a part-time OIC appointee. The Government selected the 2019 Debates Commissioner, but the process did not include consultation with opposition parties. The Government nominated the Debates Commissioner, who then appeared before the House of Commons' Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs to allow political parties to study the nominee's credentials. Following this appearance, the Debates Commissioner was appointed to the office.

Consultations following the debates revealed that this approach was unsatisfactory not only to opposition parties, but to a broad range of stakeholders.Footnote 18 The lack of support for the appointment process was a significant potential constraint on the Commission's legitimacy. Despite this, most stakeholders acknowledged the Debates Commissioner carried out his work in an impartial and independent manner and appreciated the transparency of the Commission's decisions.

We believe the role of the Commissioner is an important one and should be maintained. We conclude the appointment should be validated through consultation with opposition parties. This gives the Commission visibility and profile as well as credibility for decisions on things such as the participation criteria. The specific rationale for those decisions would rest with the Commissioner, rather than the government of the day, in order to increase transparency and minimize any perceptions of political bias. The role of the Commissioner should be subject to a term whose end date is separate from the end date of a particular election cycle.

RECOMMENDATION #1: The Commission should be headed by a Debates Commissioner whose appointment process involves consultation with the registered political parties represented in the House of Commons.

3.2 Number of debates

Many of the features of debates such as the format, venue, timing, and participation of leaders will be influenced by the number of debates organized by a future Commission. In 2019, the Commission had a mandate to organize two debates: one in each official language. These debates, in the words of the OIC's preamble, were supposed to "benefit from the participation of the leaders who have the greatest likelihood of becoming Prime Minister or whose political parties have the greatest likelihood of winning seats in Parliament."

Some stakeholders and commentators suggested the two debates in 2019, particularly with six participants, did not provide enough speaking time for each participant and did not allow for sufficient interaction between the candidates who were considered most likely to become Prime Minister. As a result, we gave some consideration to the possibility of organizing four debates in the future: two in each official language. The first two in English and in French would bring together a smaller group, up to four leaders, with a reasonable chance of becoming Prime Minister. The second two debates would include the party leaders, perhaps five or six, who meet a lower threshold of participation criteria, as in the 2019 debates.

However, most stakeholders advised that adding more debates could create new problems. For instance, it could necessitate the development and application of two different sets of participation criteria. More debates might also dilute the viewing audience and detract from the shared experience of debates. Political parties have also voiced concerns about scheduling additional debates, with more than two debates historically only being held during longer campaign periods (such as 2005 to 2006 and 2015.) This compounds the potential that increasing the number of debates organized by a future Commission might make it even more difficult for other organizations to secure the participation of party leaders in their debates.

While there may be future demand for additional debates related to specific issues (in our view a very desirable outcome), these could be hosted by other organizations. In 2019, the Commission was instructed to "conduct its activities in a manner that does not preclude other organizations from producing or organizing leaders' debates or other political debates." Maclean's and Citytv organized an English-language debate on September 12, 2019 involving Elizabeth May of the Green Party of Canada, Jagmeet Singh of the New Democratic Party, and Andrew Scheer of the Conservative Party of Canada. Justin Trudeau of the Liberal Party of Canada did not participate. On October 2, 2019, TVA hosted a French-language debate involving Yves-François Blanchet of the Bloc Québécois, Jagmeet Singh of the New Democratic Party, Andrew Scheer of the Conservative Party of Canada, and Justin Trudeau of the Liberal Party of Canada.

Several stakeholders noted the Commission's existence may have created the semblance of 'official' debates that party leaders could use in order to decline invitations to non-Commission debates. In particular, a separate debate on foreign policy was cancelled. The Munk Centre stated that this was due to Justin Trudeau of the Liberal Party of Canada's decision not to participate. However, other stakeholders observed that some of these conflicts are the result of overemphasizing the role of party leaders in Canadian democracy, noting that other organizations might effectively produce debates featuring cabinet members and opposition critics.

In 2019, the two debates organized by the Commission were held in the same location for cost effectiveness, and because neither the political parties nor the debates producer were enthusiastic about the idea of travelling between debate days. Future Commissions may want to consider hosting the English-language and French-language debates in different locations and perhaps outside of Ontario and Quebec.

RECOMMENDATION #2: The Commission should organize two publicly-funded debates, one in each official language.

3.3 Participation criteria

In 2019 the Commission did not set the participation criteria for the debates that it organized. Instead, the task was to interpret and apply the mandated criteria laid out in the OIC. Political parties had to meet two of the following criteria in order to participate:

- Criterion (i): the party is represented in the House of Commons by a Member of Parliament who was elected as a member of that party;

- Criterion (ii): the Commissioner considers that the party intends to endorse candidates in at least 90% of electoral districts in the general election in question;

- Criterion (iii):

- the party's candidates for the most recent general election received at that election at least 4% of the number of valid votes cast; or,

- based on the recent political context, public opinion polls and previous general election results, the Commissioner considers that candidates endorsed by the party have a legitimate chance to be elected in the general election in question.

