The 2025 Federal Leaders’ Debates: Expectations, Preferences and Reactions

Consortium on Electoral Democracy and the Canadian Election Study

Justine Bechard (University of Western Ontario)

Laura Stephenson (University of Western Ontario)

Allison Harell (Université du Québec à Montréal)

Daniel Rubenson (University of Toronto)

July 28, 2025

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Summary of Findings

- Methodology

- Findings from 2025

- Comparing Findings with 2019 and 2021

- Appendix

List of Tables and Figures

- Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents of the DC Sample

- Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of CES Respondents

- Table 3. Percentages of Respondents Expecting Debates

- Figure 1: Demographic Correlates of Expectations of Debates

- Figure 2: Expectations about Campaign Debates

- Figure 3: Importance of Televised Debates

- Figure 4: Reasons for Importance of Debates

- Figure 5: Purpose of the Election Debates

- Figure 6: Importance of the Debates for the Democratic Process

- Figure 7: Debates Protecting Democracy

- Figure 8: Debates Helping Combat the Spread of Misinformation and Disinformation

- Figure 9: Expected Outcome of Debates

- Figure 10: Ranking of Goals for a Leader’s Debate

- Figure 11: Utility of Debates for Canadian Democracy

- Figure 12: Correlates of the Perception of the Utility of Debates for Canadian Democracy

- Figure 13: Correlates of Viewership

- Figure 14: Time Spent Watching the Debates

- Figure 15: Reasons for Not Watching French-Language Debates

- Figure 16: Reasons for Not Watching English Debates

- Figure 17: Opinions about Debate Moderators Amongst Viewers

- Figure 18: Utility of Debates for Combating False Information

- Figure 19: Interest in Politics Before and After Debates

- Figure 20: Learning about Leaders through Debates, Viewers

- Figure 21: Don't Know Responses for Party Ratings

- Figure 22: Don't Know Responses for Leader Ratings

- Figure 23: Don't Know Responses for Evaluations of Party Leaders’ Intelligence

- Figure 24: Don't Know Responses for Evaluations of Party Leaders’ Leadership

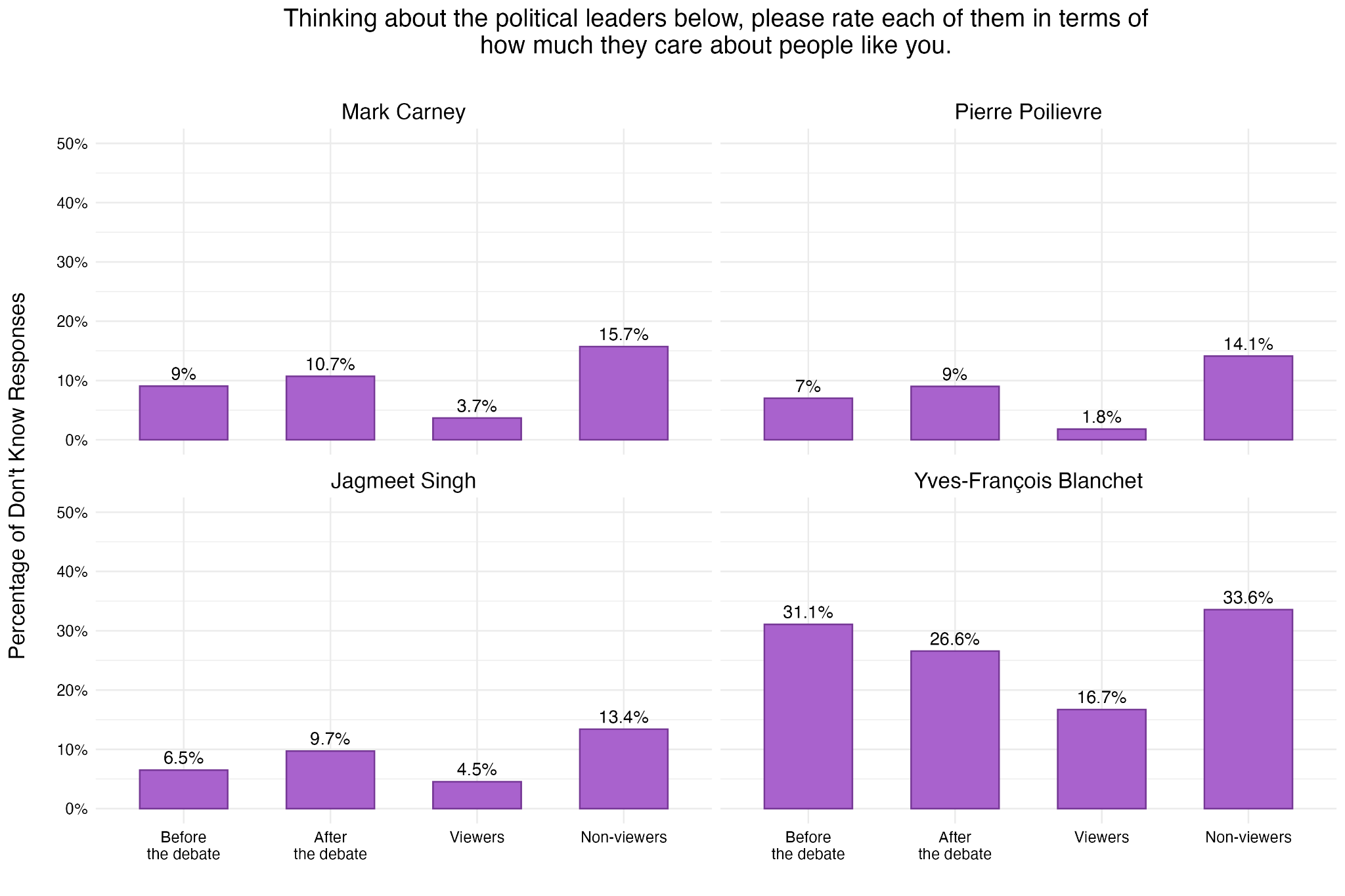

- Figure 25: Don't Know Responses for Evaluations of How Much Party Leaders Care About People

- Figure 26: Impact of Debate on Turnout and Vote Choice

- Figure 27: Vote Intent, by Viewership

- Figure 28: Reported Vote, by Viewership

- Figure 29: Views on How Canadians Watched the Debate, by Viewership

- Figure 30: Views on the Debate Exposing Canadians to New Information, by Viewership

- Figure 31: Who Benefits from Televised Debates

- Figure 32: Importance of All Leaders Participating in Debates

- Figure 33: Which Parties Should be Invited to Debates

- Figure 34: Debate Format Preference for Breadth of Participation vs. Leader Speaking Time

- Figure 35: Duty of Leader to Participate in Debates

- Figure 36: Changes in Perceptions of Leaders for Non-Participation

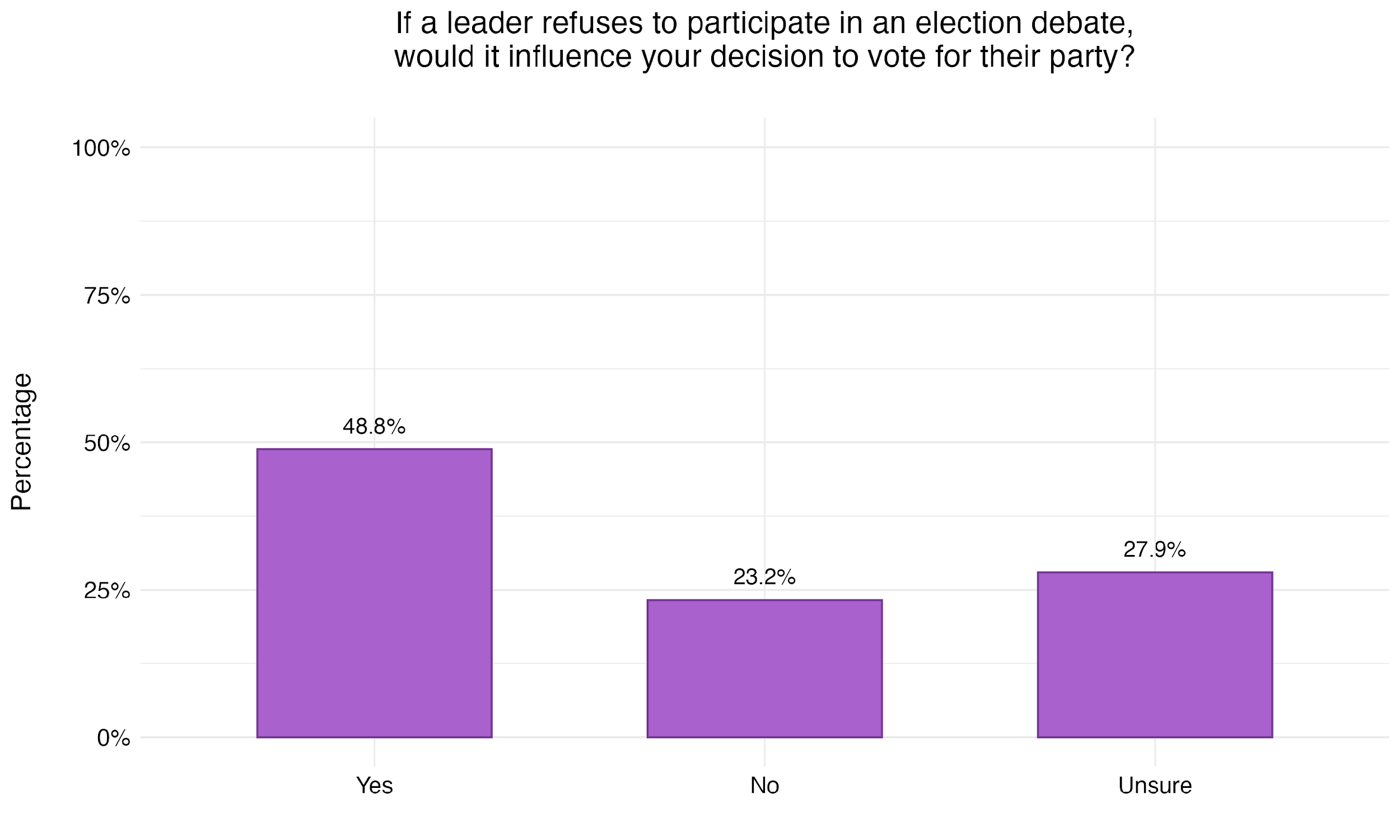

- Figure 37: Impact of Refusing to Participate in Debates on Vote Decision

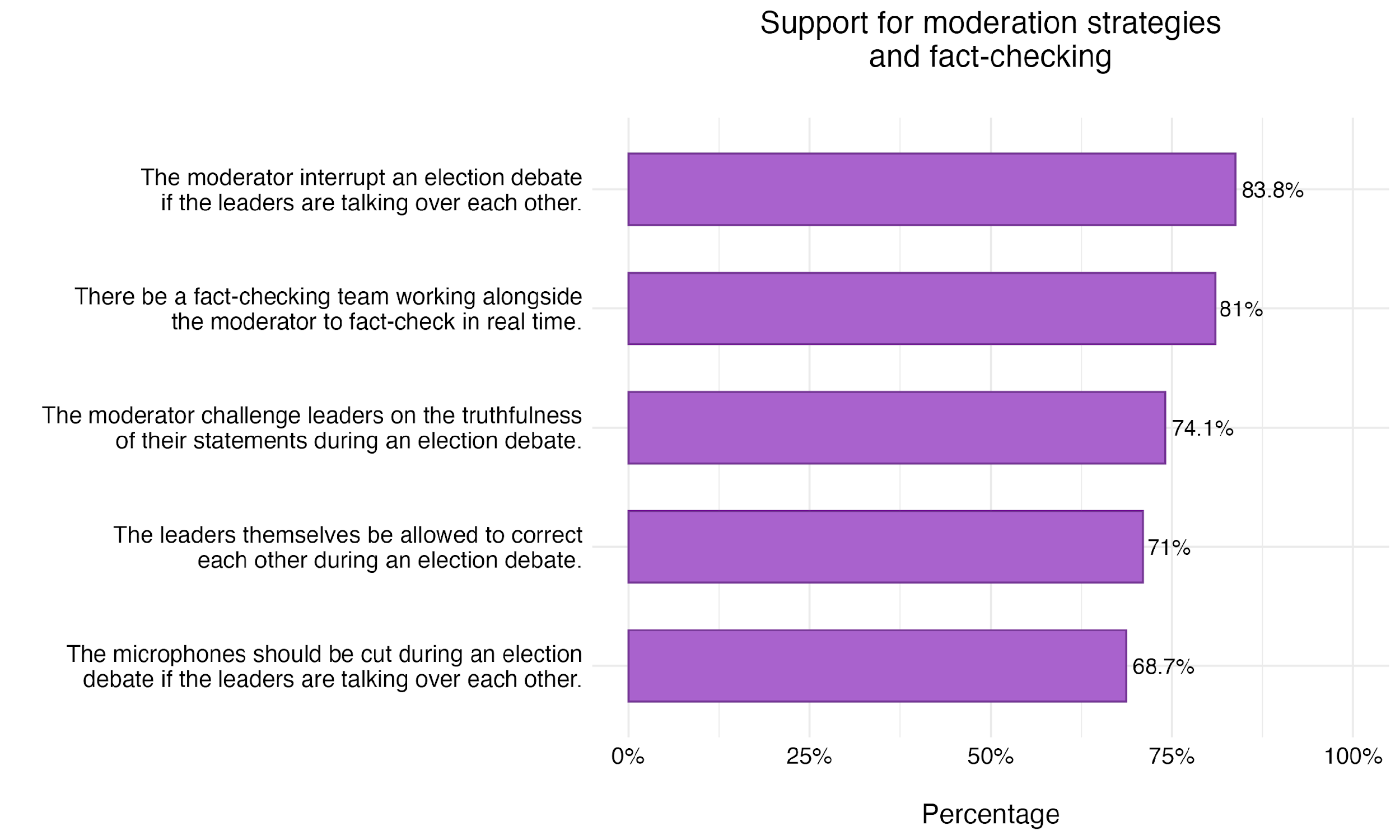

- Figure 38: Preferences Over Moderation Strategies

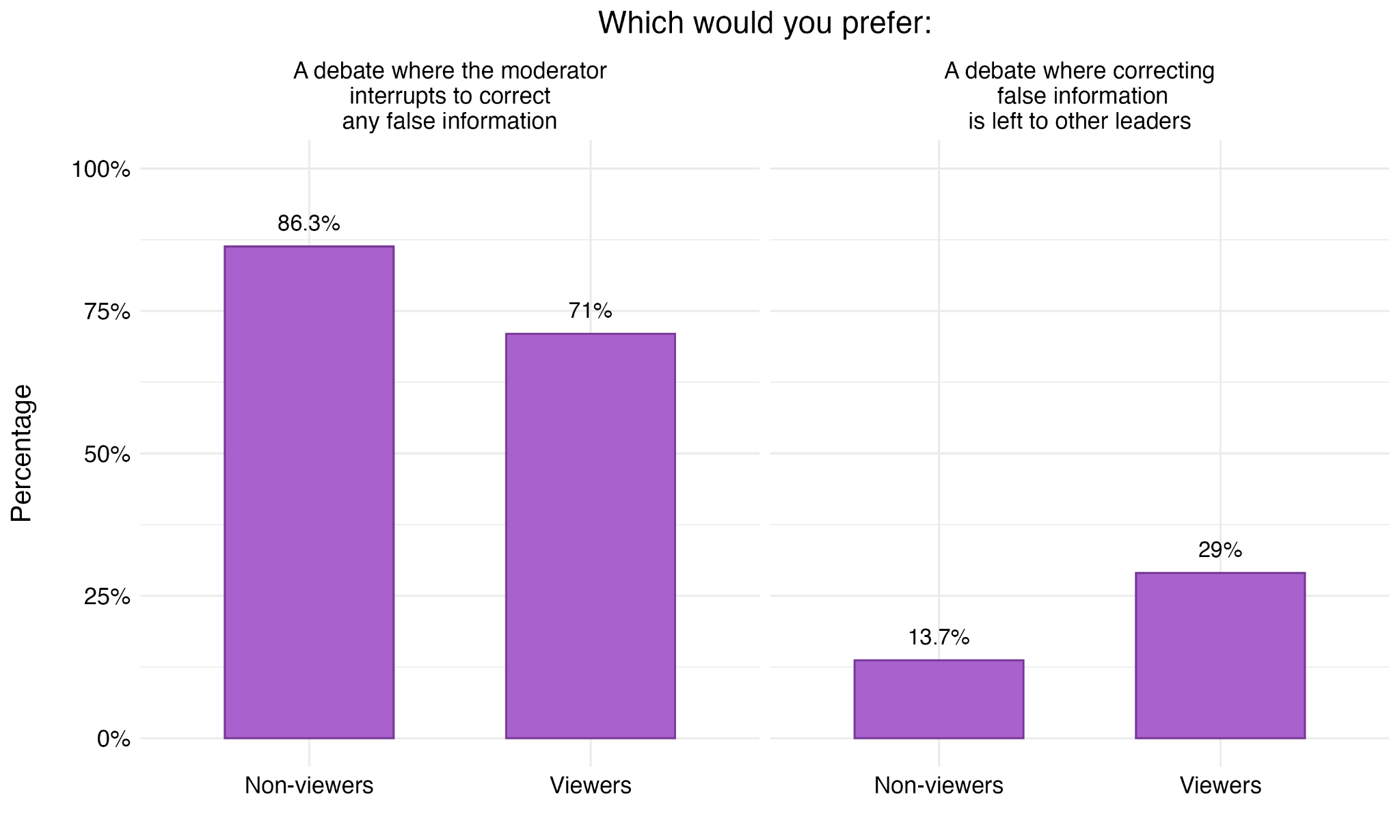

- Figure 39: Preferences over Moderator Fact-Checking Behaviour

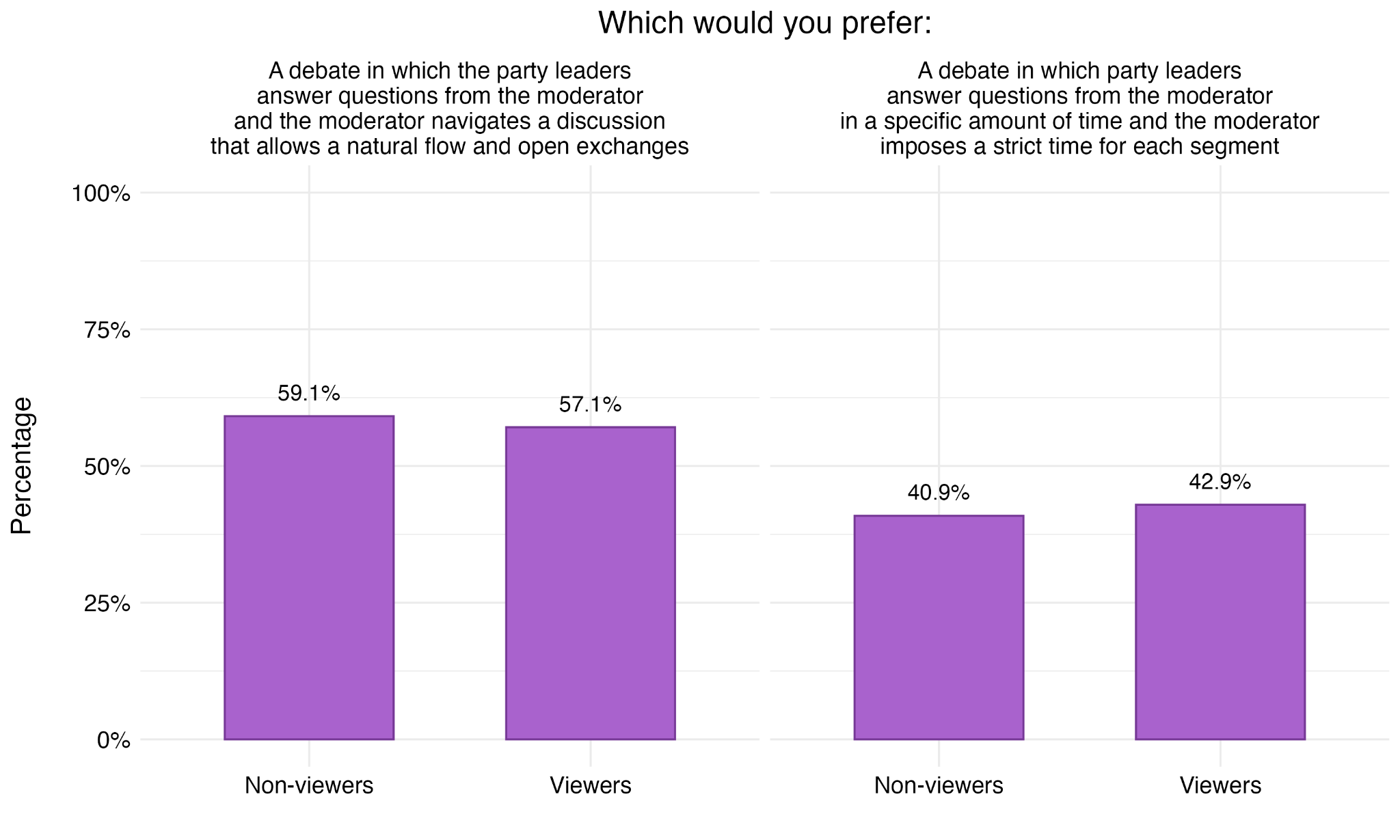

- Figure 40: Preferences over Question Format

- Figure 41: Preferences about Policy Questions

- Figure 42: Preferences about General vs. Specific Questions

- Figure 43: Preferences for Time Management

- Figure 44: Preferences Over Number of Debates

Introduction

Our research team was engaged by the Leaders’ Debate Commission (LDC) to study opinions about and reactions to the federal leaders’ debates in the 2025 election. The LDC mandate is to ensure that the debates are accessible and widely distributed; organized on the basis of clear and transparent criteria; effective, informative and compelling; and serve the public interest. Our aim with the project was to gather specific information related to the 2025 debates as well as learn preferences for future debates. We did this by conducting three different data collections: a module of questions asked of the general public in January-February 2025 in the Consortium on Electoral Democracy’s (C-Dem) Democracy Checkup (DC) survey; a module of questions asked in the campaign period survey of the Canadian Election Study (CES); and focus groups conducted during and immediately after the French and English debates.

This report can be best understood in comparison to reports written for the 2019 and 2021 elections. Wherever possible, we have replicated the analyses to allow for direct comparisons. However, unlike the previous studies, there was no panel survey design. The strength of this current study is the range of data collection efforts, including some pre-election and some at the time of the campaign (before and after the debates), and the richness of focus group information collected immediately after watching the debates.

Summary of Findings

Our results indicate that the 2025 leaders’ debates were generally well-received by the public. There is a general expectation that debates will occur before federal elections. There is also agreement that debates are important and serve to provide information about leaders, their character and their policies. The data indicate that Canadians recognize the importance of having truthful information communicated during debates and see a role for the moderators in making sure this occurs. There is also evidence that leaders are expected to attend the debates and will be penalized, personally if not in the vote outcome, for not taking part.

The analysis is less conclusive about the general evaluation of moderators. While the focus group data collected during and immediately after the debates suggested generally favourable evaluations, the survey data gathered after the debates were held shows less enthusiasm for the 2025 moderators. Across all the data, there is also evidence of a tension between wanting to have an orderly discussion such that information is clearly presented, and a debate where all major party leaders can present their cases to the public on their own terms.

There is some evidence to suggest that the learning that took place during the debates led to changes in evaluations of parties and leaders. This was clearer in self-reported learning, though we found little evidence that opinions solidified toward leaders or parties in response to debate viewership. There is also no direct evidence that vote choices were changed.

In terms of preferences for future debates and debate format, there is relative consensus that debates should include all leaders in the House of Commons, and that moderators should play a role in keeping the debate on task. Canadians generally think that two debates between party leaders were appropriate, though there was some interest in more debates or debates among MPs. While time zones and locations present challenges that were understood by our respondents, Canadians expressed less clear preferences for alternatives, though focus group participants suggested that without a live audience, debates could be presented at the same time across the country.

Methodology

Summary of Data Sources

Surveys

Pre-Election Survey Module

As part of the 2025 Democracy Checkup (DC) Wave 1, we fielded a module of questions intended to capture expectations about leaders’ debates during the next election campaign. The questions were asked of 1,004 individuals sampled from the Leger Opinion (LEO) panel. The survey was fielded between January 22, 2025 and February 2, 2025. The survey was available in French and English. Quota sampling was used to gather a sample that was representative of the Canadian population on key demographics.

Table 1 gives an overview of the demographics of the LDC sample collected in the 2025 DC, i.e. the gender, age group, language and region of the study respondents.

| Variable |

Category |

Unweighted n | Unweighted % | Weighted n | Weighted % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 499 | 49.70 | 499 | 49.70 |

| Women | 498 | 49.60 | 502 | 50.00 | |

| Non-binary or another gender | 7 | 0.70 | 3 | 0.30 | |

| Total | 1,004 | 100.00 | 1,004 | 100.00 | |

| Age | 18-34 | 238 | 23.71 | 269 | 26.79 |

| 35-54 | 309 | 30.78 | 315 | 31.37 | |

| 55+ | 457 | 45.52 | 420 | 41.83 | |

| Total | 1,004 | 100.00 | 1,004 | 100.00 | |

| First Language | English | 677 | 67.43 | 667 | 66.43 |

| French | 236 | 23.51 | 247 | 24.60 | |

| Allophone/Multilingual | 91 | 9.06 | 90 | 8.96 | |

| Total | 1,004 | 100.00 | 1,004 | 100.00 | |

| Region | Atlantic | 67 | 6.67 | 68 | 6.77 |

| British Columbia | 132 | 13.15 | 131 | 13.05 | |

| Ontario | 387 | 38.55 | 379 | 37.75 | |

| Prairies | 183 | 18.23 | 182 | 18.13 | |

| Quebec | 235 | 23.41 | 245 | 24.40 | |

| Total | 1,004 | 100.00 | 1,004 | 100.00 |

Note: Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut were excluded from the analysis.

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module

Canadian Election Study - Campaign Period Survey Module

Data were collected during the Campaign Period Survey (CPS) of the Canadian Election Study (CES) (Stephenson, Harell and Rubenson, 2025). The Canadian Election Study is the longest running survey of Canadian federal elections. The CPS was administered to a sample of respondents collected via the Leger Opinion (LEO) panel, with representative quotas for age, gender, region and language. The survey was administered in a modified rolling cross-section design, with the intent of capturing representative windows of panelists across the full campaign period. The survey was available in French and English. For LDC questions asked throughout the field period (starting March 24 and ending early on April 28), the data contains 4,300 respondents. For those asked after the debates had occurred, the sample sizes vary depending on whether they watched one or both debates. Of those assigned the LDC module, 1044 watched the English debate and 584 watched the French debate (weighted estimates).

Table 2 provides an overview of the sample characteristics and their relative weights. Due to small sample sizes, we have not included respondents who specified a gender other than woman or man in the gender analyses, and respondents from the territories in the regional analyses.

| Variable | Category | Unweighted n | Unweighted % | Weighted n | Weighted % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 2,003 | 46.58 | 2,090 | 48.60 |

| Women | 2,263 | 52.63 | 2,196 | 51.07 | |

| Non-binary or another gender | 34 | 0.79 | 14 | 0.33 | |

| Total | 4,300 | 100.00 | 4,300 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 18-34 | 1,052 | 24.47 | 1,148 | 26.70 |

| 35-54 | 1,432 | 33.30 | 1,367 | 31.79 | |

| 55+ | 1,816 | 42.23 | 1,785 | 41.51 | |

| Total | 4,300 | 100.00 | 4,300 | 100.0 | |

| First Language |

English | 2,854 | 66.37 | 2,671 | 62.12 |

| French | 568 | 13.21 | 804 | 18.70 | |

| Allophone/Multilingual | 878 | 20.42 | 825 | 19.19 | |

| Total | 4,300 | 100.00 | 4,300 | 100.0 | |

| Regions | Atlantic | 287 | 6.67 | 289 | 6.72 |

| British Columbia | 680 | 15.81 | 598 | 13.91 | |

| Ontario | 1,807 | 42.02 | 1,663 | 38.67 | |

| Prairies | 848 | 19.72 | 758 | 17.63 | |

| Quebec | 678 | 15.77 | 991 | 23.05 | |

| Total | 4,300 | 100.00 | 4,300 | 100.0 |

Note: Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut are excluded from the analysis.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey, LDC Module

Survey Variables

The DC and CES survey modules included custom-designed questions aimed at assessing Canadians’ experiences with and attitudes about the debates. A full list of the survey items are provided in Appendices A and B. Missing responses were excluded from analyses. Similarly, respondents who answered “I don't know/Prefer not to answer” were not included in the calculation of descriptive statistics and regression analyses. All demographic questions were recoded as indicated in Appendix C.

Survey Weights

Weights were calculated for the DC and CES survey modules to improve representativeness. For the DC module, the weights were calculated using an iterative "raking'' process, as provided by the ipfraking command in STATA15. Marginal values were successively weighted according to province (with Quebec divided by language), as well as gender and age group, based on the 2021 Canadian Census. A maximum of 200 iterations were completed. For the CES module, the weights were also calculated using an iterative "raking'' process, as provided by the ipfraking command in STATA15. Marginal values were successively weighted according to province, as well as gender, age group, and education level. All population data were taken from the 2021 Canadian census. A maximum of 200 iterations were completed. Note that respondents from the Territories do not have weights, as they were not included in the sampling frame, because data collection in the Territories is too sparse to be representative. For this reason, they were also excluded from the analyses.

All of the analyses presented in this report are weighted, except if they present the opinions of debate viewers or non-viewers separately. Because we do not have reliable expectations for the demographic profile of viewers, these analyses are unweighted.

Focus Groups

Four semi-structured focus groups were organized by C-Dem on behalf of the LDC for the French and English federal leaders' debates held on April 16 and 17, 2025, respectively. Two focus groups were held on April 16 in French (8 participants per group) and two were held on April 17 in English (7 and 8 participants, respectively). The participants were recruited by CRC Research, and focus groups were moderated by trained graduate students from the University of Western Ontario. To be eligible, participants had to be Canadian citizens and 18 years of age or older. Participants also had to be available, have access to technological devices that would enable their participation in an online focus group, and have not taken part in a recent market research session in the last six months or one related to the topic, or be scheduled to take part in such a study. The focus group protocol is included as Appendix D.

Participation in the focus groups consisted of watching the two-hour debate live while on Zoom, followed by a one-hour discussion. During the debate, the facilitators wrote questions in the chat section of the Zoom meeting to keep the group engaged and to elicit immediate reactions to debate content. Responses were recorded by saving the text of the chat. Following the debate, the focus group discussion was organized into four main sections, touching on key themes for understanding how the debate was perceived and experienced by the participants. In the first section of the discussion, the facilitators gave participants time to share their overall impressions. This was followed by a discussion of the moderator's performance and role in the debate. The third, more exhaustive section looked at the format of the debate in terms of what they liked and disliked generally, who took part in the debate, criteria for determining who gets invited, fact-checking, the location and time of the event, and any other suggestions respondents had. To conclude the discussion, respondents were asked whether they would like to see more debates in each federal election and to what extent it would be interesting to consider debates between members of parliament or riding candidates.

To analyze the focus groups, we first created anonymized transcripts of the four sessions, including both the chat discussion and the focus group that followed the debate. This was done in two steps. First, draft versions were generated using the Microsoft Word dictation feature to transcribe the audio recordings. Each recording was then manually reviewed. A code was assigned to each participant to indicate individual speakers throughout the documents, and any mention of first names by participants during the discussion was replaced with the corresponding identification. To analyze the themes expressed during each section of questions, we used NVivo software to hand-code the transcripts using the coding frame (see Appendix E). The coding was done at the sentence-level, which means that whole sentences are coded as part of a theme rather than only the relevant parts. Facilitator questions were occasionally included in the coding when doing so provided more context for interpreting the participant's response. Generally, assigning an entire response or paragraph to a single thematic code was avoided if only certain parts were directly relevant to that theme.

Findings from 2025

Expectations and Objectives about Leaders’ Debates

Overall Expectations and Across Demographic Groups

In the DC, we asked “Do you expect that there will be leaders’ debates in advance of the next federal election?”. Overall, about 87.1% of respondents answered that they expected debates to be held. A demographic breakdown is provided in Table 1. Expectations were highest among those aged 35-54, who were not disabled, of European ancestry, men, not part of an official language minority, and from British Columbia.

| Variable | Category | Yes (%) | No (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18-34 | 84.9 | 15.1 |

| 35-54 | 88.3 | 11.7 | |

| 55 + | 87.6 | 12.4 | |

| Disability | Disabled | 81.3 | 18.7 |

| Not disabled | 87.3 | 12.7 | |

| Ethnicity/ancestry | European | 88.0 | 12.0 |

| Indigenous | 78.4 | 21.6 | |

| Non-European | 82.5 | 17.5 | |

| More than 1 ethnicity | 87.4 | 12.6 | |

| Gender | Men | 88.2 | 11.8 |

| Women | 86.0 | 14.0 | |

| Official language minority | Official language minority | 84.2 | 15.8 |

| Not an official language minority | 87.2 | 12.8 | |

| Region | Ontario | 86.5 | 13.5 |

| Atlantic | 83.5 | 16.5 | |

| British Columbia | 90.0 | 10.0 | |

| Prairies | 87.9 | 12.1 | |

| Quebec | 87.0 | 13.0 |

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

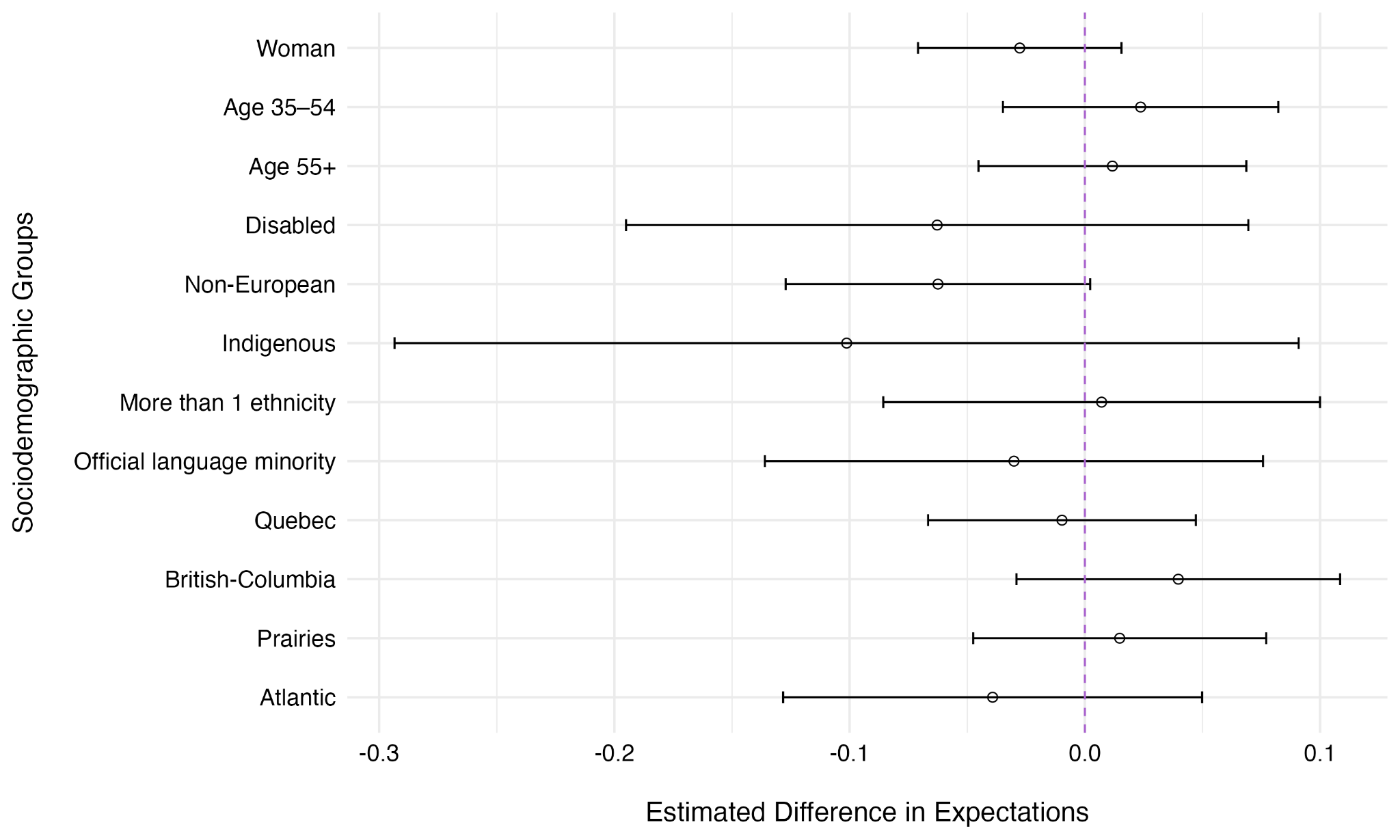

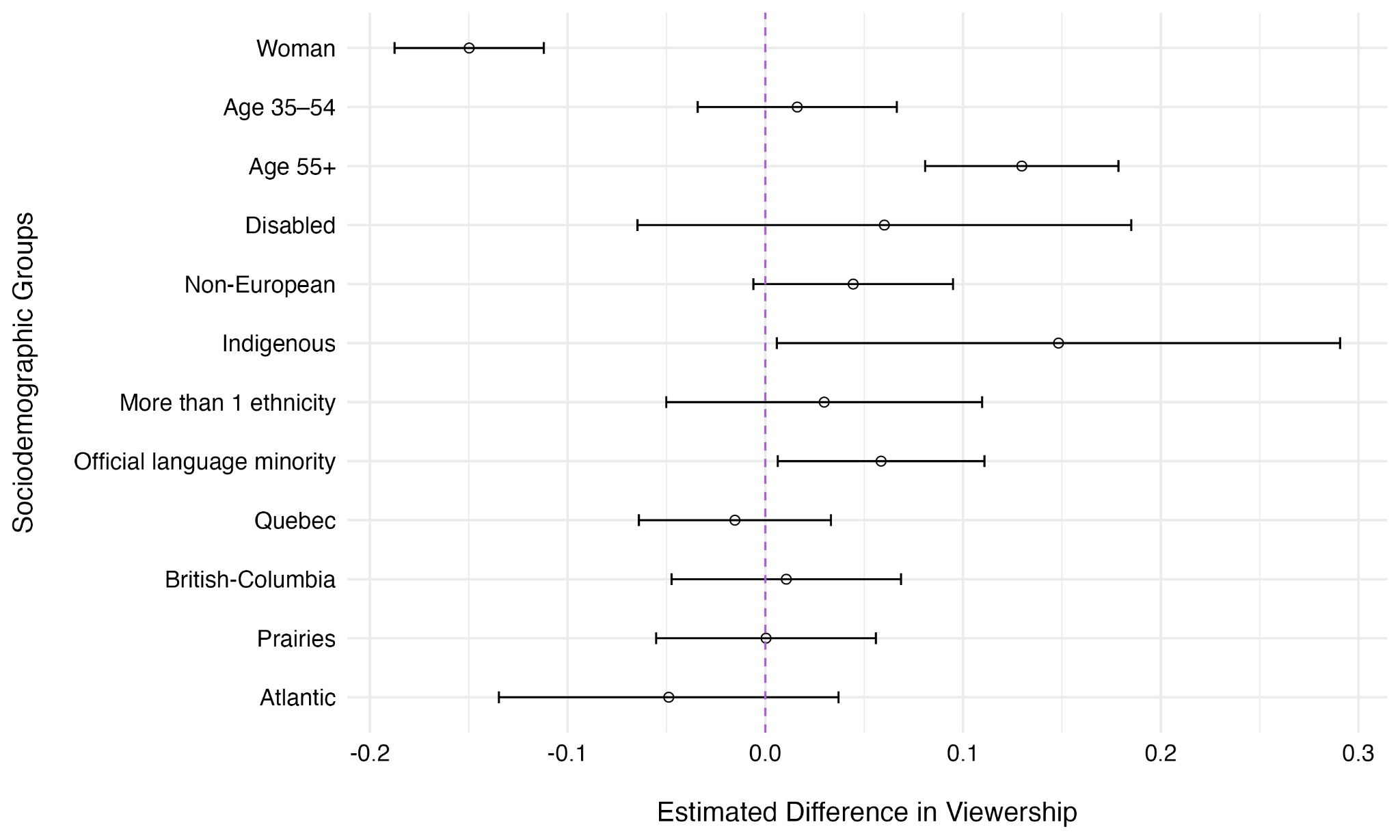

We can also use this question in a regression analysis to understand if there are significant trends in who is more likely to expect, and therefore be aware, of the debates. We tested the relevance of a number of demographics – age, gender, ethnicity, language and disability. Estimates that overlap the 0 point indicate that there is no evidence of a difference from the reference category in likelihood of reporting expecting debates. As is clear in Figure 1, no demographics emerged as significant predictors of debate awareness, meaning that there is no systematic bias such that one group was more likely to expect the debates to occur compared to than others.