After consulting the political parties, the Commission published its interpretation of the criteria. We stated that criteria (i) and (iii)(a) did not require an extensive assessment because they are based on the review of objective evidence. Criteria (ii) and especially (iii)(b), on the other hand, did require assessment.Footnote 19

In the case of five political parties, the application of the criteria was straightforward. We issued invitations to these parties' leaders on August 12, 2019, almost two months before the debates.Footnote 20 None of these five invitations required the interpretation and application of criterion (iii)(b).

However, determining whether to invite a sixth political party, the People's Party of Canada ("PPC"), required further assessment. Rather than inviting the leader of the PPC in August alongside the other five leaders, the Commission sought additional and more current information, including from the PPC and from polling conducted on our behalf, before making a determination of whether more than one candidate endorsed by the PPC had a legitimate chance of being elected. We issued an invitation to the leader of the PPC on September 16, 2019.Footnote 21

This decision to invite the leader of the PPC created some controversy,Footnote 22 although, in post-debate consultations, most people generally agreed the criteria as set out in the OIC were fairly and transparently applied by the Commission.

Nevertheless, two consistent concerns were expressed:

- The Government of the day is ill-placed to set participation criteria for leaders' debates, given the perception of a conflict of interest caused by the Prime Minister's future participation in the debates; and

- The criteria as written introduced a high degree of ambiguity, which detracted from the certainty that a Commission was intended to provide to debate organization.

We conclude both of these concerns are valid. The fact that debate participation criteria were laid out in advance of the election was intended to make the process transparent, impartial, and predictable as well as to ensure public accountability. These objectives are sound and important. The use of public participation criteria in 2019 represented a step forward for debate organization in Canada, especially as it relates to transparency.

Improvements could be made to the process to further realize these objectives.

First, to ensure impartiality, the determination of debate participation criteria should not rest with the government of the day. No level of transparency and fairness on the part of a Commission will ensure that the overall debate organization process is viewed as non-partisan if the participation criteria are perceived as being set by one interested party.

Second, to ensure predictability, efforts must be made to remove undue ambiguity from the interpretation of the participation criteria. Criterion (iii)(b) required an interpretation of a number of components, including what number of "candidates" were needed to meet the threshold and what was meant by "legitimate chance." More fundamentally, it also required an overall assessment of the electability of candidates, essentially in all 338 electoral districts.

Each of these items provided a possibility for observers to arrive at different conclusions as to whether a party did or did not meet the stated criterion. The Commission considered a range of evidence to support the conclusions it reached in interpreting the criteria as provided. Nevertheless, this level of interpretation, coupled with the need to collect evidence on electability, did not lead to a process that was completely satisfactory.

We conclude that setting the criteria should be a responsibility of the Commissioner, but we include some analysis from our 2019 experience here for potential future Commissioners to consider.

No consensus emerged from consultations on specific participation criteria. We heard differing opinions about whether the debates should:

- feature candidates who are more likely to be Prime Minister or those who reflect a broad range of public opinion

- emphasize only national concerns or make space for party leaders representing regional considerations

- feature participation criteria that look backwards or explicitly avoid privileging incumbency

- feature participation criteria that reflect the principles of Canada's parliamentary system of electing individuals from local constituencies to Parliament and not directly electing a Prime Minister

While there was little support for either the existing criteria or the total absence of criteria, we heard often that there is likely no perfect set of criteria.

Responses to the CES survey reveal that the three types of participation criteria with the most support are, in order from most popular to least popular:

- number of candidates running for a party

- poll results

- number of MPs that a party has in the House of Commons

However, using the number of candidates running for a party alone to determine participation could disadvantage regional parties, some of which have historically achieved success and parliamentary influence. Put differently, the number of candidates a party is able to field may not be an indicator of future success or popular support for a party. Looking at the number of elected MPs alone, on the other hand, risks hindering the success of emerging parties and reinforcing the influence of historically successful parties. In sum, who should be in the debates and how they should be chosen is a matter that remains without a clear answer.

As we approached this task in 2019, we carefully considered the language of the OIC. In particular, one clause in the preamble stated that debates should "benefit from the participation of the leaders who have the greatest likelihood of becoming Prime Minister," yet also, of leaders "whose political parties have the greatest likelihood of winning seats in Parliament." Then, in the body of the OIC, the specific criterion declared that a leader whose party's candidates "have a legitimate chance to be elected" be allowed to participate, thus further tilting towards more participants reflecting a wider range of political parties and interest. These two objectives, one narrowly aimed at the most likely Prime Minister and the other reflecting broader inclusiveness and a range of views, are somewhat at odds. A focus on the former would suggest a smaller slate of debate participants, perhaps as small as two or three in the Canadian context. A focus on the latter would broaden the stage to include as many as five or six leaders.

While our decision focused on the interpretation of the specific criteria provided in the OIC, we believe debates organized by a future Commission should, through its choice of invited leaders, focus on potential representation in Parliament and not on potential Prime Ministers. Canada does not have a presidential system, and leaders' debates should therefore feature leaders of political parties that are likely to be an important part of public policy making in the House of Commons.

In 2019 one criterion in the OIC required focusing on electability to assess the legitimate chance of candidates being elected. It was concluded that if more than one in four voters in a riding considers voting for a party, that party has a reasonable chance to elect its candidate. In our postmortem review, we commissioned further research in the area of electability from Nanos Research.Footnote 23 That analysis suggests that a standard of 40% "willing to consider" may be a more robust indicator of electoral success. However, rather than assess the potential electability of individual candidates, we suggest future Commissioners move towards objective criteria.

The goal of reducing ambiguity, coupled with our view that debate participation focus on potential representation in Parliament, suggests the possibility of using a combination of two measures: party leaders would be invited if their party's candidates received at least 4% of votes cast in the previous election, or, if the party has at least 5% national support in an aggregate of current public opinion polls. The timing of the public opinion polls should balance the need for the Commissioner to make decisions based on the best data available to make an assessment, with the need for debate producers to have sufficient time to produce high-quality debates. The asymmetry of 4% of actual votes versus 5% in polls is accounted for by the fact that not all support indicated in a poll translates into actual votes.

We recognize that a future Debates Commissioner would likely need to do further analysis on the precise thresholds and methods, including whether a level of regional support as opposed to, or in addition to, national support may supplement the above two potential criteria. It is our belief that the use of these or similar criteria would achieve the objective of ensuring the participation of those leaders that are likely to play a role in Parliament. Additionally, the use of such criteria recognizes there is value in including party leaders with either a sizable historical or potential support within the Canadian public, as opposed to requiring a future Commission to focus on riding-level results.

The use of criteria such as these seem to be consistent with public opinion on debate participation. For instance, polls in 2008, 2011, and 2015 indicated a majority of Canadians (often more than 70%) wanted to see the Green Party's Elizabeth May in the leaders' debates. The party consistently polled around the 5 percent markFootnote 24 before the election.

RECOMMENDATION #3: The Debates Commissioner should set the participation criteria for the debates; these criteria should be as objective as possible and made public before the election campaign begins.

3.4 Measures to encourage participation

The Commission's capacity to ensure the participation of leaders may be proportional to its ability to organize debates that draw audiences too large for political parties to ignore. In the past, leaders haven't always participated and this can lead to debates being cancelled (2019 Munk Debate, leaders' debates in 1972, 1974, 1980, and 2015.) Additionally, party leaders may strategically use their participation as a bargaining chip in format negotiations, or to request concessions, such as the exclusion of other leaders.

The requirement that the Commission "ensure that the leaders' responses to the invitations to participate in the leaders' debates are made publicly available before and during the debates" was designed to encourage party leaders to participate. Yet, the debate examples noted above demonstrate that publicity may not be sufficient to motivate participation.

However, there was little support for the notion of compelling party leaders to participate. Our 2019 experience leads us to believe the best ways to encourage participation are:

- deliver a large audience for the debates

- engage with leaders and political parties in advance of the election

- create a climate of expectancy and stability

- make debates invitations and responses from parties transparent

RECOMMENDATION #4: The Commission recommends that the government encourage rather than compel leaders to participate.

3.5 Debates production

The Commission's relationship with the CDPP was productive and positive. Effective debates require the right combination of players, including broadcasters, digital platforms, and high-quality journalists. The CDPP provided leading capability and significant in-kind contributions valued at more than $3 million. The CDPP brought together an unprecedented number of partners, with excellent results in the areas of audience reach, retention rate, and accessibility.

We also believe it is important that smaller entities with innovative ideas are able to come forward. The RFP was weighted towards innovation rather than simply size. The CDPP emerged as the clear winner for the 2019 exercise for a variety of reasons, the principal ones being experience, technical capability, and reach; the CDPP offered promotion and distribution to ensure the debates reached the greatest number of Canadians.

As for the RFP process, while it was of high quality it was often cumbersome and prone to delays. This is problematic because the time frame for organizing debates is limited, particularly in a minority government scenario.

Once contracted, the CDPP took full responsibility for the promotion, production, and distribution of debates while maintaining regular communications with the Commission.

As described above, the Commission was not involved in the format, moderating, themes, or questions of the debates. That responsibility was delegated to the CDPP. A future Commission could take a more hands-on approach to producing debates, closer to the model used in the U.S. However, there are some disadvantages to this model that should be considered:

- The extensive expertise and experience that is required to produce debates would be difficult to build "in-house" in a short time period.

- It would require a large staff and infrastructure, which would be less cost-effective than the existing model.

- Having a future debate authority produce the debates from end-to-end would mean being fully responsible for the journalistic exercise.

While we do not recommend future debates be produced "in-house," we do believe a future Commission should be better able to represent the public interest. To do that, it should be more involved in decisions about the debates.

High journalistic standards and journalistic independence are essential to the credibility of debates. However, the Commission believes these concepts should be reinterpreted to allow the Commission a greater involvement in format and moderating.

Traditionally, the journalistic exercise encompassed the choice of format and moderating as well as themes and questions. The Commission believes it can have a greater say in format and moderating without encroaching on the journalistic independence of the producer. The producer would continue to have authority over the themes discussed during the debates and the questions posed by moderators. The Commission also believes the way to achieve best practice in terms of format and moderating is to maintain a constructive and productive relationship with potential producers, experts, and political parties between elections.