Note: Points represent estimates from a weighted linear regression model with 95% confidence intervals. The dependent variable is binary (1 if the participant responded they were expecting leaders’ debates in advance of the federal election; 0 otherwise). The reference category for age is 18-24. Disability is measured by participant self-identification; the reference category is no disability. The categories of ethnicity/ancestry presented are Indigenous, More than 1 ethnicity and Non-European, with European as the reference category. For official language minority, we consider both participants who learned French as their first language, still understand it, and live outside Quebec; or who learned English as their first language, still understand it, and live in Quebec. Not being an official language minority is the reference category. For gender, being a woman is coded as 1 and a man as 0 (the reference category). The variables for the different regions of Canada use Ontario as the reference category.

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

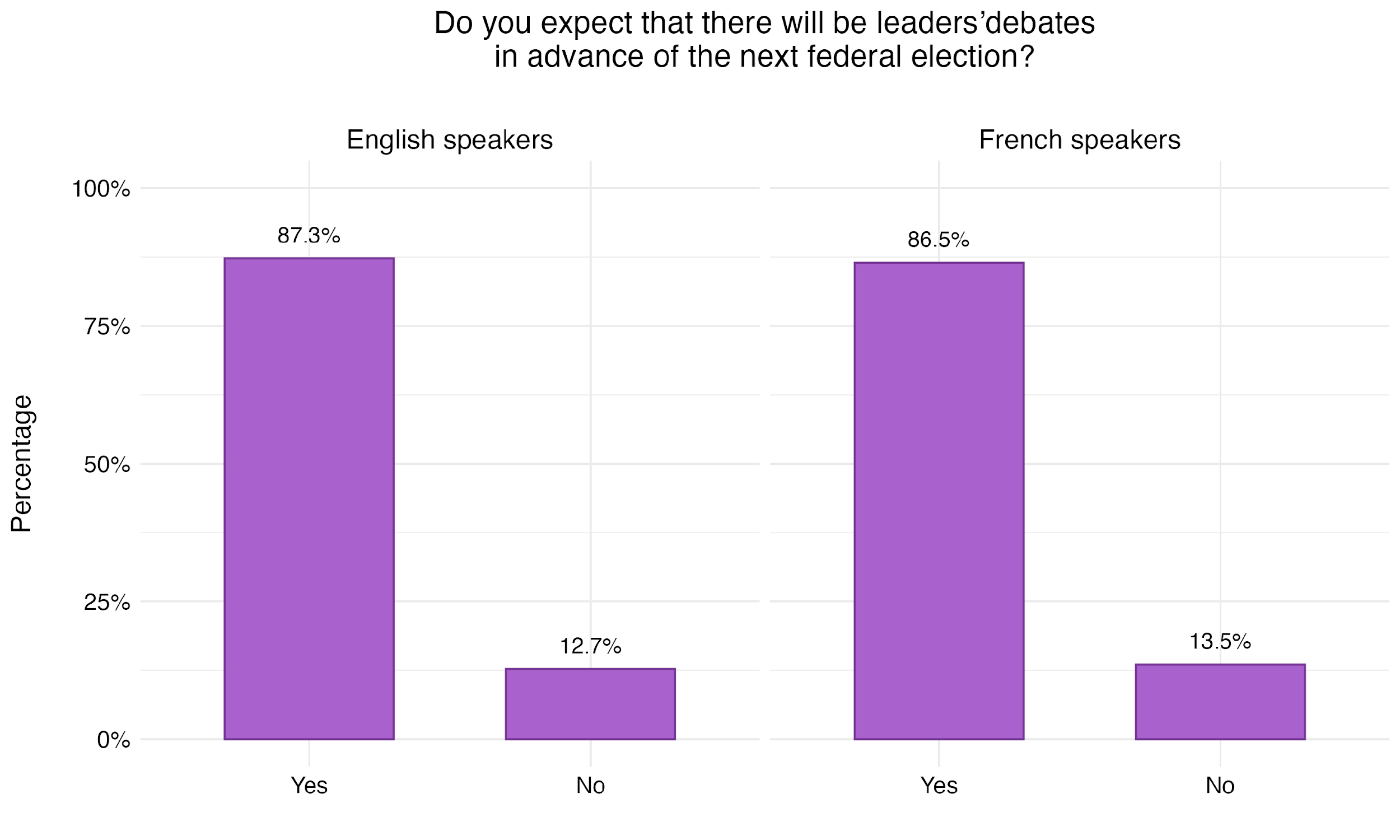

There is also little difference in expectations by language. Overwhelmingly, both English (87.3%) and French (86.5%) speakers indicated that they expected a leaders’ debate to occur before the next federal election (see Figure 2).

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

Importance and Objectives of Leaders’ Debates

In both the DC and CES, questions were included to probe the role of debates in Canadian democracy. We first consider evidence from the DC, which was gathered prior to the election call.

Pre-Election Attitudes

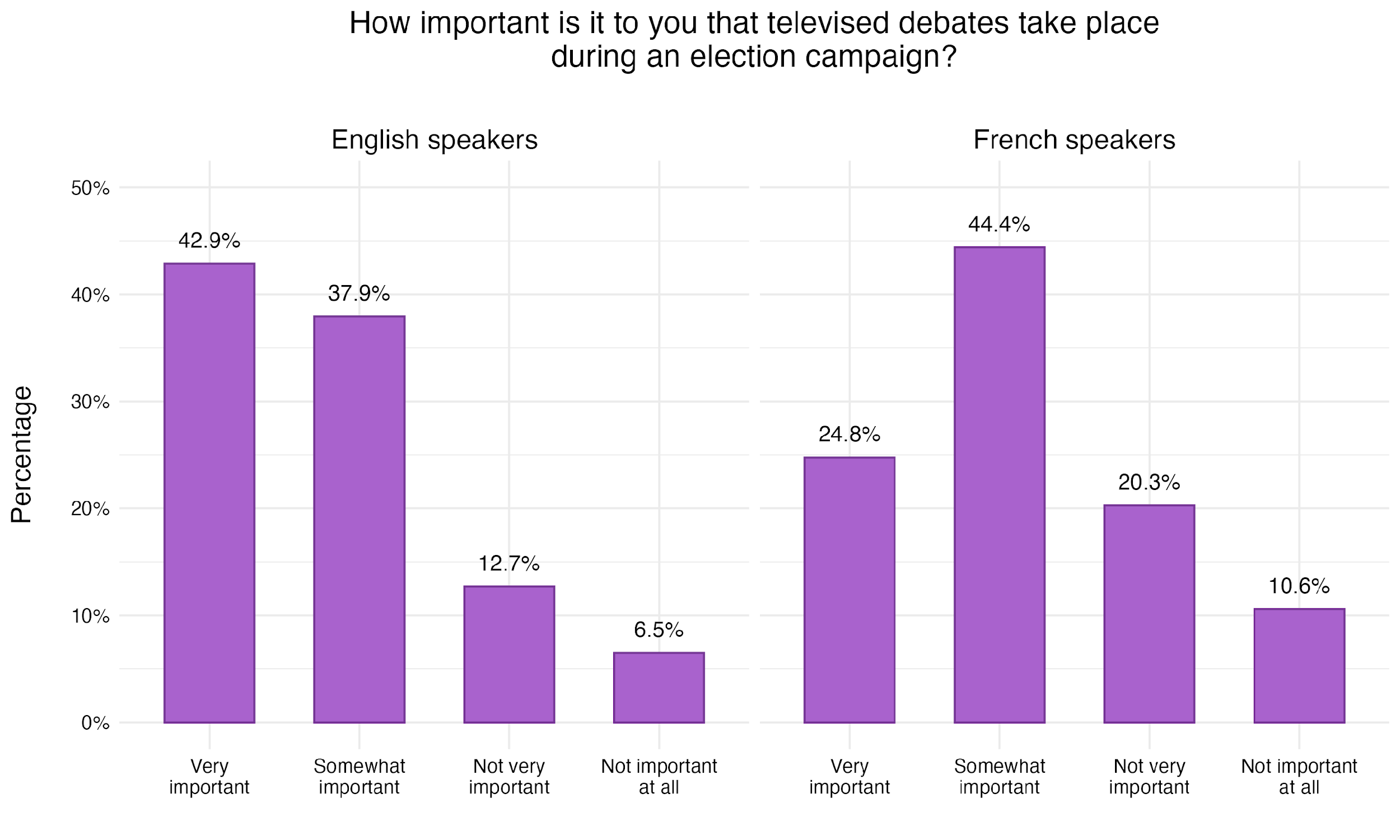

Before the election call, respondents indicated that they thought having debates was important, although the degree of importance varied by language: about 43% of English speakers indicated the debates were “very important” compared to about 25% of French speakers, but about 44% of French speakers indicated “somewhat important” compared to 38% of English speakers (see Figure 3). Overall, having debates was considered somewhat or very important by 81% and 69% of the two populations, respectively. French speakers overall consider having televised debates less important.

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

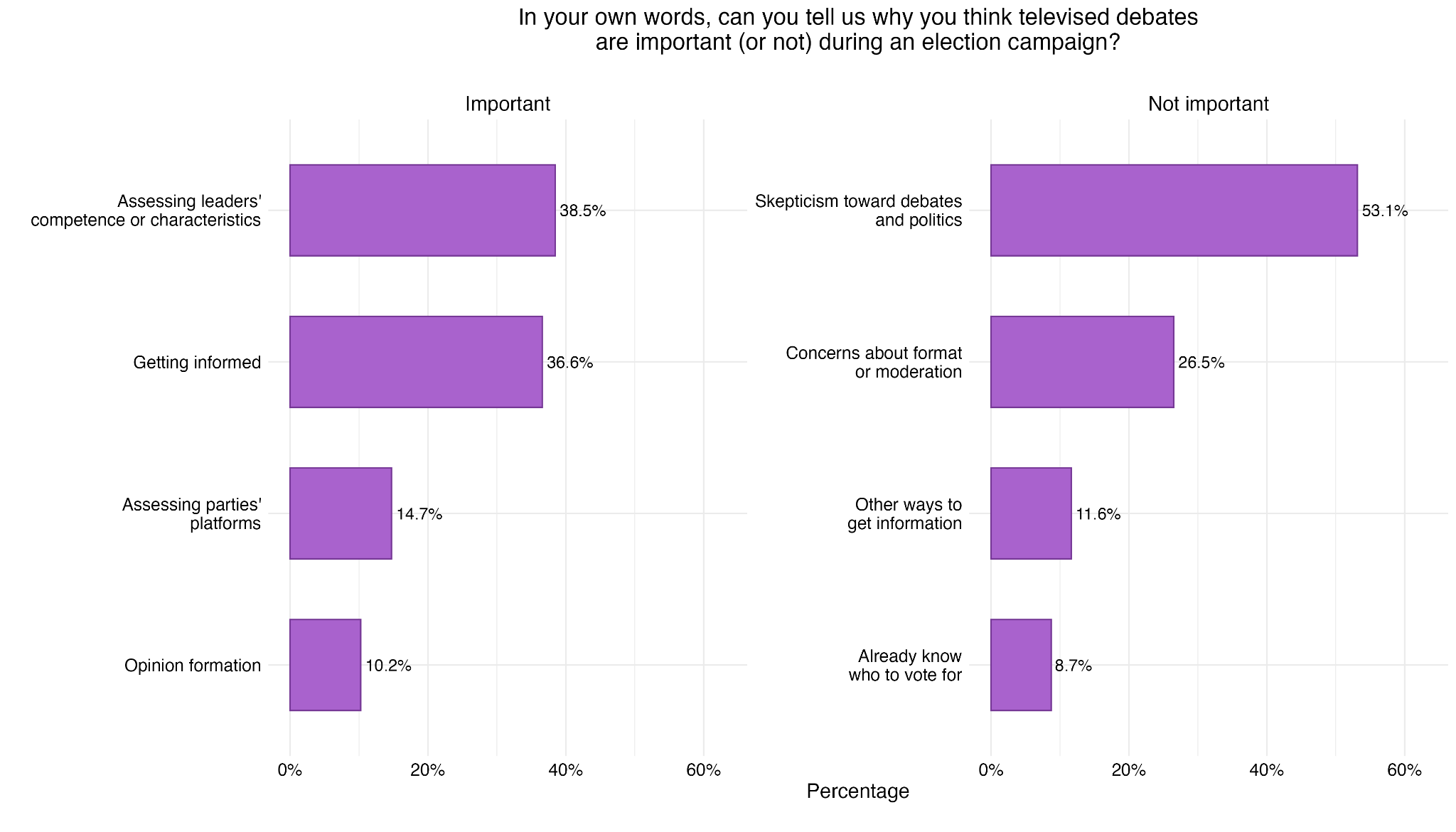

We also probed the reasons for importance perceptions with an open-ended question. Respondents were asked to indicate why they thought debates were very important, somewhat important, not very important or not important at all, depending on what they had previously answered. In Figure 4 we report a summary of responses based on a qualitative categorization of answers. The darker bars indicate responses when the individual indicated debates were important (somewhat or very). The lighter responses are from those who indicated debates are not very or not at all important. Of the entire sample, it is clear that debates are seen as important for informing voters and giving them a chance to assess the leaders’ characteristics. For those who did not see debates as important, responses tend to be more cynical or suggest that people did not find debates to be useful sources of information.

Note: The percentages are based on a qualitative, hand-coded categorization of answers to the question (n=936).

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

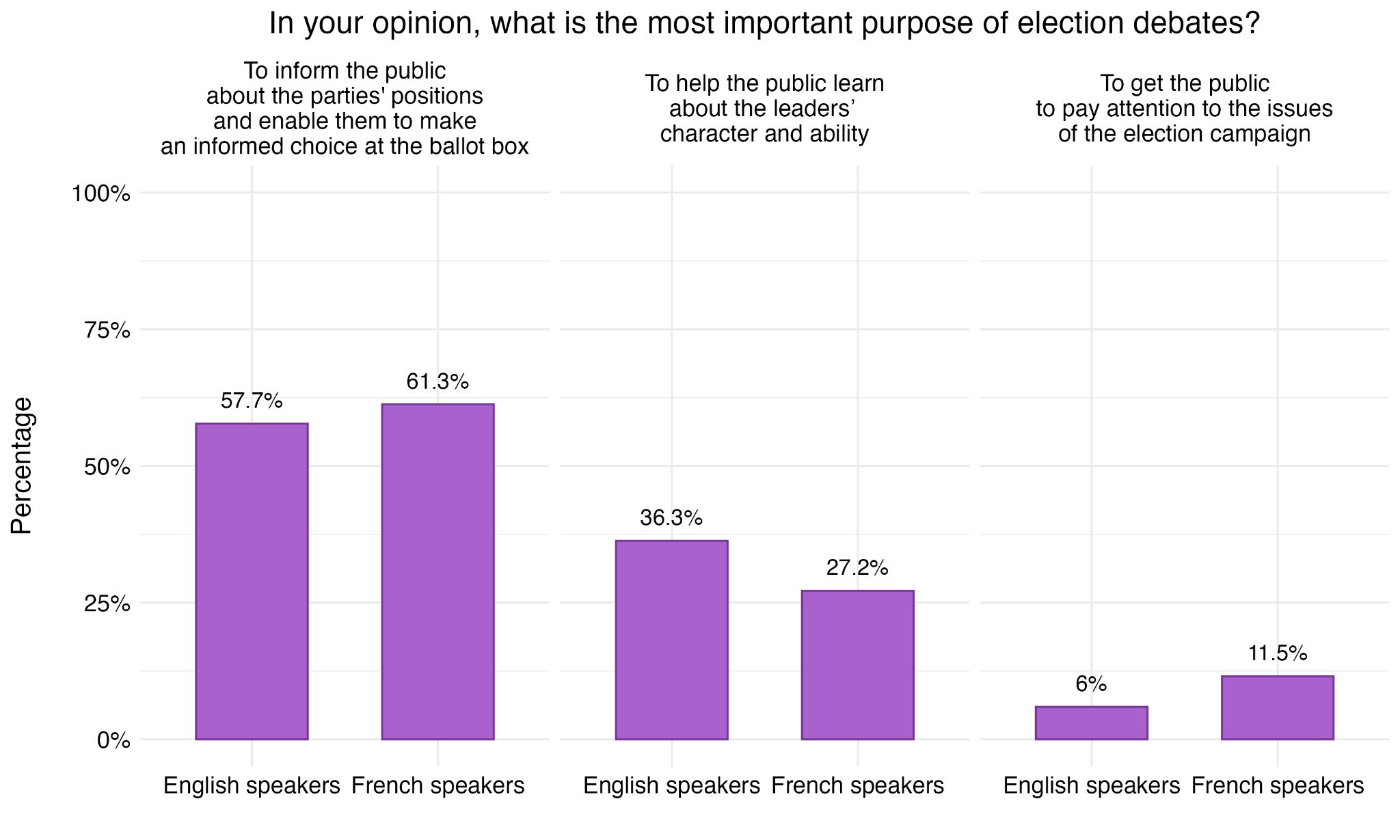

Figure 5 shows that a majority of both English and French speakers think debates are intended to inform the public about party positions and help them to make an informed vote choice. More than a quarter of Canadians also agreed that debates are intended to provide information about leaders’ character and abilities. More English-speakers agreed with this goal. Finally, a small number agreed that debates were intended to get the public to pay attention to campaign issues, but there was a divide such that more French-speakers (11.5%) agreed compared to only 6% of English speakers.

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted).

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

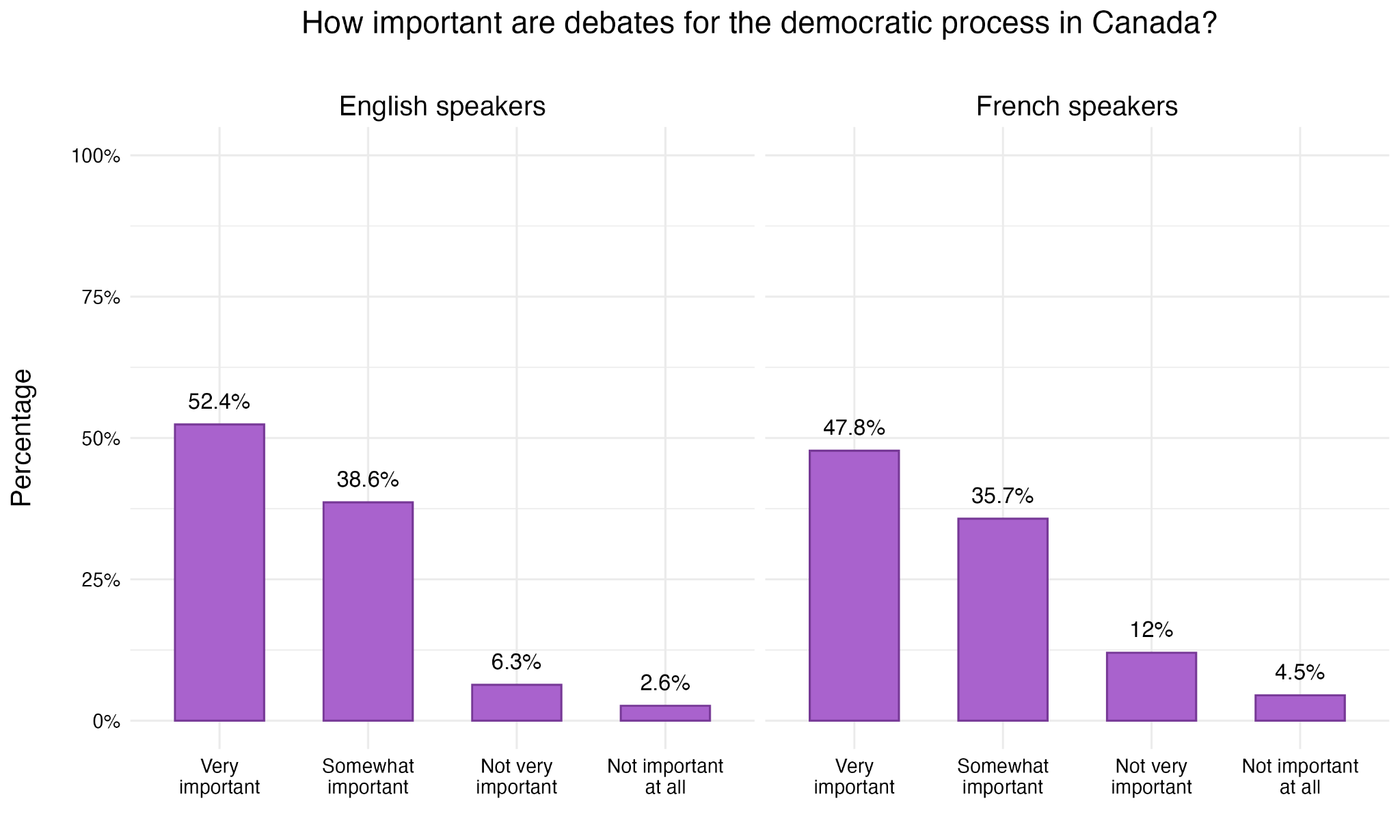

We also gathered information about the perceived role of debates in Canadian democracy. Figure 6 shows how important respondents felt the debates were for democracy in Canada. Among English speakers, 91% said debates are somewhat or very important. Among French speakers, the value is 83.5%, which is lower but still clearly a majority opinion.

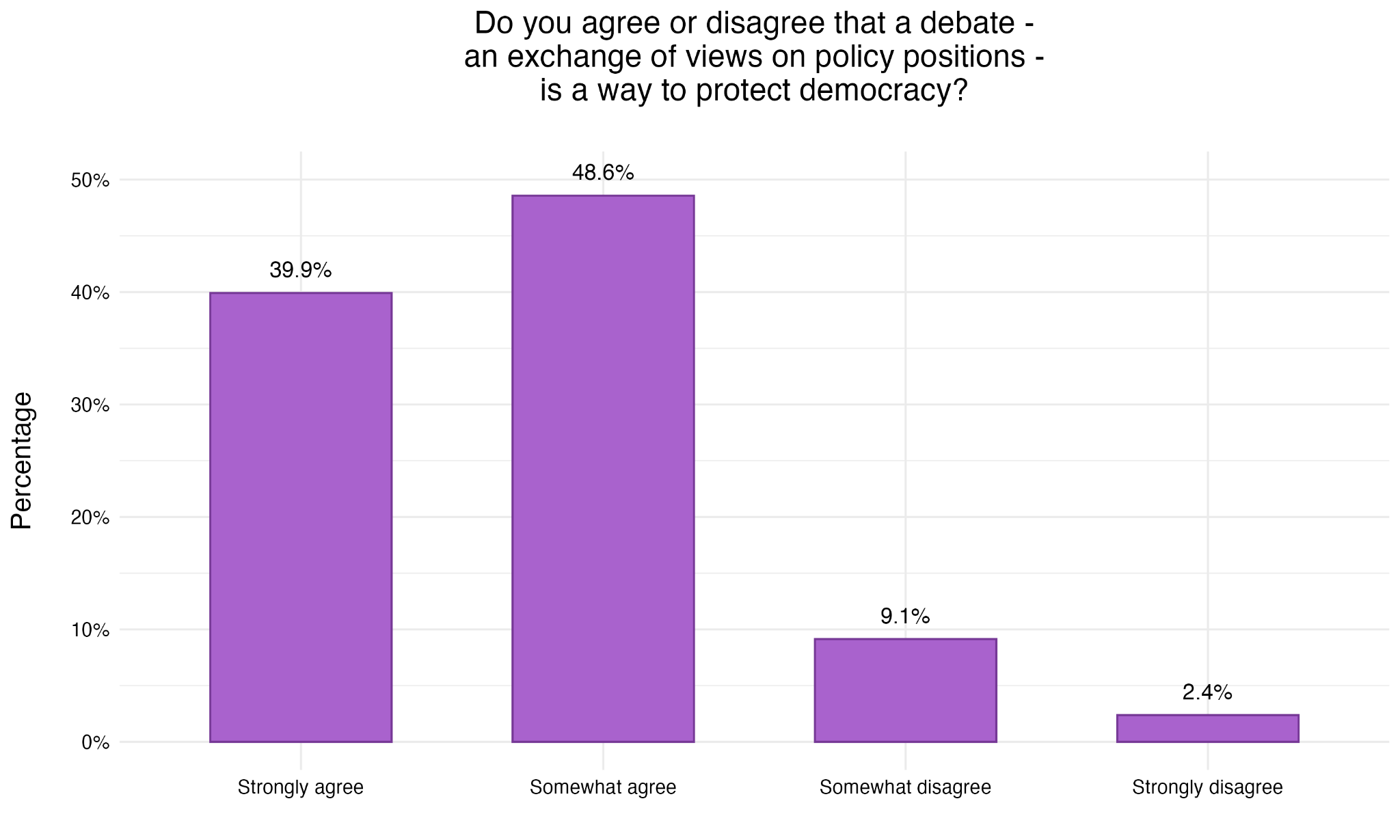

Responses about the value of debates for protecting democracy reinforce this view (see Figure 7). Almost 89% of respondents indicated agreement.

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

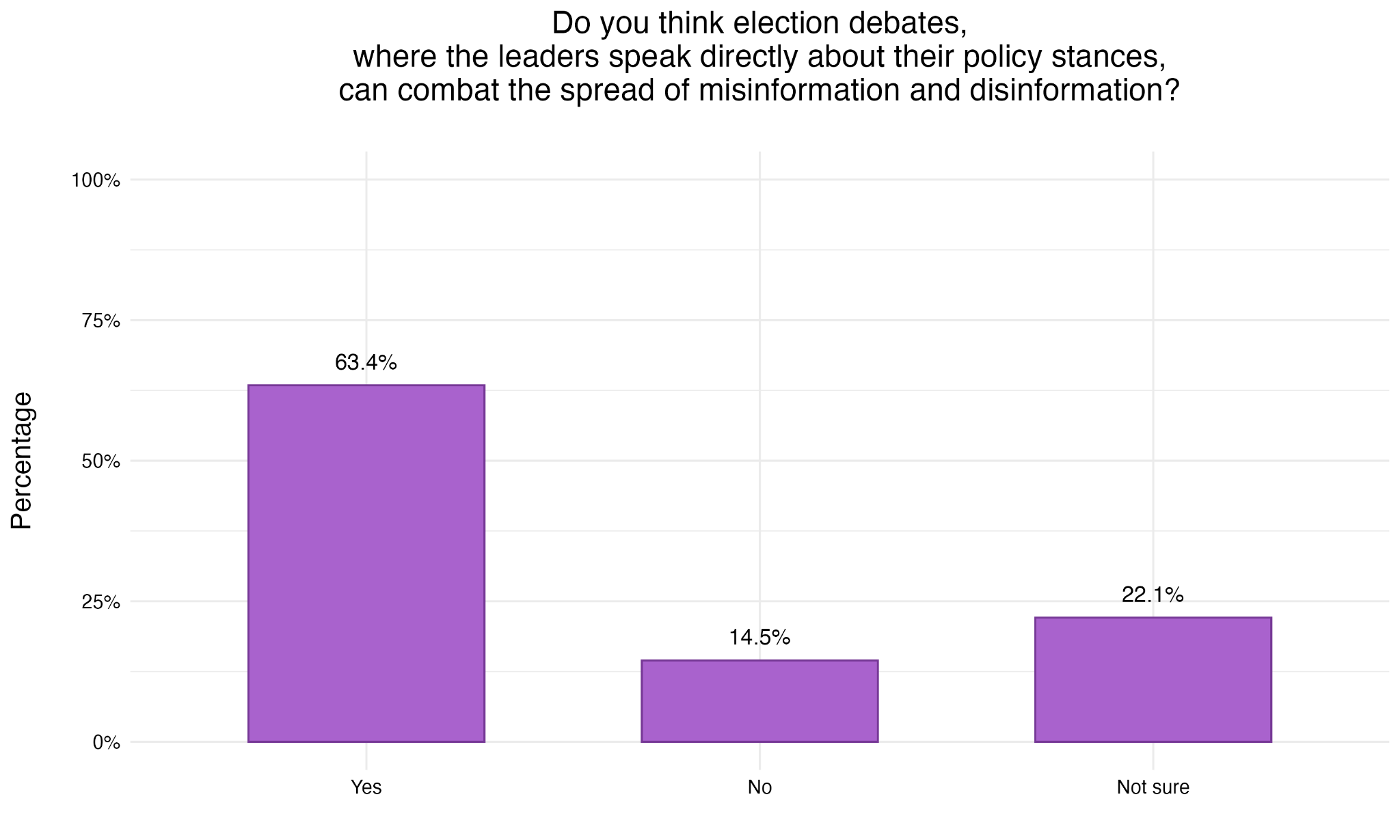

In addition, respondents also indicated that they thought debates have a role to play in combating misinformation and disinformation (63%, Figure 8). Only 14.5% disagreed, and 22% said they were unsure. In today’s society, where citizens are bombarded with so much information and the accuracy of that information can be suspect, this is an important consideration. Hearing information directly from the leaders in an organized event must be seen as a legitimate and valuable source of accurate information.

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

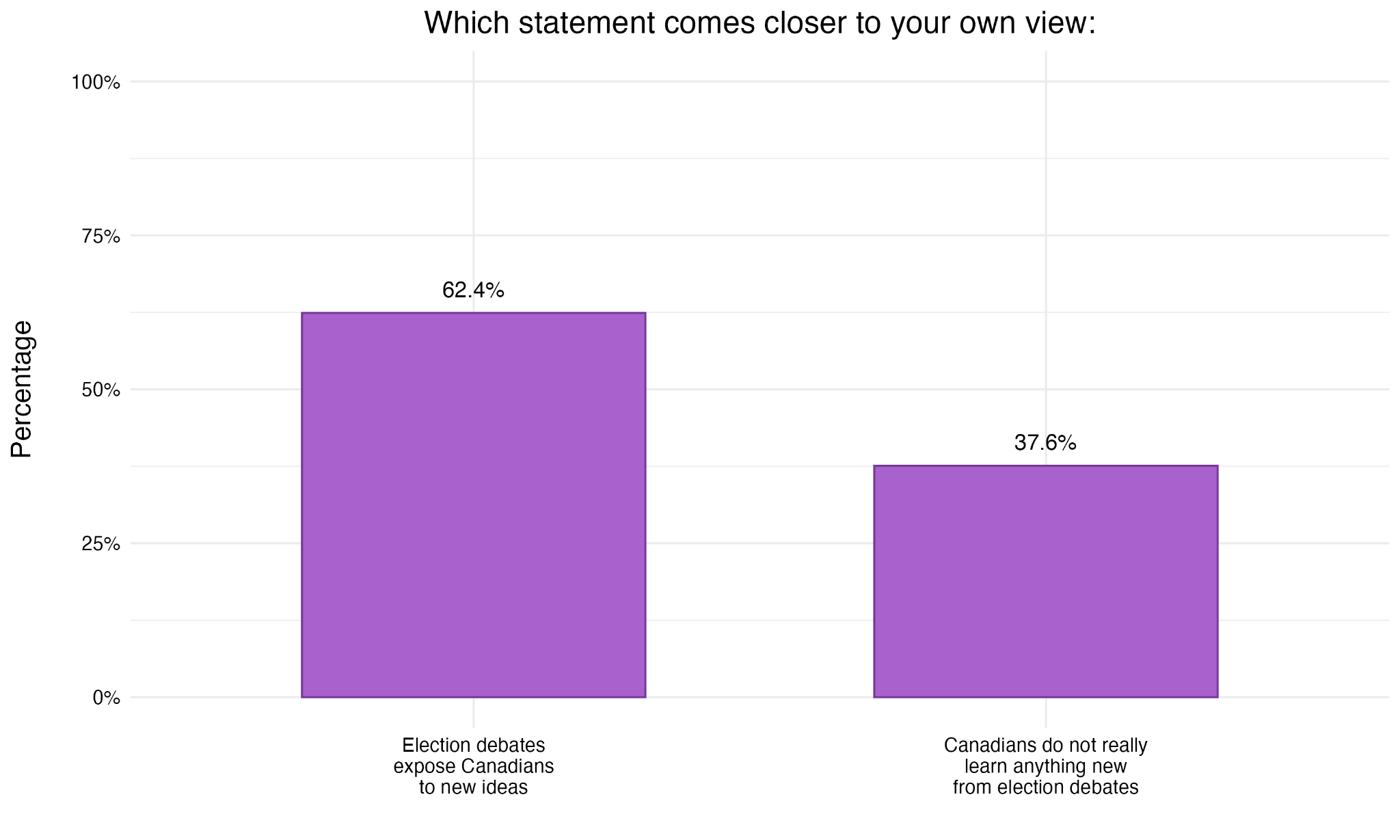

Finally, we asked about the expectation of what would occur among viewers due to watching the debates. Figure 9 shows that, when asked to choose between two statements (“Election debates expose Canadians to new ideas” and “Canadians do not really learn anything new from election debates”), a majority (62.4%) agreed that debates provide exposure to new ideas.

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

Election Campaign Attitudes

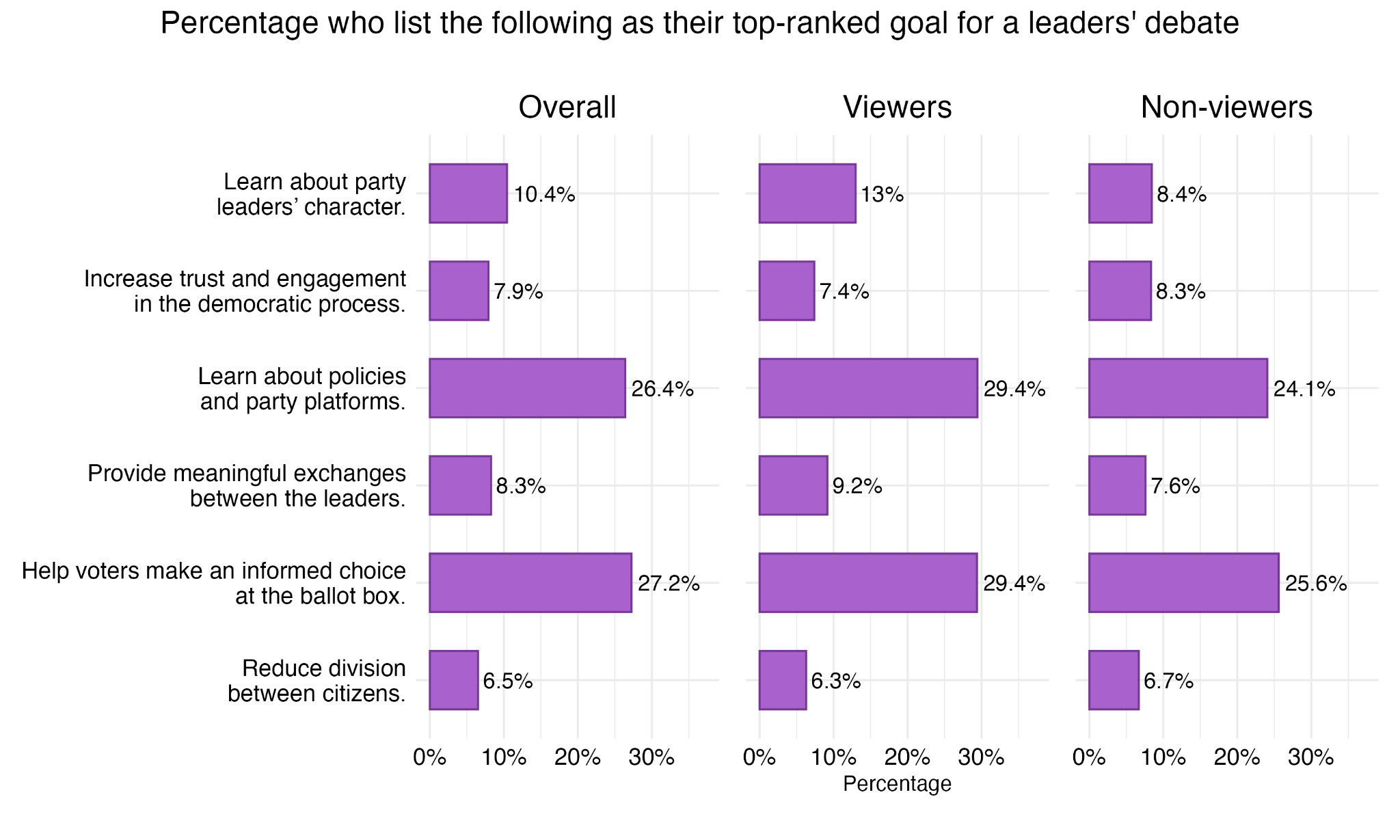

Turning now to the data gathered during the campaign in the CES, we asked respondents to rank specific goals of debates in terms of their importance as follows: “Here is a list of possible goals for a leaders’ debate. Please rank the top 3 goals personally by entering 1, 2 or 3 into the relevant textbox, with 1 being the most important, 2 being the second most important and 3 being the third most important”. Figure 10 shows the distribution of rankings across the items, for the whole sample of individuals who took the survey before the debates were held and then for viewers and non-viewers surveyed after the debates. The items ranked highest do not vary between viewers and non-viewers - learning about policies and party platforms, and helping voters to make an informed choice. These are clearly the goals of holding that are held amongst Canadians. In keeping with other findings, learning about party leaders’ character was a common response ranked second or third in importance (not shown).