RECOMMENDATION #5: The Commission should select the debates producer through a competitive process, emphasizing the need for high journalistic standards, creativity, innovation, experience, technical expertise, wide distribution, and accessibility.

3.6 Format and moderating

There is widespread agreement that the Commission's French-language debate fared better than the English-language debate. The existence of two distinct Commission-organized debates serve as a kind of natural experiment, making it possible to gain insight about format and moderating choices.

There was considerable negative media coverage of the English-language debate format.Footnote 25 Critics said:

- there were too many participants, including both moderators and party leaders

- the format itself was too complicated

- the rigid time limits reduced spontaneity

- the format of the debate allowed leaders to avoid answering questions

- the format of the debate allowed leaders to talk over and interrupt one another

The reaction to the French-language debate was more positive, with many praising the performance of the moderator.

The choice of moderator is an important one, and future Commissions should pay considerable attention to how this decision is made. In addition, the Commission should ensure a format that allows moderators to challenge leaders on the accuracy and relevance of their answers.

Citizens appear to have been less critical of the debate format than media. A majority of surveyed citizens agreed both debates were informative, helped them better understand the issues, and helped them better differentiate between the parties. Responses were generally more positive for the French-language than the English-language debate. For both debates, clear majorities observed that the moderators treated leaders fairly and asked good questions, but that the moderators could have done more to correct factual inaccuracies and intervened with more penetrating follow-up questions to stop leaders from avoiding questions.

It is also not clear that citizens are opposed to debates with more participants. While survey results suggest a majority (63%) agreed the English-language debate had too many leaders participating, the results for the French-language debate indicate only 41% of respondents thought there were too many participants on stage. This suggests six participants is not too many in the eyes of viewers, depending on the approach taken to format and moderating.

Debate format should avoid unnecessary complexity. The moderator, and the format they are working within, must have the capability to:

- maintain proper time allocation

- ask follow-up questions that ensure leaders answer the questions posed

- avoid undue interruptions between leaders

- avoid cross-talk (leaders talking over one another)

- ensure civil discourse

Neither the Commission nor political parties should be involved in choosing the themes or the questions.

RECOMMENDATION #6: The Commission should reserve the right of final approval of the format and production of the debates, while respecting journalistic independence.

3.7 Venue and timing

Both debates took place at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Québec. The venue provided a sense of place, but some stakeholders noted this came at the cost of the logistical simplicity that would be provided by a dedicated television studio. A number of regional segments were included to reflect Canada's diversity, but these needed to be produced more carefully to achieve a feeling of national importance while showcasing regional diversity and local identity.

The Commission agreed with those consulted that there was value to having a live audience. However, some stakeholders said it was awkward to have the audience seated behind the participants, and others wanted to see more questions from audience members.

The English-language debate took place October 7, 2019 at 7 pm ET and the French-language debate was held on October 10, 2019 at 8 pm ET. There is consensus that having the debates take place roughly two weeks prior to election day, in this case, October 21, was appropriate, as it was before the advance polls and many voters do not begin to follow the campaign until relatively late. Political parties generally supported having at least a day between debates, although this increased the cost of production.

More controversial was the choice of timeslot for the English-language debate, which began at 4 pm PT. The existence of six time zones across Canada makes scheduling difficult. We believe an 8 pm ET start time, as used in the French-language debate, or a consideration of holding the debate on a weekend is preferable.

English-language broadcasters appear reluctant to carry debates during prime time in Ontario and Québec, citing concerns about lost revenue. The Commission should work with the debates producer to see if there are better ways to serve people in different time zones.

The Commission could also examine other ways to take account of Canada's six time zones, such as hosting the two debates in different locations, encouraging ways for citizens to interact with the debates outside of the live broadcast, and ensuring regional locations are represented in the themes and remote locations.

Finally, the Commission should make public the dates and times of the debates as early as possible, to allow other organizations interested in holding debates to plan around them.

3.8 Media accreditation

One element of debate organization that remained in the purview of the Commission was media accreditation. The 2019 debates created interest from journalists and media organizations interested in covering the events. The Commission received more than 200 requests for accreditation.

In its desire to provide an environment conducive to professionally responsible coverage, the Commission consulted with the Parliamentary Press Gallery, and ultimately decided to limit accreditations to professional journalistic organizations.

Four organizations were turned down because the Commission concluded they were involved in political activism. Two of the four organizations challenged the decision in Federal Court. They obtained an injunction requiring the Commission to allow them to cover the debates and press availabilities of the leaders immediately following the debates. The Court ruled on an interim basis that, among other things, the Commission did not follow the rules of procedural fairness in respect of its denial of accreditation and ordered the accreditation of the two organizations. As at the date of this report, the application for judicial review remains before the Federal Court.

3.9 Accessibility

For leaders' debates to be a democratic exercise, citizens must be able to access and experience the debates in a way that is accessible.

The English-language and French-language debates were available on 15 television networks, three national radio networks, and 24 digital platforms. Together, these networks are accessible to nearly all Canadians. As of 2017, 84% of Canadians have access to high-speed internet capable of streaming videos, but rural households and Indigenous communities are less likely to have such access.

As mentioned above, fewer than 10% of the people who did not watch the debates indicated that the main reason for not doing so was because they were not able to access them. However, there is some evidence that rural Canadians were more likely to report being unable to access the French-language debate.Footnote 26 Analysis of data from CES found no evidence that disability, official language minority status, or age made the debates inaccessible to non-viewers.Footnote 27

Digital viewership

The vast majority of viewers reported they watched the debate on television. Online streams on Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter accounted for 83% of digital views, with the distributor's own digital video platforms accounting for approximately 16% of views.

| English-language debate | French-language debate | |

|---|---|---|

| TV | 85% | 93% |

| Radio | 5% | 2% |

| Online | 10% | 5% |

Language viewership

The debates were available in 10 languages (in addition to French and English), including Indigenous languages Dene, Ojibwe, Plains Cree, East Cree, and Inuktitut.

| English-language debate | French-language debate | |

|---|---|---|

| Arabic | 11,000 | no data available |

| Cantonese | 80,000 | 27,000 |

| Dene | not offered | 485 |

| East Cree | not offered | 224 |

| Inuktitut | 7,853 | not offered |

| Italian | 23,000 | 125,000 |

| Mandarin | 70,000 | no data available |

| Ojibway | 1,087 | not offered |

| Plains Cree | 8,613 | not offered |

| Punjabi | 15,000 | 48,000 |

Accessible formats

The debates were also available in four accessible formats (Closed CaptioningFootnote 28, Described Video, ASL, LSQ).

| English-language debate | French-language debate | |

|---|---|---|

| ASL | 1,713 | 257 |

| Described Video | 4,056 | 523 |

| LSQ | 1,087 | 901 |

Viewership of the various languages was variable, but the Commission believes this is an important initiative. Stakeholders indicated the Commission's efforts to make debates accessible demonstrated respect for Canada's diverse communities and also served as an inspiration for organizers of local debates across the country to make their own debates more accessible. In particular, interpretation into several Indigenous languages is consistent with the Government of Canada's broader interest in preserving, protecting, and revitalizing Indigenous languages.Footnote 29 However, several groups indicated the Commission could have done more targeted outreach or advertising, for instance, in ethnic media outlets, to ensure Canadians who might benefit from these accessibility initiatives were aware of their existence. A future Commission should continue to look for ways to work with networks that offer programming in languages other than English and French, in an effort to reach minority language communities, as was done in 2019 with OMNI television. A future Commission could encourage Indigenous radio stations to carry the debates, either in an official language, or in one of the Indigenous languages being offered.

We believe that interpretation is an important investment in the future of debates in Canada, particularly to reach communities who have traditionally faced barriers to inclusion in the democratic process. There was also widespread agreement that many of the Commission's accessibility initiatives would not have happened without public funding.

RECOMMENDATION #7: The Commission should ensure the debates are available in languages other than French and English, paying special attention to Canada's Indigenous languages.

3.10 Debates promotion and citizen engagement

The Commission managed its outreach to work in tandem with the CDPP's promotion. We provided more than 40 pieces of original content to various organizations representing a wide scope of interests, challenges, and barriers. The goal was to raise awareness about the debates, promote new features (such as languages and accessibility), and promote why debates matter.

We contracted several organizations to produce original educational and promotional content, and also worked with libraries, bookstores, and movie theatres to broadcast the debates in cities across the country.

The Commission engaged with a large number of organizations, but this had less impact than the role of the CDPP on promotion, as the organizations we worked with had limited capacity and resources. Only about 38% of Canadians reported an awareness of the debate prior and even fewer could accurately recall the dates of the debates.Footnote 30 This suggests many people still find the debates by flipping through television channels or hearing about it on the same day. It is therefore important that the debates be available on as many channels and digital platforms as possible.

Approximately 10% of those who watched the English debate with others and 13% of those who watched the French debate with others, did so as part of an organized event.Footnote 31 It is difficult to assess how much of this viewing activity is related to the Commission's outreach efforts, as the survey respondents didn't specify if the event they attended was one of the Commission's outreach events. The survey data are also unlikely to fully capture students under 18 who may have watched part or all of a debate as part of the Student Vote program run by CIVIX, which operated in 9,500 schools across Canada. These experimental, scalable, and innovative approaches merit further development and resourcing.

3.11 Future mandate, authority, and resources

The success of a future Commission is dependent on a number of factors. Some of these have been discussed previously, but we refer to these here again to guide further analysis. A future Commission should ensure:

- that its head, the Debates Commissioner, is selected in a manner that provides for consultation with opposition parties

- that it operate and be understood to operate in a manner that ensures its decision-making is recognized as impartial and free from any political influence

- that it be responsible for submitting a final report after each election cycle and present the report directly to Parliament without delay upon its completion

- that it be entrusted with enough responsibility and influence to be an effective guardian of the public trust by playing an active role in the production of the debates

- that it maintain a constant and constructive relationship with political parties, potential debate producers, and other stakeholders

- that the journalistic independence of the media participants be ensured

- that the debates be considered credible, informative, effective, and compelling

- that it operate transparently and seek to involve the public in its decisions

- that it be cost-effective

- that it build a recognized expertise in evolving debate formats and practices, here and abroad, to guarantee the best debate experience for Canadians

The 2019 Commission was well-served by the mandate provided in its OIC. Stakeholders commented that the core of the Commission's mandate, which was to impartially and transparently promote, organize, and review two debates in the public interest, was well calibrated. There was little appetite for expanding the Commission's mandate, with some stakeholders noting that it is still a new entity.