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey, LDC Module (Weighted)

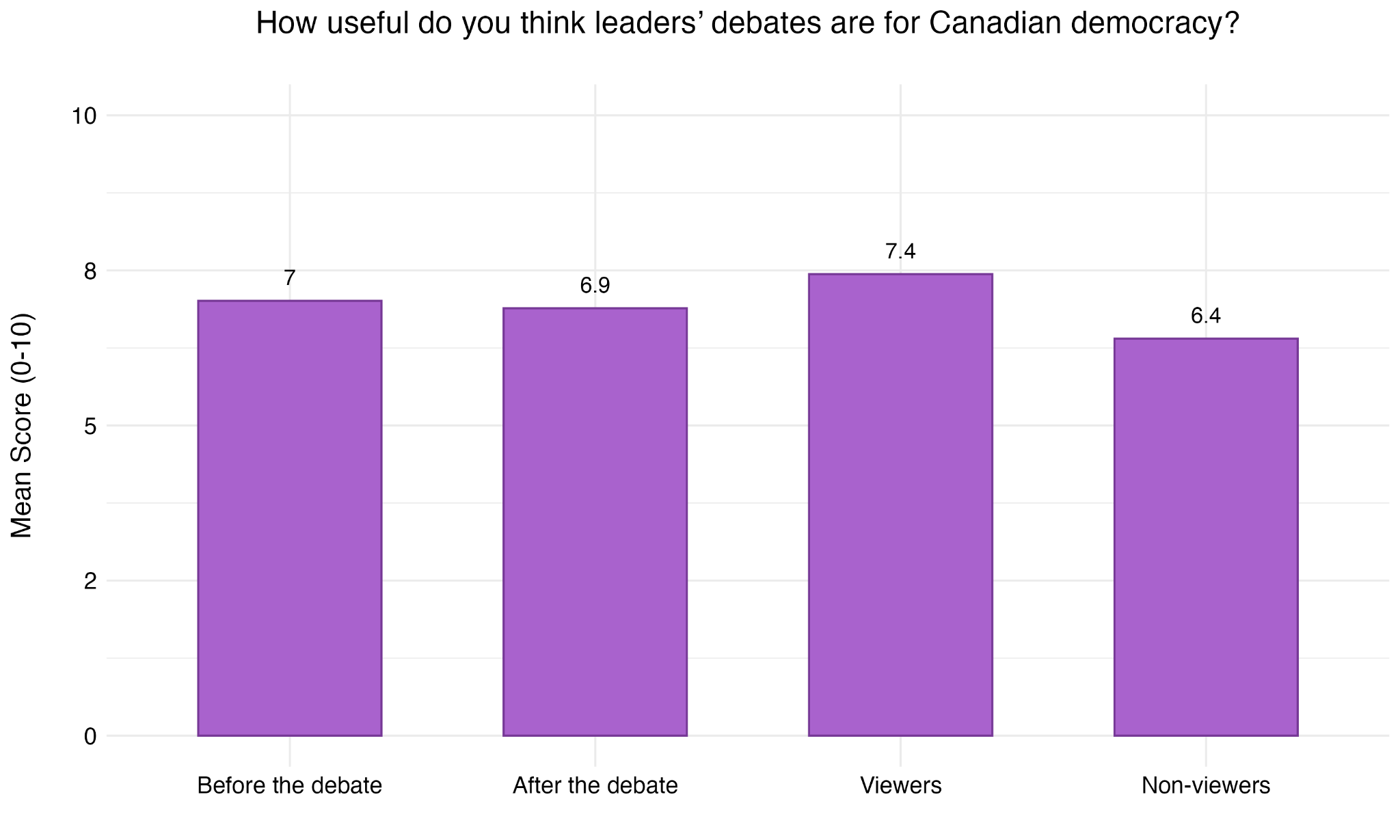

We also asked respondents in the CES to indicate their overall rating of how useful debates are for Canadian democracy on a scale of 0-10. In general, Canadians were positive about their usefulness. The overall average is 6.9, suggesting that debates are generally valued in Canadian society. Figure 11 breaks this down by pre- and post-debate attitudes, as well as among viewers and non-viewers (both post-debate). Post-debate attitudes about debate usefulness are not significantly different than pre-debate attitudes, suggesting that the experience of the debates did not help (or hurt) Canadians’ views about their usefulness. However, we do find a significant difference between those who watched the debate (average = 7.4) and those who did not (average = 6.4). While both are generally positive, viewers were more so.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey, LDC Module

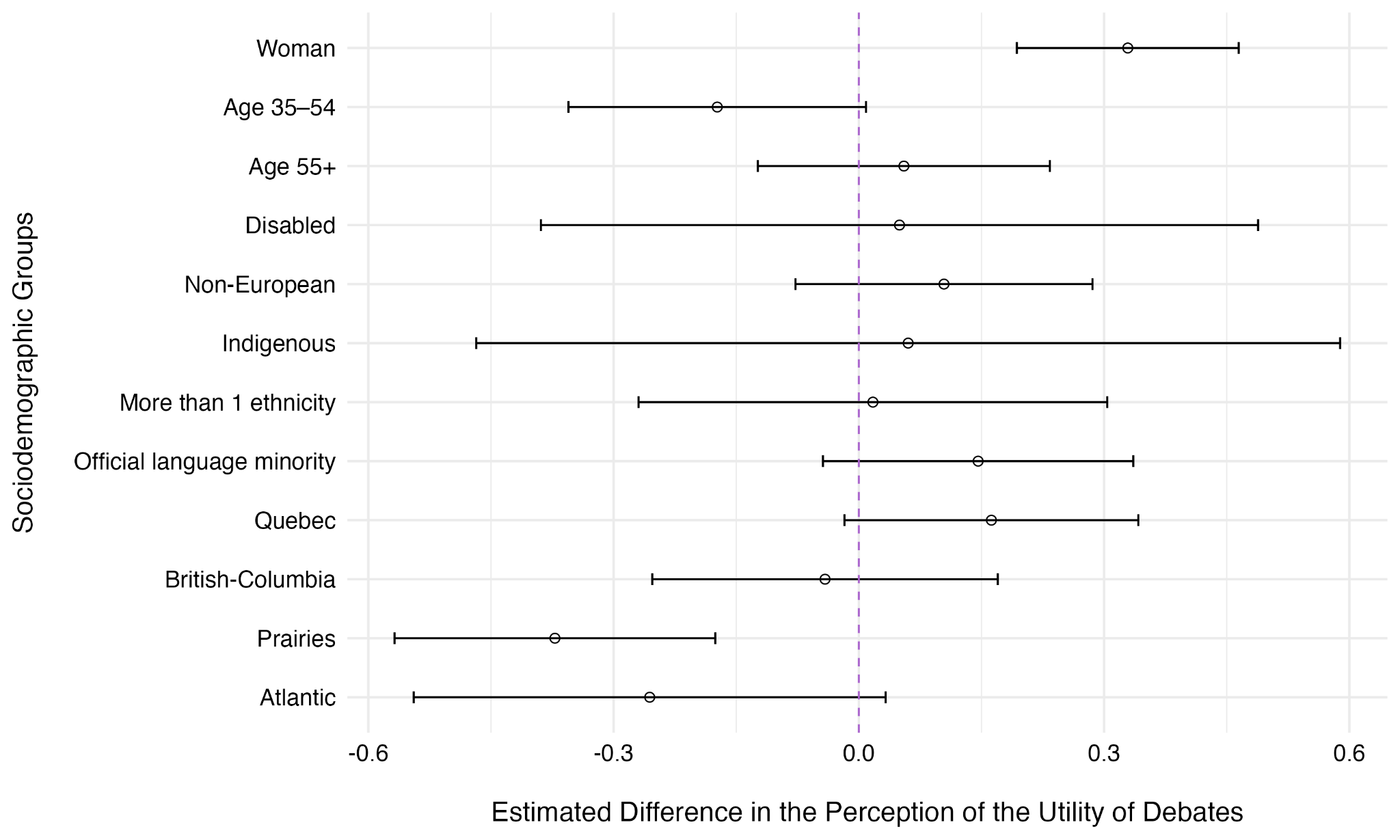

We can look at the sociodemographic correlates of perceiving the debates as useful using a regression analysis to understand significant predictors (Figure 12). Using the same demographic categories as before, we find that women are more likely to see the debates as useful than others and that those who live in the Prairie provinces are significantly less likely. Age, disability and language are not significant predictors.

Note: Points represent estimates from a weighted linear regression model with 95% confidence intervals. The dependent variable is a 0-10 scale based on the question “How useful do you think leaders’ debates are for Canadian democracy?”, where 0 means “not at all useful” and 10 means “extremely useful”. The reference category for age is 18-24. Disability is measured by participant self-identification; the reference category is no disability. The categories of ethnicity/ancestry presented are Indigenous, More than 1 ethnicity and Non-European, with European as the reference category. For official language minority, we consider both participants who learned French as their first language, still understand it, and live outside Quebec; or who learned English as their first language, still understand it, and live in Quebec. Not being an official language minority is the reference category. For gender, being a woman is coded as 1 and a man as 0 (the reference category). The variables for the different regions of Canada use Ontario as the reference category.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey, LDC Module (Weighted)

Viewership of the Debates

Overall Viewership and Across Demographic Groups

We asked people in the CES about their viewership after the debates had taken place. Overall, our data suggest that 43.7% of the population watched at least one debate, and 14.9% saw both debates. Viewership reached 35.8% for the English-language debate and 22.5% for the French-language debate.

When it comes to determinants of viewing, we again ran a regression with various demographic variables (see Figure 13). Consistent with previous research on political interest and engagement, our analysis suggests that men and those over 55 were more likely to watch a debate than women or those under 54. We see no differences based on disability status or across ethnic groups.

Note: Points represent estimates from a weighted linear regression model with 95% confidence intervals. The dependent variable is binary (1 if the participant responded they watched at least one of the leaders’ debates; 0 otherwise). The reference category for age is 18-24. Disability is measured by participant self-identification; the reference category is no disability. The categories of ethnicity/ancestry presented are Indigenous, More than 1 ethnicity and Non-European, with European as the reference category. For official language minority, we consider both participants who learned French as their first language, still understand it, and live outside Quebec; or who learned English as their first language, still understand it, and live in Quebec. Not being an official language minority is the reference category. For gender, being a woman is coded as 1 and a man as 0 (the reference category). The variables for the different regions of Canada use Ontario as the reference category.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey, LDC Module (Weighted)

Duration of Viewership

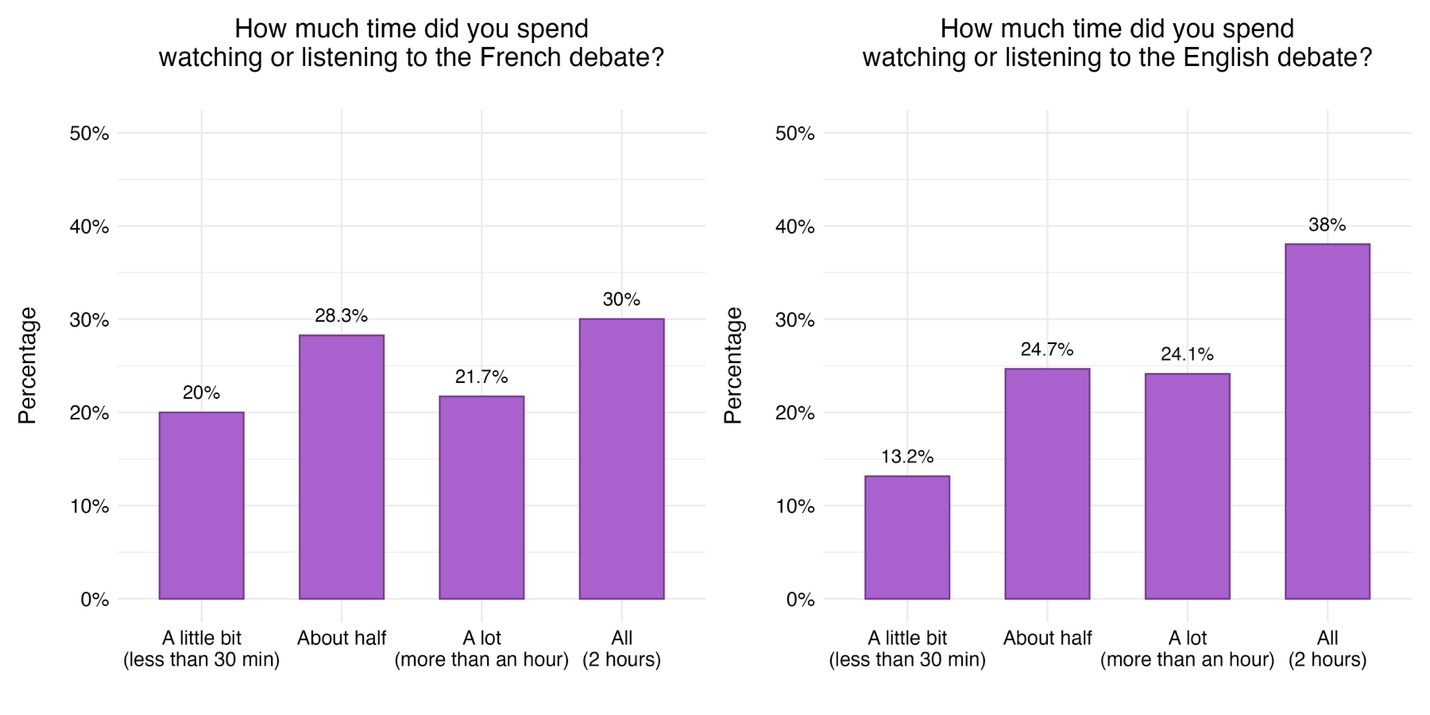

Our results in Figure 14 suggest that more viewers of the English-language debate reported tuning in for the whole time (38%), compared to the French-language debate (only 30%). A full 20% of those who indicated watching at least some of the French-language debate stayed tuned for less than 30 minutes. These results are skewed, however, by viewers who are less fluent in the language. If only those whose first language is French are considered, the percentage of people who watched less than 30 minutes decreases to 16%. The percentage of people who watched the entire debate rose to 35%, a percentage similar to that of the English-language debate.

Note: Analysis limited to those who reported watching the debate.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey, LDC Module (Unweighted)

Reasons for Not Watching the Debates

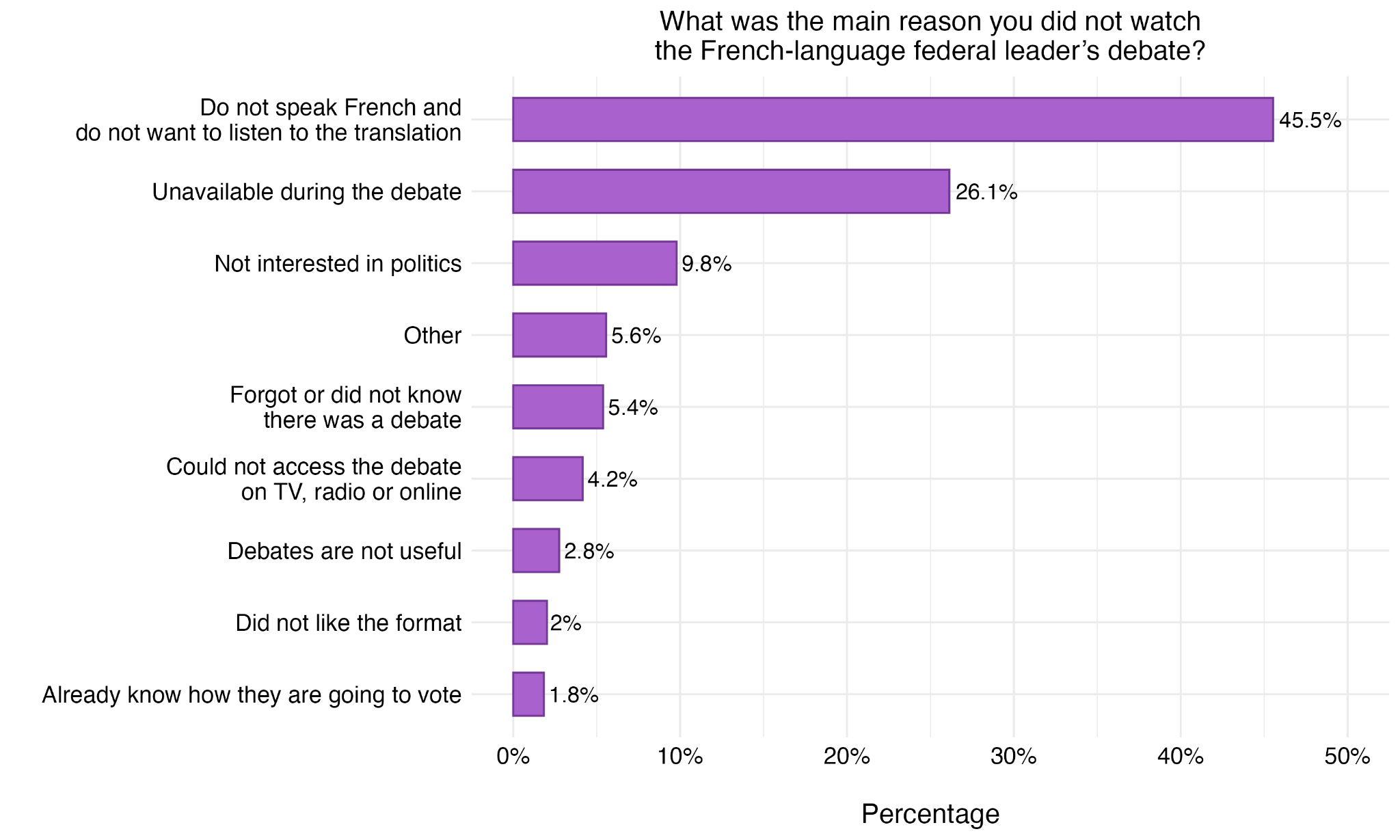

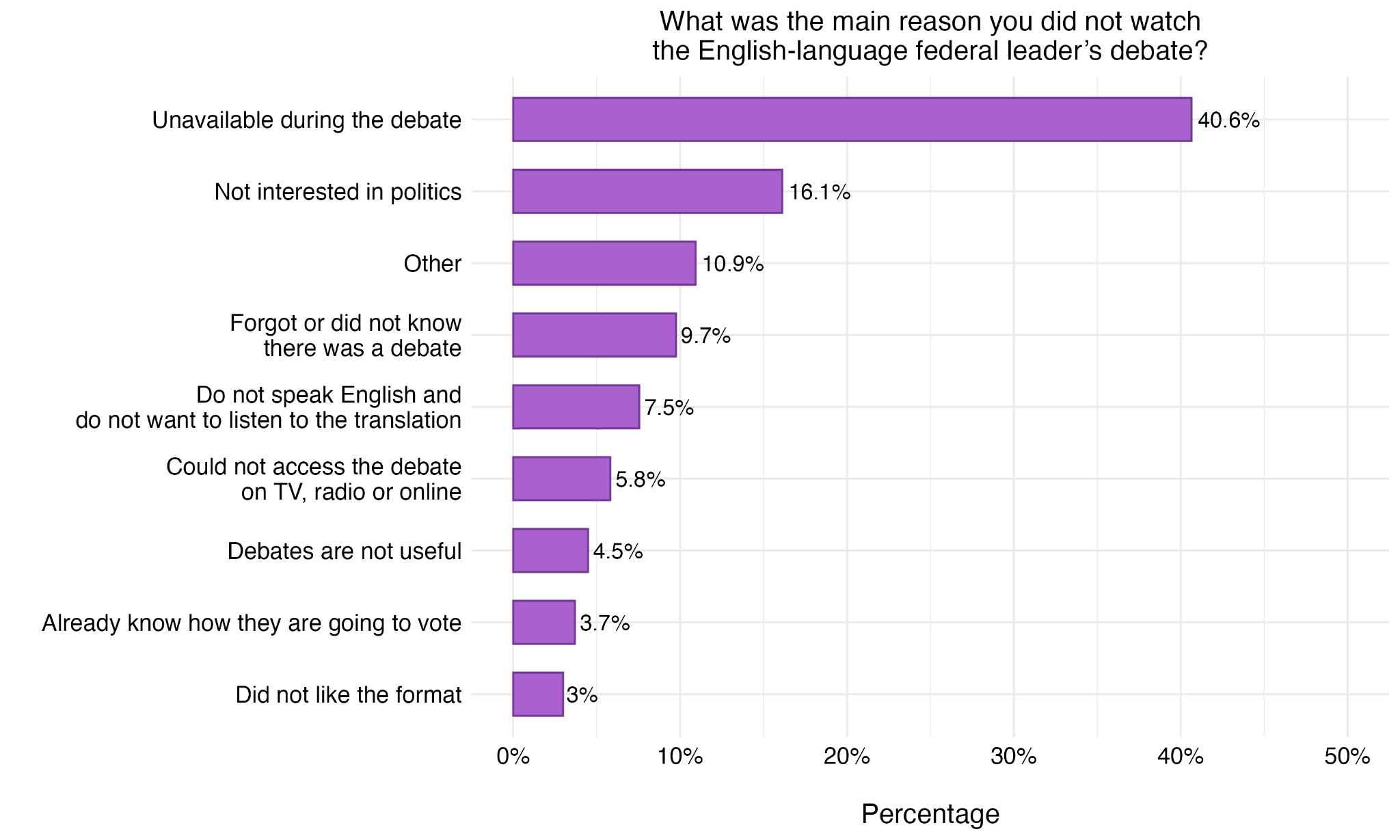

When it comes to not watching the debates, we gathered open-ended responses from the whole sample among non-viewers (of the French and English debates, separately). These are shown in Figures 15 and 16. There will be some overlap between these groups but also unique elements – people who watched one but not both debates. This is made clear because the most often-cited reason for not watching the French debates was language – people who did not speak French and did not want to listen to the translation made up almost 46% of the respondents. Direct comparisons are possible with the 2021 debate data, where we see that this finding is in keeping with the 2021 results. The relevant proportion who indicated language for the English debate was only 7.5%.

Setting aside language, being unavailable (too busy) was the next most common response, for both debates. After that comes being uninterested in politics. It is notable that the proportion of non-viewers that chose to abstain due to debate-specific factors (not finding them useful or not liking the format) was very small. This is a change from the 2021 results. It is also interesting that the number of people who indicated they did not watch because they had already made up their mind about who to vote for was very small (less than 4% in both debates). In 2021, that response was most common after being too busy, and represented about 15% of people who did not watch the French debate and about 25% of people who did not watch the English one. This suggests that the utility of debates might vary according to the competitiveness of the election.

Note: Analysis limited to those who reported not watching the French-language debate. The percentages are based on the qualitative categorization hand-coded for answers to the question (n=1,634).

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey, LDC Module (Unweighted)

Note: Analysis limited to those who reported not watching the English-language debate. The percentages are based on the qualitative categorization hand-coded for answers to the question (n=1,272).

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey, LDC Module (Unweighted)

Evaluation of 2025 Debates

To get an understanding of how Canadians felt about the debates, we included questions in the focus groups and the CES module. We begin with an analysis of focus group respondents, as they were collected during and immediately after the debates. This provides a useful “gut reaction” to the debates which are less likely to be influenced by post-debate conversations and media coverage.

Focus Group Evaluations

When participants were asked about their initial impressions of the debate, they generally expressed appreciation for the structure and the interactive aspect of the exchanges between the leaders. Additionally, the topics discussed appear to have aligned with their expectations. While participants who listened to the debate in French generally enjoyed it and found the topics pertinent, they also remarked that the exchanges remained at a surface level.

“I thought the debate had a wide range of issues that… This election really needs to be about. [...] I like the format where they got to answer questions [that were asked] by others [so they could] give a response.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

“The thing that I liked very much about it all was the structure, the breaking it into the five categories and allowing for the very short, focused discussion around each of those five and not letting it sort of linger back into it [...] that was well done.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Ben, j'ai été surpris, ça a passé rapidement avec les différents thèmes qui étaient précis, tout ça. Comme l’ont dit les autres participants, on n'a pas appris grand-chose, mis à part un petit peu d'humour en apprenant que trois candidats sur quatre font leur épicerie eux-mêmes [...]. Sinon, ben, on tournait toujours de sujets qui sont réguliers dans ce genre de débat, voilà.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

Several participants mentioned that they disliked it when leaders spoke over one another, but respondents suggested that it was better than previous debates they had seen. They seemed generally satisfied with the moderators’ efforts to maintain order in both debates. This will be discussed further in the section specifically addressing the moderation.

“At first it was a little chaotic just because there was so much talking over each other, which I really didn't like. But as for any debate, I mean the Canadians are pretty civil. ” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Je m’attendais à plus de cacophonie, il n’y en a pas eu.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #2

There was disappointment regarding the informative aspect of the debate and the substance of the leader's answers, especially the lack of more concrete proposals. Some respondents believed that leaders were merely there to share prepared campaign messages.

“There’s a lot of things said with nothing said. [...] They'll bring up something that's interesting to them, but won't say practically how they're going to make it happen” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

“Je me suis fait garrocher des promesses électorales sans quoi que ce soit qui vient de plus concret, comment y arriver.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

“C’est toujours un peu l’impression de faire le tour de concessionnaire de voitures usagées. On s’attarde beaucoup sur la peinture, puis on ne sait pas vraiment ce qu’il y a en dessous du capot.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #2

Many participants appreciated the dynamic and flexible format of the debate. The fact that the leaders had the opportunity to question or answer each other directly was seen as a way of stimulating exchanges and bringing out their personalities. The variety of the segments was also mentioned as something positive. At times, the exchanges seemed more cacophonous, but this was generally temporary, and participants accepted that this was part of the reality of a debate. The importance of good guidance from the moderator was again stressed.

“I understand that it's meant to help them show their charisma and how well they handle pressure, but I do wish everybody got their turn to speak without interruptions.” – Participant in the English Chat #2

“I think it’s good and balanced – allowing everyone to answer some questions in turn but also let them debate directly which will bring out the personality and show the character beyond the usual scripted speeches.” – Participant in the English Chat #2

“Moi j'ai aimé la dynamique que ça, ça l'a donné. [...] On avait un point de vue assez rapide qui donnait un peu d'action, qui était intéressant pour l’auditeur.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

Only the English-language debate included a closing statement from each leader. Although these interventions were perceived as scripted or expected, participants largely thought they corresponded to a natural and respectful way of concluding the exercise, allowing the leaders to thank the audience and reiterate their main message one last time.

“I like the closing statements and I know it is probably very scripted [...] But I like that at the end they have the opportunity to kind of put an [appeal] there one last time. Say thank you to the audience for being here and appeal for and ask for a vote. I think it’s just a polite way to end the whole evening.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

Respondents to the French-language debate also stressed that the leaders' final statements left an important final impression and were therefore surprised by their absence.

“Moi, je m’attendais quand même à avoir une déclaration de fermeture. L’ouverture il y a tellement de choses qui se disent dans le débat qu’à un moment donné, ça ne sert pas à grand-chose. Mais une fermeture, c’est comme la dernière impression que les gens ont de toi, puis c’est ce dont ils vont généralement se souvenir un peu plus.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

Regarding the flow of the debate, several participants felt that the exchanges were too fast and sometimes superficial due to the large number of topics covered in two hours. It was suggested by some participants that breaks between segments would have facilitated understanding and kept the audience's attention. The length of the debate was generally perceived as adequate, if not a little too long. Some people mentioned their family responsibilities. Several also mentioned that the debate became repetitive towards the end, which can contribute to a loss of attention.

“Some of it was just a little too fast because you are trying to process what they're saying […] and then by the time you're still thinking about that topic, it's like, ‘OK, now we're going to Gaza. Now we're going to this.’” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“At an hour and a half, my attention started to wander into what do I have to do tonight before I go to bed?” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Deux heures c’est long quand on a une vie de famille. Puis tu sais, je me demande, je n’ai pas noté à partir de quelle minute j’ai fait ‘OK ouais, je pense que j’ai compris un peu les grandes lignes, puis qui a l’air d’avoir plus maîtrisé son contenu’. Puis est-ce que toutes les questions auraient été vraiment nécessaires? Parce qu’on était beaucoup en surface.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #2

CES CPS Survey Evaluations

While focus groups allowed for immediate and more nuanced reactions to the debates as they were occurring and right afterwards, the CES survey provides a more general picture of the reaction of Canadians in the days and weeks following the debates. These questions allow us a sense of how public opinion about the debate emerged in their wake.

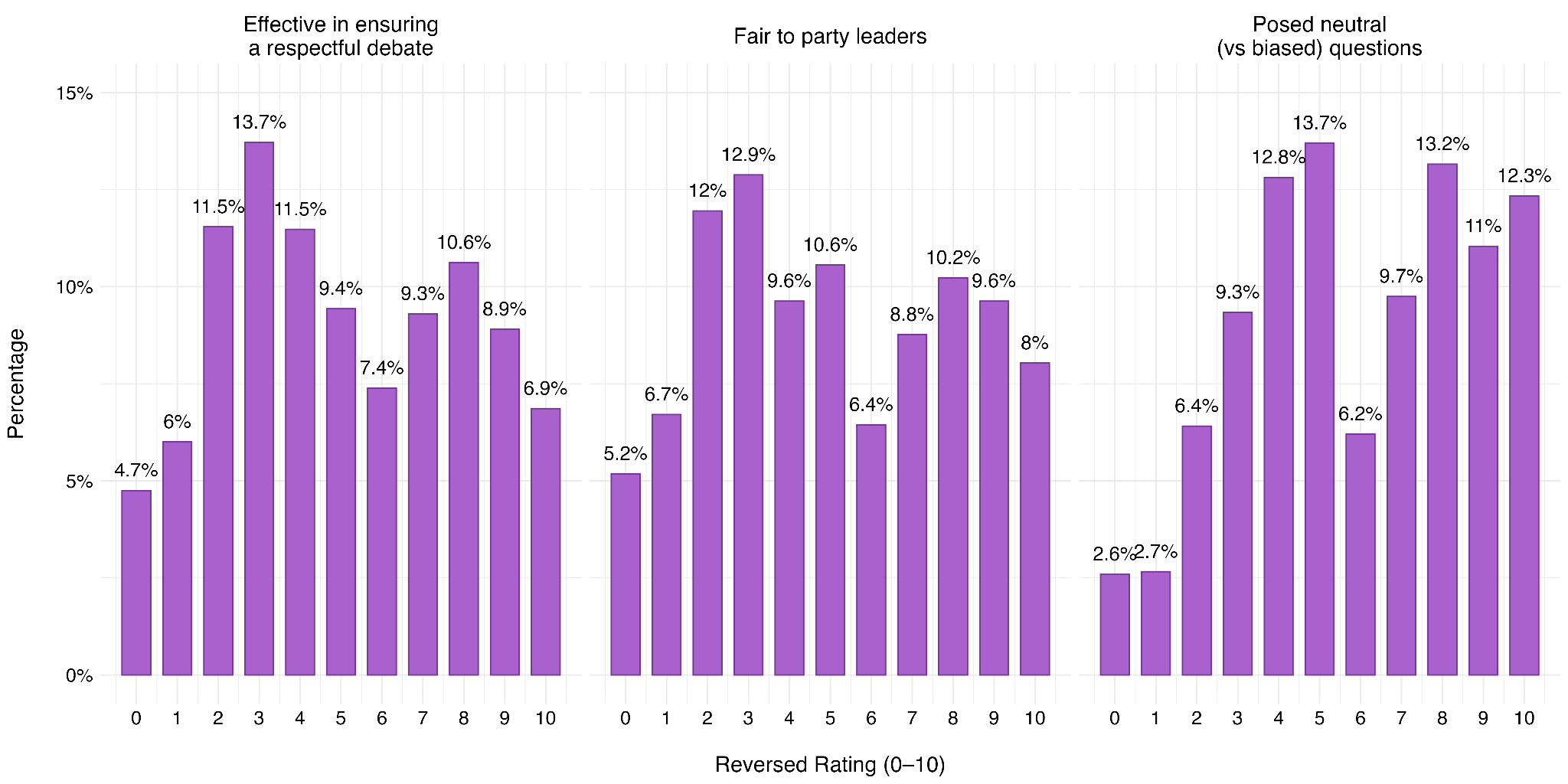

The CES included specific questions about the moderators – whether they were fair to leaders, effective in ensuring a respectful debate, and neutral or biased. Amongst those who watched the debates (English and/or French), Figure 17 shows the distribution of responses on a 0 to 10 scale (reversed from how it was gathered so that 10 is more effective, more fair, and more neutral). From Figure 17 it is clear that people’s evaluations of the moderators varied considerably. A comparison of means for the English and French debates, individually, hides this important variation, but it does allow for a more direct comparison. The English moderator was rated slightly (but significantly) lower in terms of their fairness and effectiveness compared to the French-language debate, but both moderators received the same mean rating when it comes to posing neutral questions.

Note: Survey responses for debate viewers only. The scales have been reversed to facilitate interpretation.“Effective in ensuring a respectful debate” now ranges from 0 = “Not effective at all” to 10 = “Very effective”; “Fair to party leaders” ranges from 0 = “Not very fair at all” to 10 = “Very fair”; “Posed neutral (vs biased) questions” ranges from 0 = “Very politically biased” to 10 = “Very neutral”.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Unweighted)

We asked people who did not watch the debates whether they had heard anything about the debates. Since the content of debates and the impressions left on viewers can have indirect effects on people through conversations, it is important to understand whether viewers and non-viewers had different impressions. It is notable that an overwhelming proportion of non-viewers report that they had not heard anything about how the moderator ran the debates from friends, family or the media (86% for the French debate, 91% for the English debate).

Even though not that many non-viewers reported hearing about the debates, we can compare impressions of the debates among viewers and non-viewers. The results indicate that viewers of the debates consistently rated the moderators more positively than non-viewers. Despite this trend, there is no significant difference between the evaluations of viewers and non-viewers. On the other hand, while among viewers of the debates the ratings for the French moderator were significantly more positive than those for the English moderator, there is no significant difference between the two moderators among people who did not watch. Comparing viewers and non-viewers, though, on the dimension “Fair to party leaders”, English debate viewers gave an average rating of 5.0, compared to 4.8 among non-viewers (where 0 means not very fair at all and 10 means very fair). Similarly, for the French debate, viewers rated fairness at 5.4, whereas non-viewers gave an average of 4.9. In terms of "Effective in ensuring a respectful debate", English debate viewers gave an average rating of 5.0 compared to 4.5 for non-viewers (on a 0-10 scale where 10 means very effective). For the French debate, viewers assigned a mean rating of 5.3 compared to 4.9 from non-viewers. Clearly, more positive impressions came from actually watching the debates.

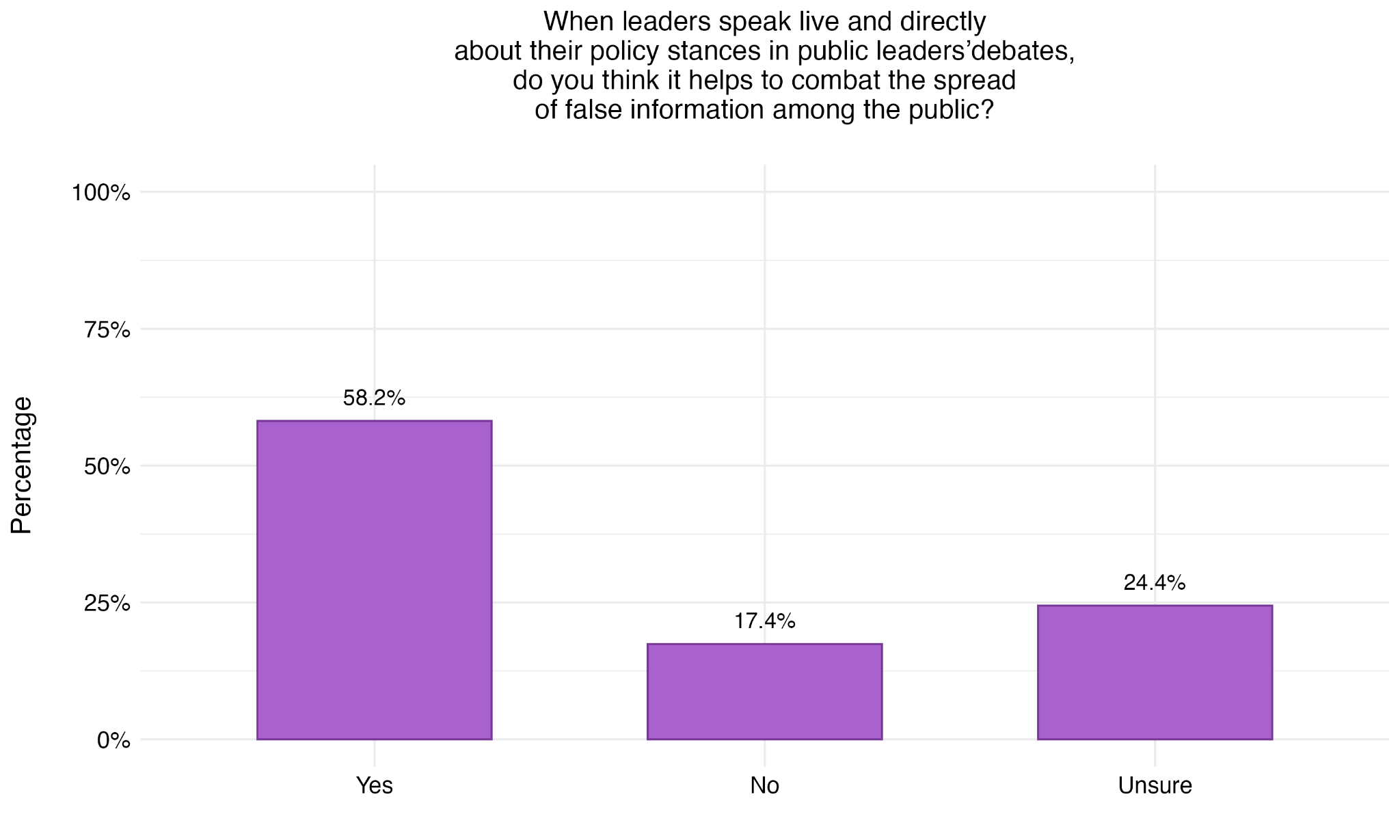

Debates are also one of the only times that party leaders can speak directly to such a large audience of voters. We asked whether respondents thought hearing from leaders directly helps to combat the spread of false information among the public. A clear majority responded favourably (Figure 18).

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Impact of Watching the Debates

By comparing those who did and did not watch the debates in our sample, we can get a sense of whether there are relationships between viewership and political engagement. We cannot claim a clear causal link, given that viewership and engagement could be both related to some other, unmeasured value, but we can better understand what behaviours are associated with watching debates and get a sense of whether watching spurs activities by comparing responses to those acquired prior to the debates airing.