The initial OIC captures the scope of a future entity's task, should one be established.Footnote 32 The language stating the Commission was to be guided "by the pursuit of the public interest and by the principles of independence, impartiality, credibility, democratic citizenship, civic education, inclusion and cost-effectiveness" was particularly helpful in guiding the Commission's task in 2019. Provisions for research, assessment, and awareness-raising also equipped the Commission with the tools needed to support the delivery of its core functions, and similar provisions would be central to its continued operations.

Below are some areas that could be adapted, should our recommendations be adopted.

Participation criteria: section 2(b)

This section might be adapted, should our recommendation that a future Commissioner set the participation criteria be adopted. Specifically, it could lay out the principles and values that should guide a future Debates Commissioner's approach to debate participation, rather than specific metrics to interpret. The Commissioner would then determine well in advance of the election debates the specific participation criteria. Provisions might also be drafted to ensure a future Debates Commissioner provides for timely and transparent decisions and that reasons are publicly provided.

Other debates: section 2(i)

In 2019, the Commission did receive inquiries from a number of groups and organizations that were seeking to organize debates of their own. They included requests for the Commission to liaise with political parties on the organizer's behalf, or to offer approval of their debates as well as requests for monetary assistance. We adopted a policy that no financial support would be provided for the actual organizational cost of other debates. This policy was adopted to focus Commission expenditures on the delivery of the other elements of its core mandate including its own debates. It was also due to the inherent difficulty in establishing criteria that would be applied to determine which debate organizers would be eligible and which would not. While the Commission should encourage other debates, it should not be a grant-making body.

Calls for proposals: section 5(2)

This section provided a helpful frame to guide the 2019 RFP, but might be examined to ensure they align with our earlier recommendations that the Commission be entrusted to actively assert its role to ensure debates fulfil their function as a democratic exercise, rather than principally a journalistic one.

Governance: sections 6 to 9

We have provided reasons why a future entity should continue to be headed by a Debates Commissioner. The provisions describing the Debates Commissioner should consider the potential to add language outlining consultations with political parties. Provisions in the Canada Elections Act with regard to the appointment of the Broadcasting Arbitrator may be a useful starting point.Footnote 33

The Commission established the Board in accordance with the OIC's provision mandating the Advisory Board's "composition is to be reflective of gender balance and Canadian diversity and is to represent a range of political affiliations." Our Board proved essential to the successful fulfillment of the Commission's mandate, and provisions should be made for a future Commission to ensure it continues to rely upon such thoughtful external viewpoints and the ability to test potential decisions. The inclusion of Board members with political experience was a key contributor to the value provided to the Commission.

In terms of institutional makeup, a future Commission needs to be designed to achieve the outcomes listed at the start of this section, with a particular focus on operational independence, both real and perceived, cost effectiveness, and administrative agility.

The 2019 Commission enjoyed complete operational freedom. The only interactions to occur with the Minister of Democratic Institutions (the Minister responsible for the Commission) involved discussion with regards to the application of, and potential need for, exemptions to Treasury Board policies.Footnote 34 No direction was received nor sought with regards to Commission decision-making. Nevertheless, the Commission's independence was questioned by some observers, owing in part to the selection process of the Debates Commissioner.

Cost effectiveness and administrative agility

The current institutional model of the Commission (i.e. a government departmental agency under I.1 of the Financial Administration Act) may not be optimal for a future entity. In particular, the need to advance a procurement process for debate production under tight timelines as well as contracts to fulfil its mandate to raise awareness, proved challenging in the Commission's current operating environment. Nevertheless, owing to lessons learned and increased familiarity on the part of Commission personnel and other government departments of the Commission's mandate, there are opportunities to streamline and improve the RFP process in the future.

Summary of expenditures

A budget of $5.5 million was provided by the Government for the 2019 election cycle. Of this amount, approximately $4.1 million was spent in five categories:

- Research, evaluation, and outreach initiatives: this included research undertaken by the Canadian Election Study consortium and UBC's Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions and limited partnerships related to the preparation and dissemination of debates promotion materials and debate-viewing events in major centres across the country.

- Professional services: this included polling in relation to debates participation criteria, legal advice, web coding, and report editing and layout.

- Contract for incremental costs for debate production: certain production costs related to elements such as increased accessibility, language interpretation, and venue organization were reimbursed by the Commission.

- Commission salaries and administrative expenses: these expenses related primarily to employee services (six full- and part-time staff) and support to the seven-person Advisory Board.

- Privy Council administrative expenses: this included the provision of back-office support in relation to procurement, finance, information technology, personnel, and accommodations.

| Activity | Preliminary estimate ($ millions) |

|---|---|

| Research, evaluation and outreach initiatives | 0.3 |

| Professional services | 0.5 |

| Contract for incremental costs for debate production | 1.7 |

| Commission salaries and administrative expenses | 1.2 |

| Privy Council Office administrative expenses | 0.5 |

| TotalFootnote 35 | 4.1 |

In addition, the Commission benefitted from significant in-kind contributions from the debates producer and partner organizations. These additional contributions, valued at over $3 million, involved extensive debates promotion by the CDPP, special measures to ensure greater reach and accessibility, design and hosting of the Commission's digital presence by Global Affairs Canada's Summit Management Office, hosting of debate-viewing events, and partner outreach.

There was broad agreement that the Commission's continued capacity to organize accessible, inclusive debates with broad reach will need to rely on sufficient funding. In particular, members of the CDPP noted that interpretation services, accessibility, and high production values might not have been achievable without the Commission's direct financial support. The ability to draw on stable funding will also be necessary for the Commission to fulfil its contracting and staffing requirements prior to the organization of debates.

Future mandate

Most stakeholders believe the Commission should continue to some extent between elections, increasing staffing some months prior to the debates. This would allow the Commission to preserve institutional memory, determine or interpret participation criteria outside of election periods, and consult with citizens and stakeholders to prepare for future debates (e.g. preparing RFPs). These functions are particularly important in the case of a minority government situation where the Commission may be required to organize debates on short notice and increase staff urgently. Consideration should be given to the Commission regarding the Public Service Employment Act and its status related to the "core public service" to potentially benefit from the possibility of secondments or assignments in the lead-up to the debates.

As the custodian of the debates, a future Commission should also monitor and keep abreast of evolving best practices in debates in Canada and elsewhere. This would ensure that debates are organized with the best expertise and most current understanding of debate formats, distribution, and the changing media environment. Sharing this information widely and regularly with producers and political parties would encourage a commitment to best practice and to the most useful democratic experience possible for the viewing public.

As further recognition that debates are a public trust, several stakeholders emphasized the critical task of a future Commission to determine ways to consult Canadians periodically on their views about debates, whether through surveys, focus groups, or other types of consultation.

There are a range of models that enable a future Commission to be mandated with these responsibilities and that would achieve the stated goals of independence, cost effectiveness, and administrative agility. Several stakeholders raised the possibility that the Commission might be organized as an Agent of Parliament due to its greater perceived independence. Others referred to entities such as the Broadcasting Arbitrator, the Canadian Human Rights Commission, the Pan-Canadian Expert Initiative, and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation as examples of entities whose governance contributes to both real and perceived independence from the government of the day.

Finally, a future Commission should prepare a report after each election cycle and this report should be delivered directly to Parliament.

RECOMMENDATION #8: The Commission should ultimately be established through legislation (or similar mechanism) in order to prioritize greater continuity, transparency, and access to resources. Its institutional makeup should prioritize real and perceived operational independence, cost effectiveness, and administrative agility.

RECOMMENDATION #9: The Commission should maintain some permanent capacity with a reduced form between elections, and a one-year ramp-up in majority government situations and sufficient permanent infrastructure to organize debates in minority government situations.

RECOMMENDATION #10: The Commission should maintain a relationship with interested parties between elections to foster discussion about best practices in debate formats and production, both in Canada and other countries.

Conclusion

We warmly thank our Advisory Board as well as our partners in the Canadian Debates Production Partnership, the University of British Columbia, the University of Toronto, the Privy Council Office, and Global Affairs Canada's Summit Management Office. We delivered two debates that reached and engaged Canadians like never before. We also hope future Commissions will continue to measure and study debates in Canada and internationally: we need to learn so we can continue to improve.

These debates counted. They were key moments that helped Canadians cast informed votes. In an era of concern about our institutions and the health of democracy itself, that is a harbinger of hope.

Recommendations

Principal recommendation

We recommend the establishment of a permanent, publicly-funded entity to organize leaders' debates.

Recommendations for the next leaders' debates in Canada

RECOMMENDATION #1: The Commission should be headed by a Debates Commissioner whose appointment process involves consultation with the registered political parties represented in the House of Commons.

RECOMMENDATION #2: The Commission should organize two publicly-funded debates, one in each official language.

RECOMMENDATION #3: The Debates Commissioner should set the participation criteria for the debates; these criteria should be as objective as possible and made public before the election campaign begins.

RECOMMENDATION #4: The Commission recommends that the government encourage rather than compel leaders to participate.

RECOMMENDATION #5: The Commission should select the debates producer through a competitive process, emphasizing the need for high journalistic standards, creativity, innovation, experience, technical expertise, wide distribution, and accessibility.

RECOMMENDATION #6: The Commission should reserve the right of final approval of the format and production of the debates, while respecting journalistic independence.

RECOMMENDATION #7: The Commission should ensure the debates are available in languages other than French and English, paying special attention to Canada's Indigenous languages.

RECOMMENDATION #8: The Commission should ultimately be established through legislation (or similar mechanism) in order to prioritize greater continuity, transparency, and access to resources. Its institutional makeup should prioritize real and perceived operational independence, cost effectiveness, and administrative agility.