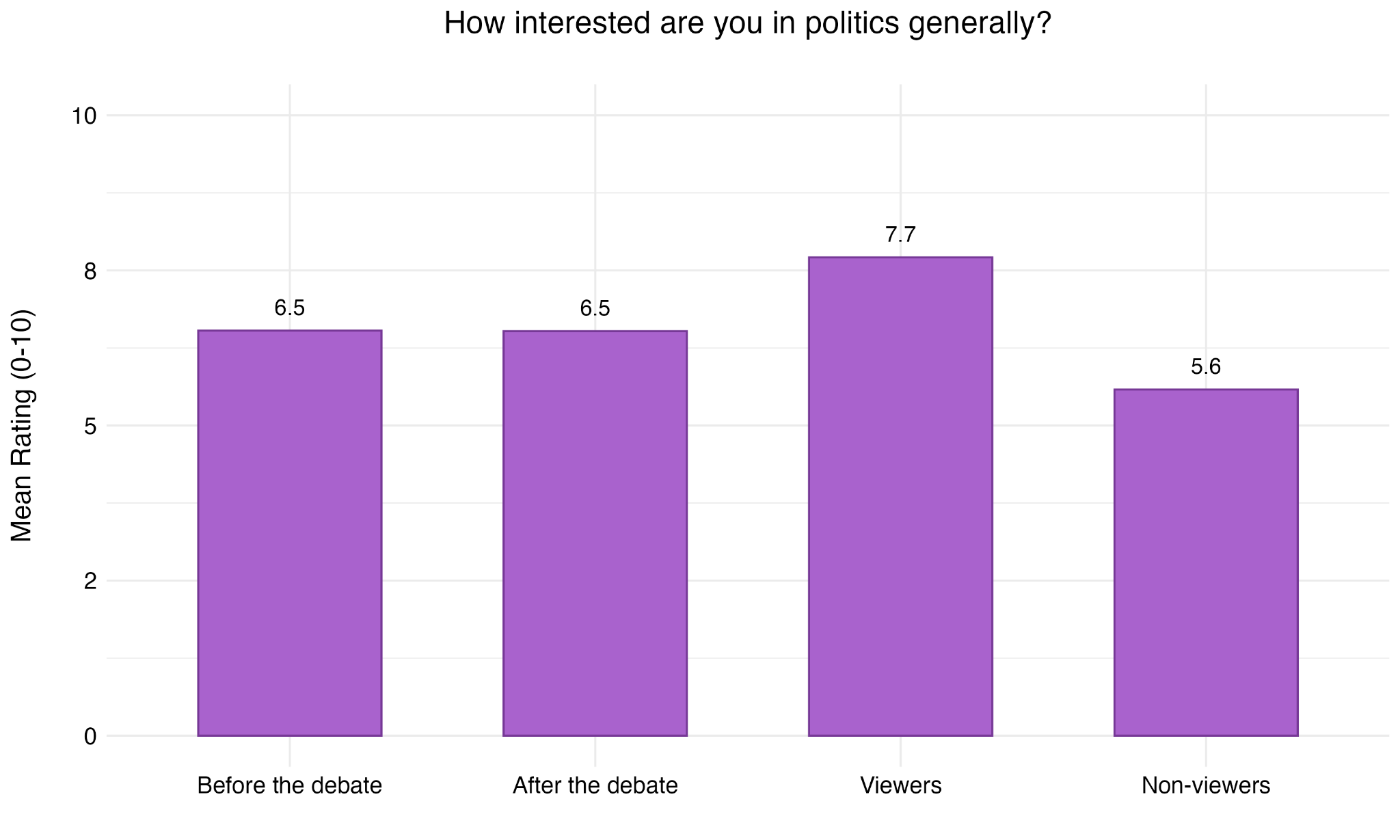

We first looked at political interest (Figure 19). Prior to the debates, average interest was 6.5 on a 0-10 scale. We see a clear difference between debate viewers and non-viewers after the debate, however. Viewers are much more likely to report political interest compared to non-viewers. This is likely because those more interested in politics are more likely to watch debates (given that non-debate watchers are less interested), rather than that the debate increased political interest. This is supported by the after debate average (second column), which is almost the same as it was prior to the debates.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

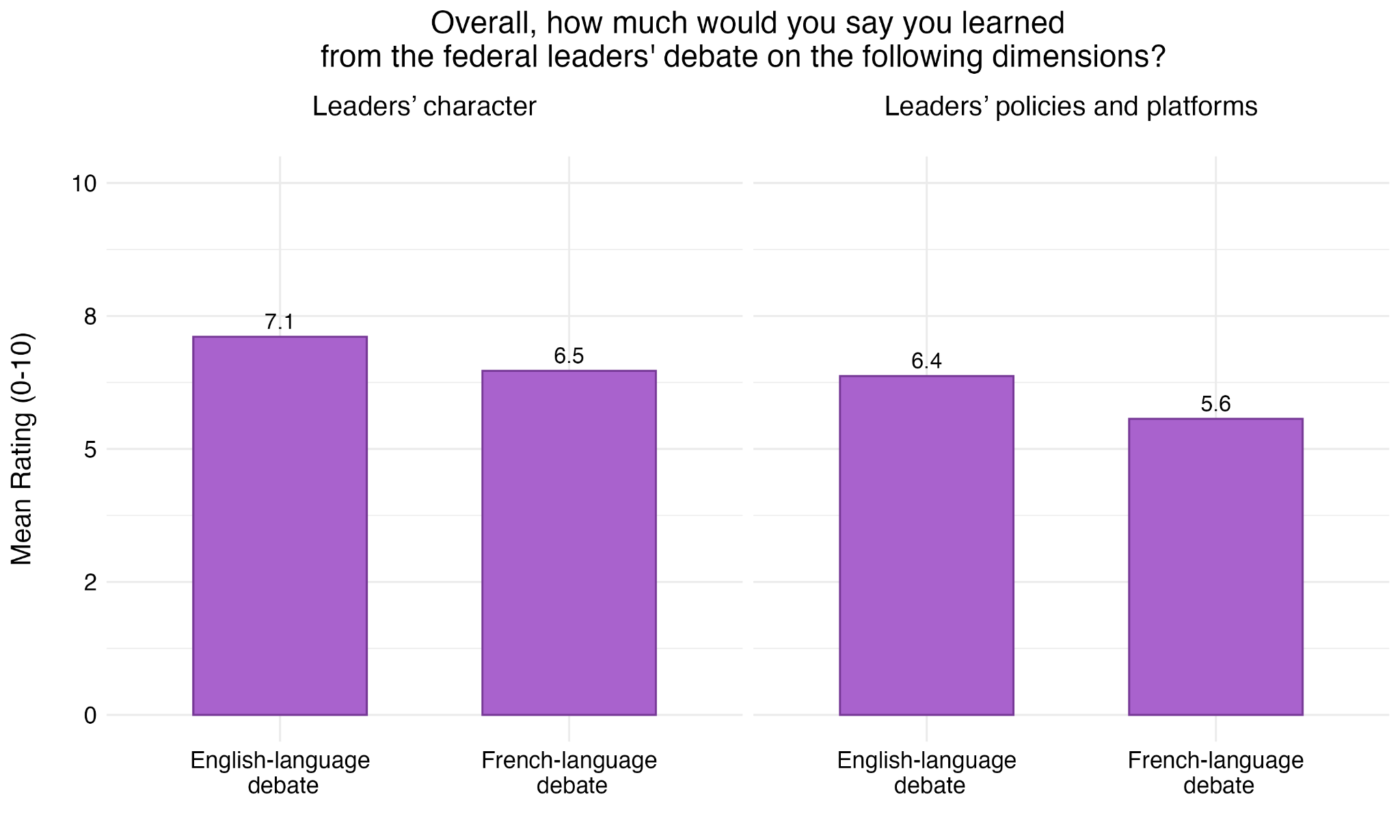

Respondents were also asked, on a scale of 0-10, how much they learned about “Leaders’ character” and “Leaders’ policies and platforms”. The responses in Figure 20 suggest that people learned more about the character of the leaders, especially in the English language debates, and less overall about policies and platforms, especially in the French debate.

Note: Analysis restricted to debate viewers. A rating of 0 means the respondent self-assessed as learning nothing and 10 means they think they learned a lot.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Unweighted)

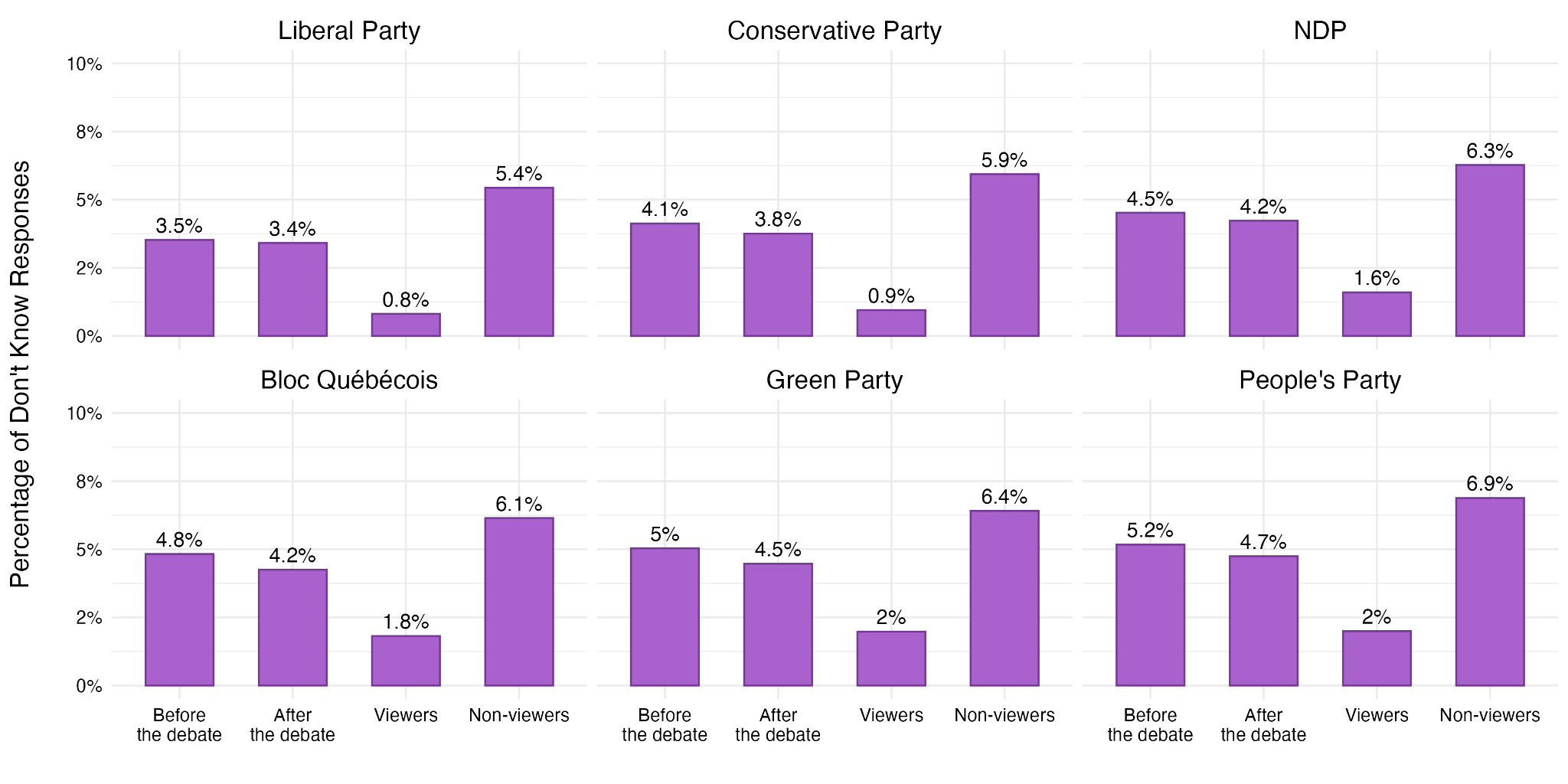

Another way to assess the impact of debates is in terms of viewers’ and non-viewers’ ability to rate the parties and leaders. Here, we are not interested in how they rated leaders, but simply whether they felt capable of making an assessment. We turn to the proportion of respondents who answered “don’t know” about parties (Figure 21) or individual party leaders (Figure 22). Clearly, the ability to provide an assessment (regardless of if it was positive or negative) was substantially higher for those who watched the debates.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Interestingly, the assessment gap is much larger for party leaders than parties themselves for smaller parties that participated in the debate (Singh, Blanchet). A key data point here is that this gap is also present for leaders that did not participate in the debates (May, Bernier). This suggests that debate viewers are more knowledgeable about current political choices compared to non-viewers, rather than the debates themselves improving Canadians’ abilities to assess political leaders.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