RECOMMENDATION #9: The Commission should maintain some permanent capacity with a reduced form between elections, and a one-year ramp-up in majority government situations and sufficient permanent infrastructure to organize debates in minority government situations.

RECOMMENDATION #10: The Commission should maintain a relationship with interested parties between elections to foster discussion about best practices in debate formats and production, both in Canada and other countries.

Appendix 1 – Leaders' Debates Commission – Order in Council P.C. 2018-1322

Whereas leaders' debates are an essential contribution to the health of Canadian democracy and are in the public interest;

Whereas it is desirable that leaders' debates reach all Canadians, including those with disabilities, those living in remote areas and those living in official language minority communities;

Whereas it is desirable that leaders' debates be effective, informative and compelling and benefit from the participation of the leaders who have the greatest likelihood of becoming Prime Minister or whose political parties have the greatest likelihood of winning seats in Parliament;

Whereas it is desirable that leaders' debates be organized using clear, open and transparent participation criteria;

Whereas it is desirable that there be a commissioner who is responsible for the organization of leaders' debates;

Whereas it is desirable that the commissioner responsible for leaders' debates have the benefit of the advice of an advisory board;

And whereas it is in the public interest that the Leaders' Debates Commission be established without delay;

Therefore, Her Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Prime Minister, establishes the Leaders' Debates Commission, in accordance with the annexed schedule.

SCHEDULE

LEADERS' DEBATES COMMISSION

Commission

1 There is established a commission, to be known as the Leaders' Debates Commission, consisting of the Debates Commissioner, the Advisory Board and the Secretariat.

2 The mandate of the Leaders' Debates Commission is to

(a) organize one leaders' debate in each official language during each general election period;

(b) ensure that the leader of each political party that meets two of the following criteria is invited to participate in the leaders' debates:

(i) at the time the general election in question is called, the party is represented in the House of Commons by a Member of Parliament who was elected as a member of that party,

(ii) the Debates Commissioner considers that the party intends to endorse candidates in at least 90% of electoral districts in the general election in question,

(iii) the party's candidates for the most recent general election received at that election at least 4% of the number of valid votes cast or, based on the recent political context, public opinion polls and previous general election results, the Debates Commissioner considers that candidates endorsed by the party have a legitimate chance to be elected in the general election in question;

(c) ensure that the leaders' debates are broadcast and otherwise made available in an accessible way to persons with disabilities;

(d) ensure that the leaders' debates reach as many Canadians as possible, including those living in remote areas and those living in official language minority communities, through a variety of media and other fora;

(e) ensure that the leaders' debates are broadcast free of charge, whether or not the broadcast is live;

(f) ensure that any reproduction of the leaders' debates is subject to only the terms and conditions that are necessary to preserve the integrity of the debates;

(g) ensure that high journalistic standards are maintained for the leaders' debates;

(h) undertake an awareness raising campaign and outreach activities to ensure that Canadians know when, where and how to access the leaders' debates; and

(i)provide advice and support in respect of other political debates related to the general election, including candidates' debates, as the Debates Commissioner considers appropriate.

3 The Leaders' Debates Commission is to

(a) conduct any necessary research or rely on any applicable research to ensure that the leaders' debates are of high quality;

(b) develop and manage constructive relationships with key opinion leaders and stakeholders;

(c) conduct its activities in a manner that does not preclude other organizations from producing or organizing leaders' debates or other political debates;

(d) ensure that the decisions regarding the organization of the leaders' debates, including those respecting participation criteria, are made publicly available in a timely manner;

(e) ensure that the leaders' responses to the invitations to participate in the leaders' debates are made publicly available before and during the debates; and

(f) conduct an evidence-based assessment of the leaders' debates that it has organized, including with respect to the number of persons to whom the debates were accessible, the number of persons who actually accessed them and the knowledge of Canadians of political parties, their leaders and their positions.

4 In fulfilling its mandate, the Leaders' Debates Commission is to be guided by the pursuit of the public interest and by the principles of independence, impartiality, credibility, democratic citizenship, civic education, inclusion and cost-effectiveness.

5 (1) The Leaders' Debates Commission is an agent of Her Majesty and, in that capacity, may enter into contracts or agreements with third parties in fulfilling its mandate.

(2) The Leaders' Debates Commission is to ensure that calls for proposals regarding the production of the leaders' debates identify clear criteria by which proposals will be evaluated, including the presentation of strategies to

(a) maximize the reach of the leaders' debates and engagement with Canadians, including those who may face barriers to voting;

(b) create momentum for and awareness of the leaders' debates before the debates take place and to sustain engagement of Canadians after the debates take place;

(c) make the leaders' debates more accessible to Canadians with disabilities, those living in remote areas and those living in official language minority communities; and

(d) ensure that the leaders' debates are reflective of high production and journalistic standards, while ensuring brand neutrality.

Debates Commissioner

6 (1) The Debates Commissioner is the director of the Leaders' Debates Commission and, in that capacity, conducts the ordinary business of the Commission and is responsible for the appointment of the members of the Secretariat.

(2) The Debates Commissioner is appointed to hold office during good behaviour, on a part-time basis, subject to removal for cause.