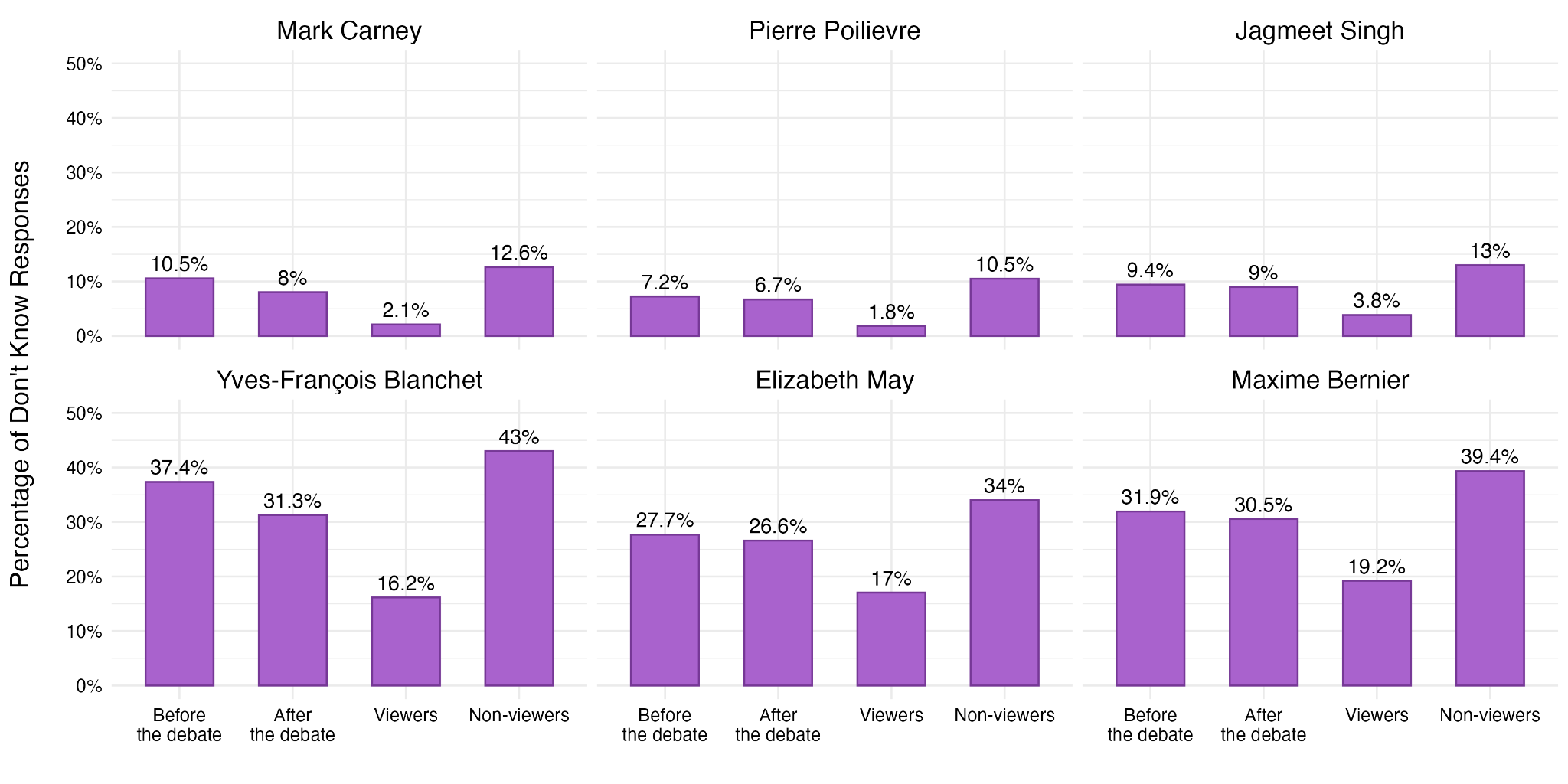

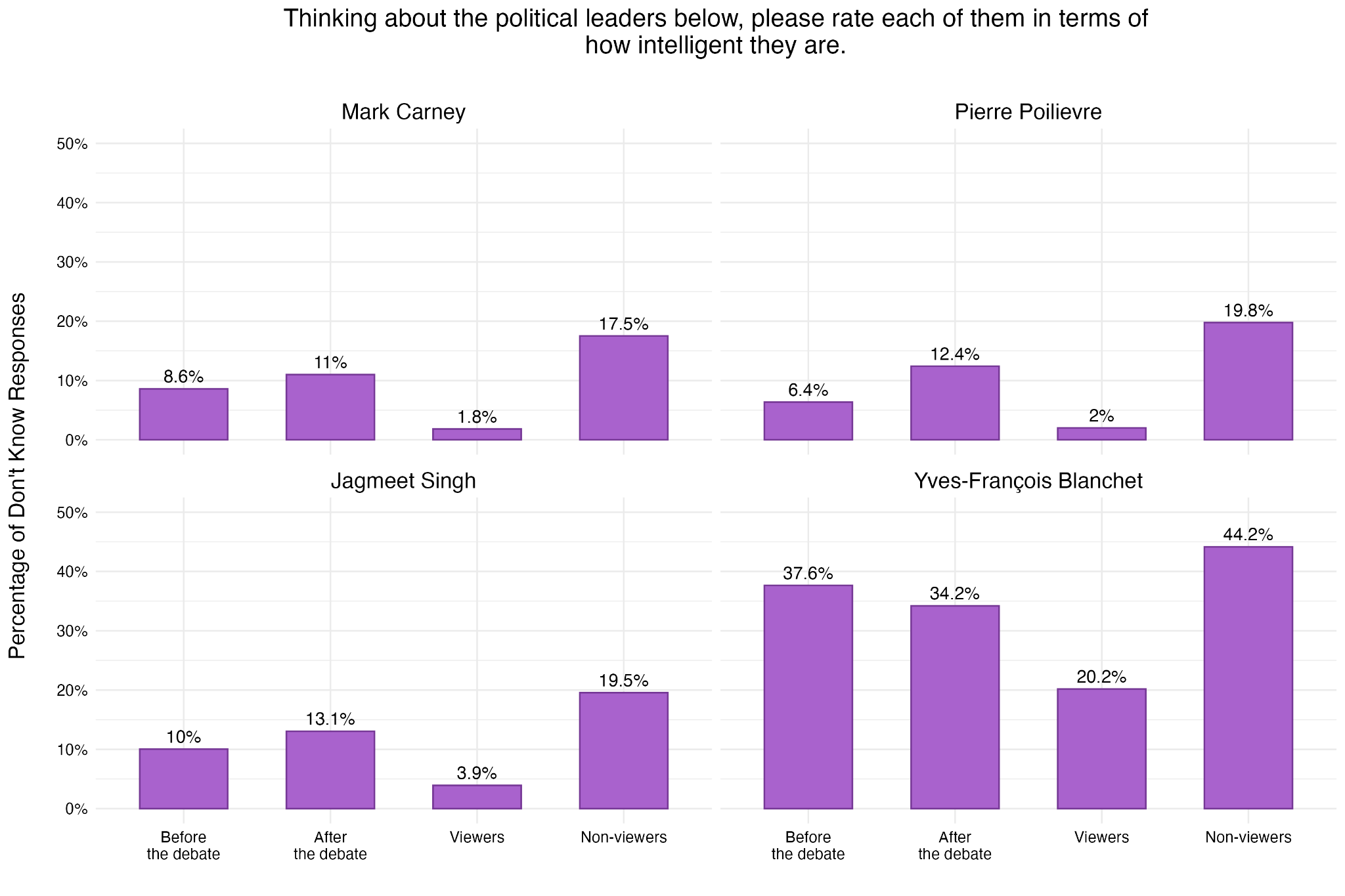

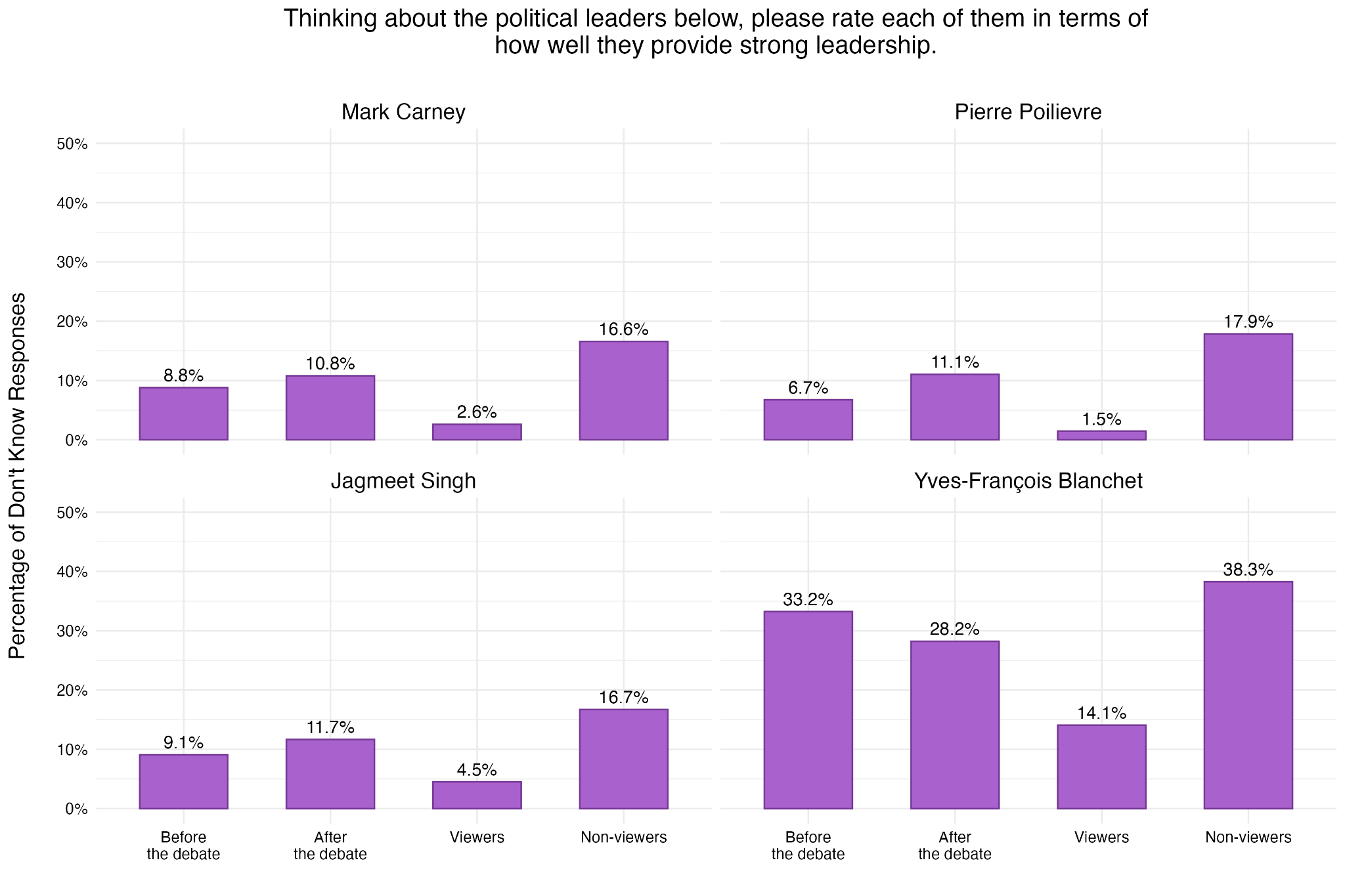

Another example of differences between viewers and non-viewers, which may have been impacted by seeing the debates, is the ability to evaluate party leader personalities. Figures 23-25 shows differences in “don’t know” responses for ratings of leader intelligence, ability to provide strong leadership, and how much they care about people. In these figures, we report the percentage that responded that they did not know how to rate each leader, or in other words, those who could not evaluate the leader on each dimension. In every case, non-viewers has a harder time evaluating the leader.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

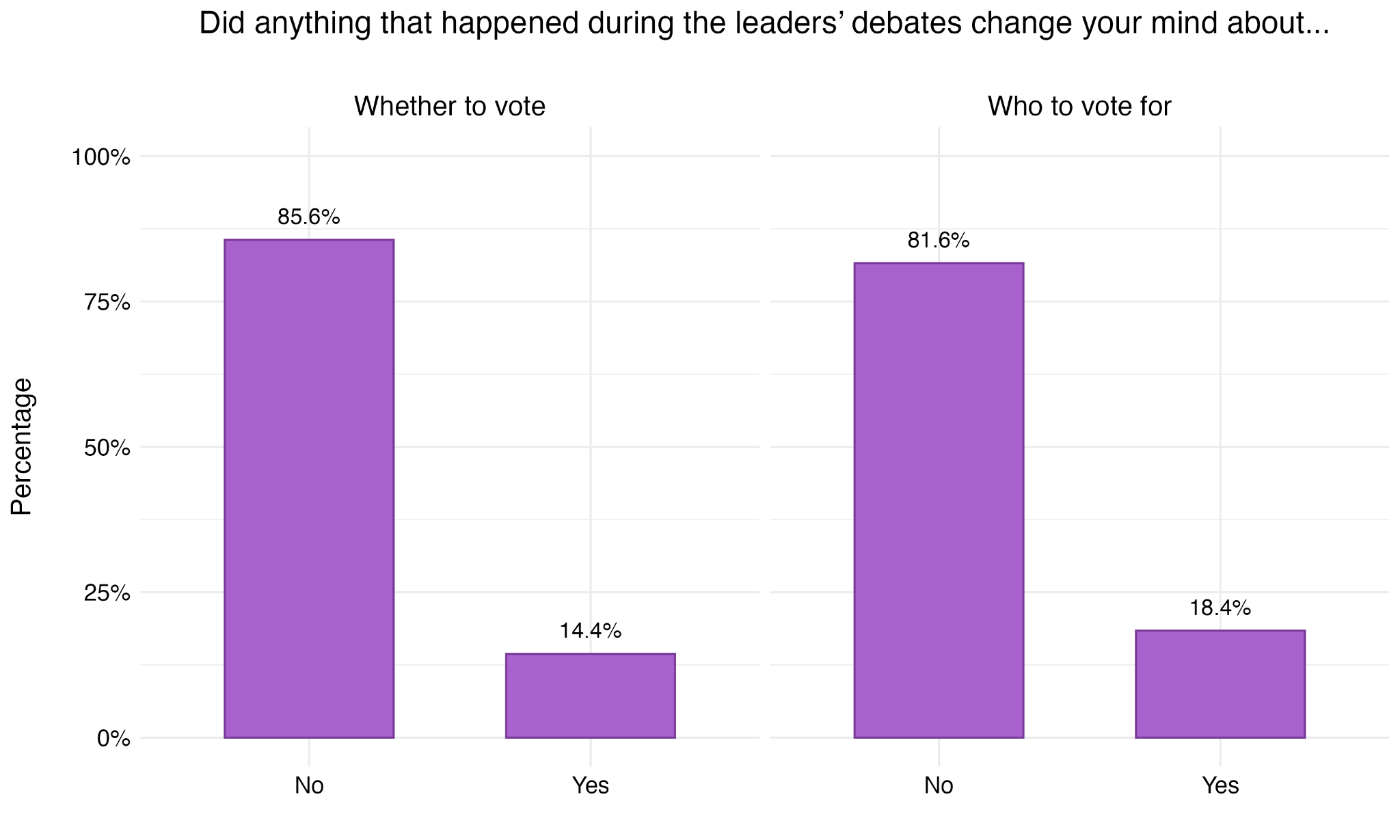

Along with the capacity to assess political actors, we also asked Canadians directly if anything during the debates changed their minds about whether to vote and who to vote for. The overwhelming response, over 80%, was “no.” In other words, most Canadians who watched the debate told us that the debate did not change their minds. This is, perhaps, not surprising given that many voters enter an election campaign with an idea of whether they are going to vote and who they are going to vote for. As we have seen, evidence suggests that debate viewers are probably more interested and knowledgeable going into debates. This does not suggest that the debates are meaningful, though. As we saw earlier, Canadians expect debates to occur. They tell us they learn things, especially about the leaders’ characters, and they think they are useful for Canadian democracy. And while those who say yes about changing their minds are a small percentage (14.4% and 18.4%), it is still an important minority who not only learned, but report deciding based on what occurred during the debates.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Unweighted)

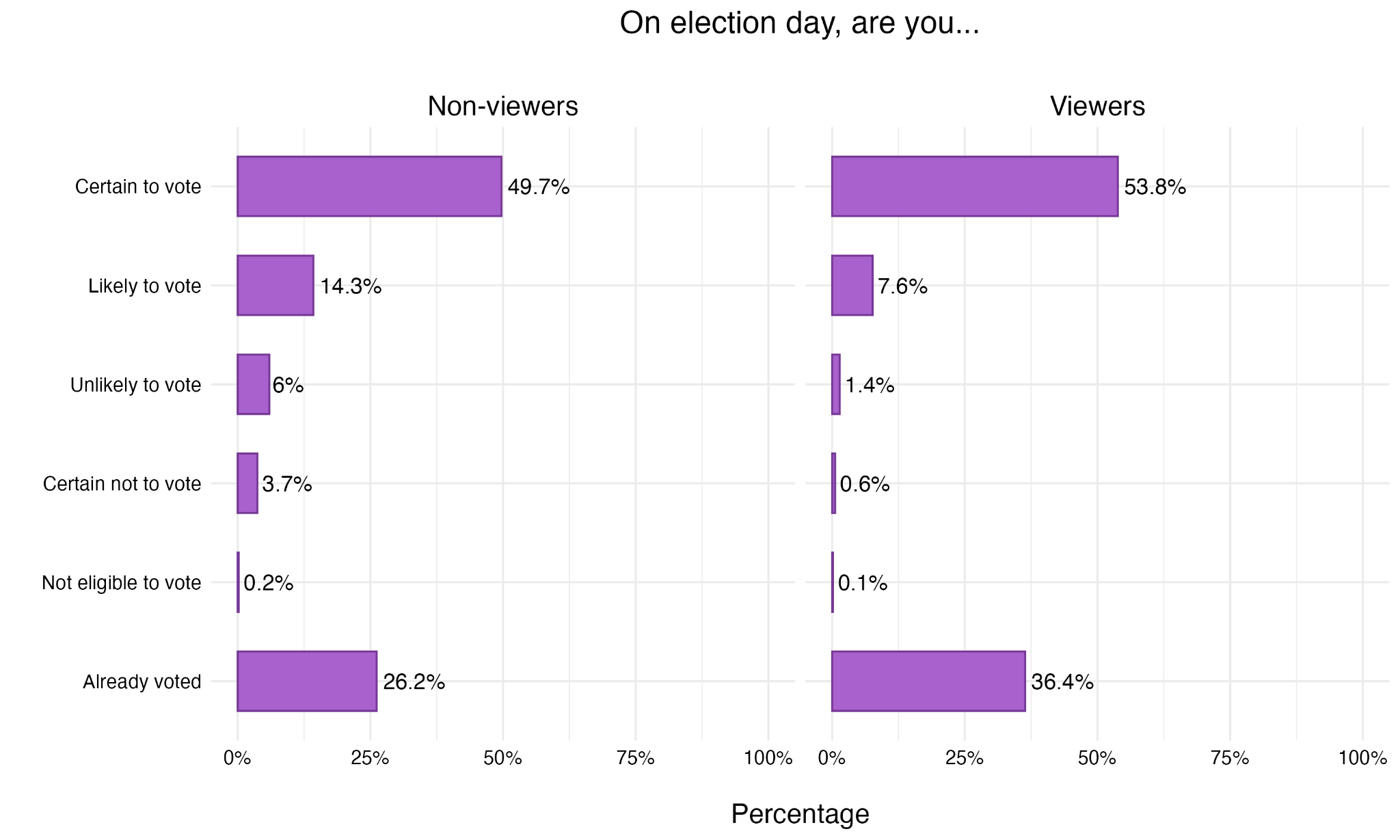

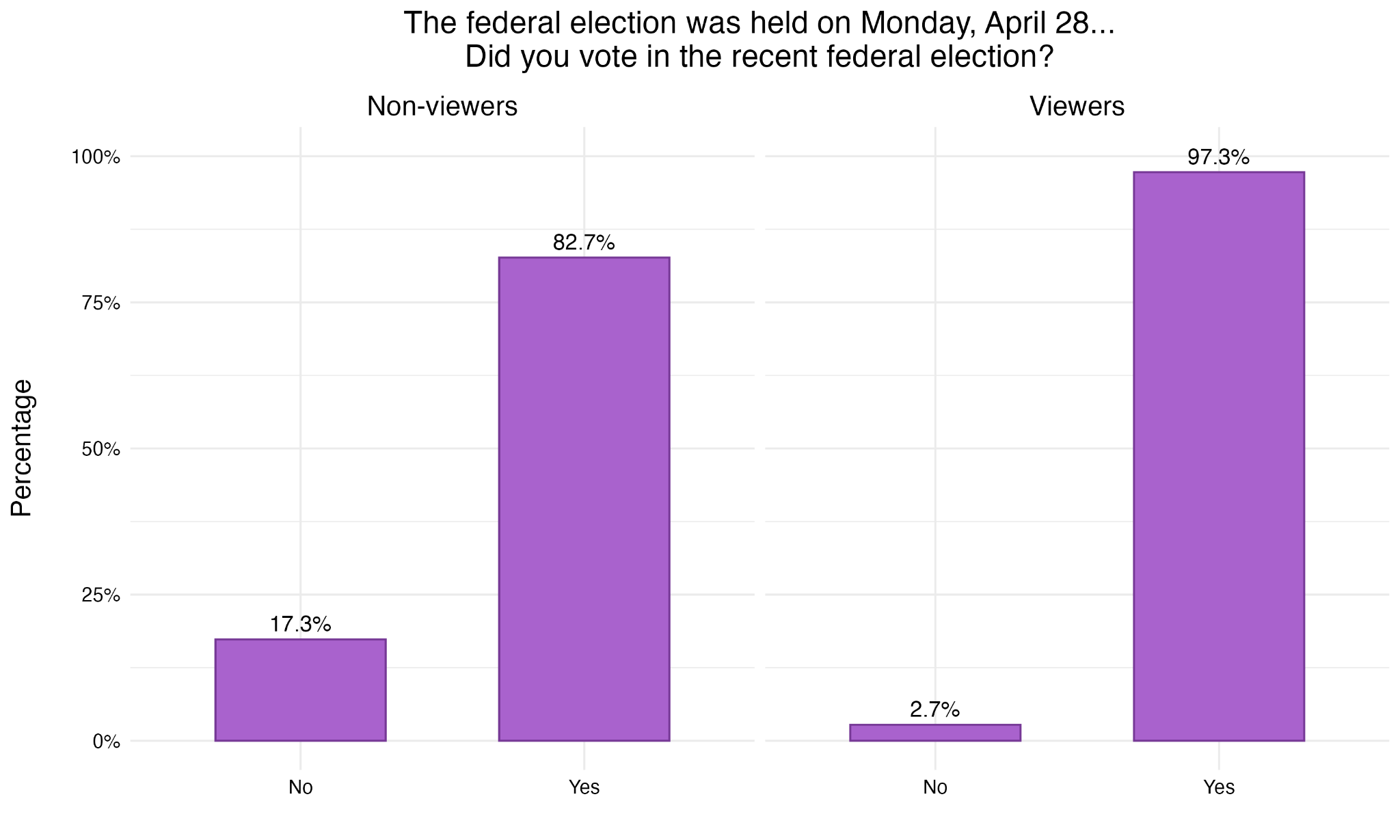

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the relationship between watching the debates and political engagement already reported, we also see that debate viewers expressed more intent to vote (during the campaign; Figure 27) and reported voting more (after the election; Figure 28).

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

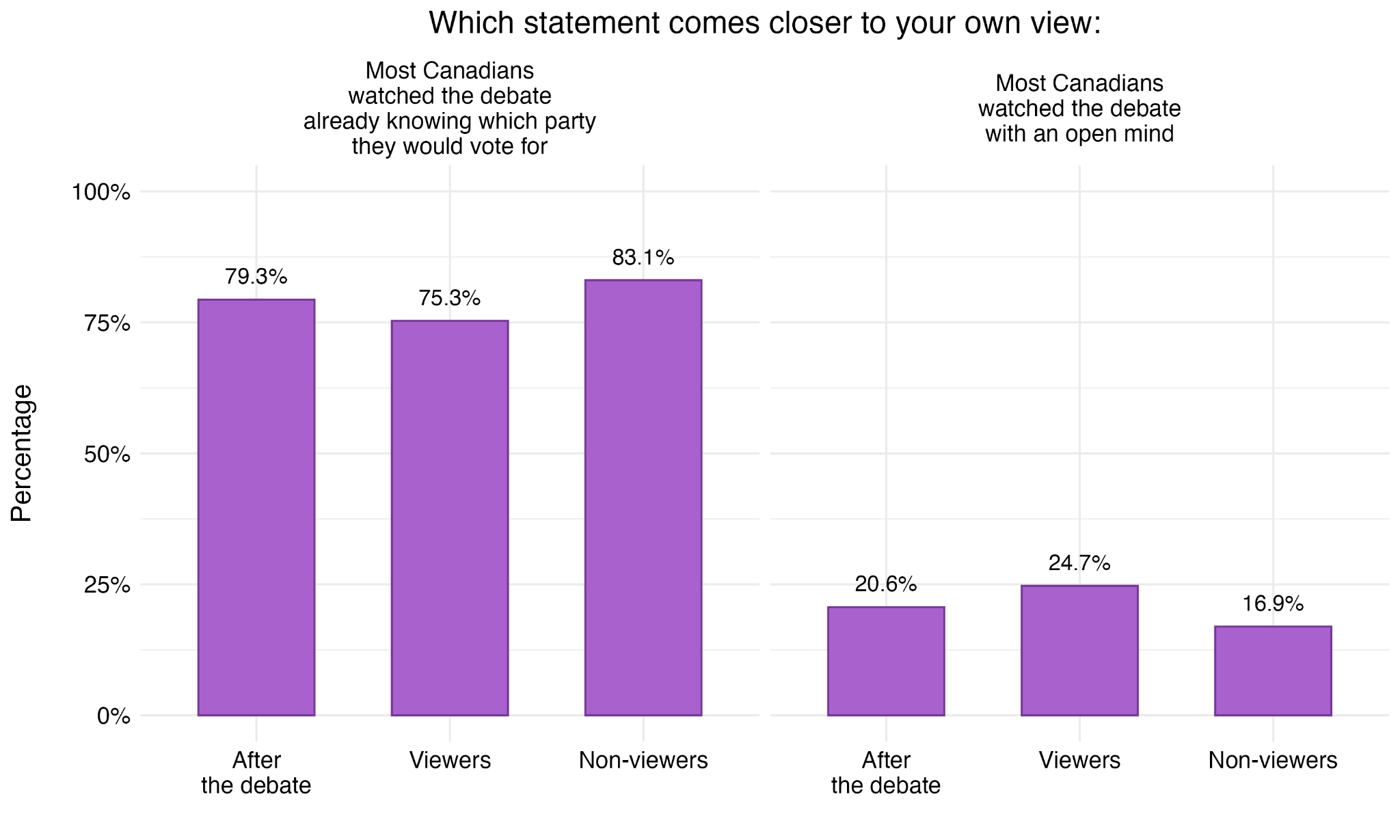

These findings are reinforced by responses to a question about whether Canadians who watch debates already know who they will vote for or watch with an open mind (Figure 29). At least three-quarters of respondents indicated they thought most people had already developed their vote choice before watching a debate. This opinion is strongest among non-viewers, suggesting a potential reason that they did not tune in.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

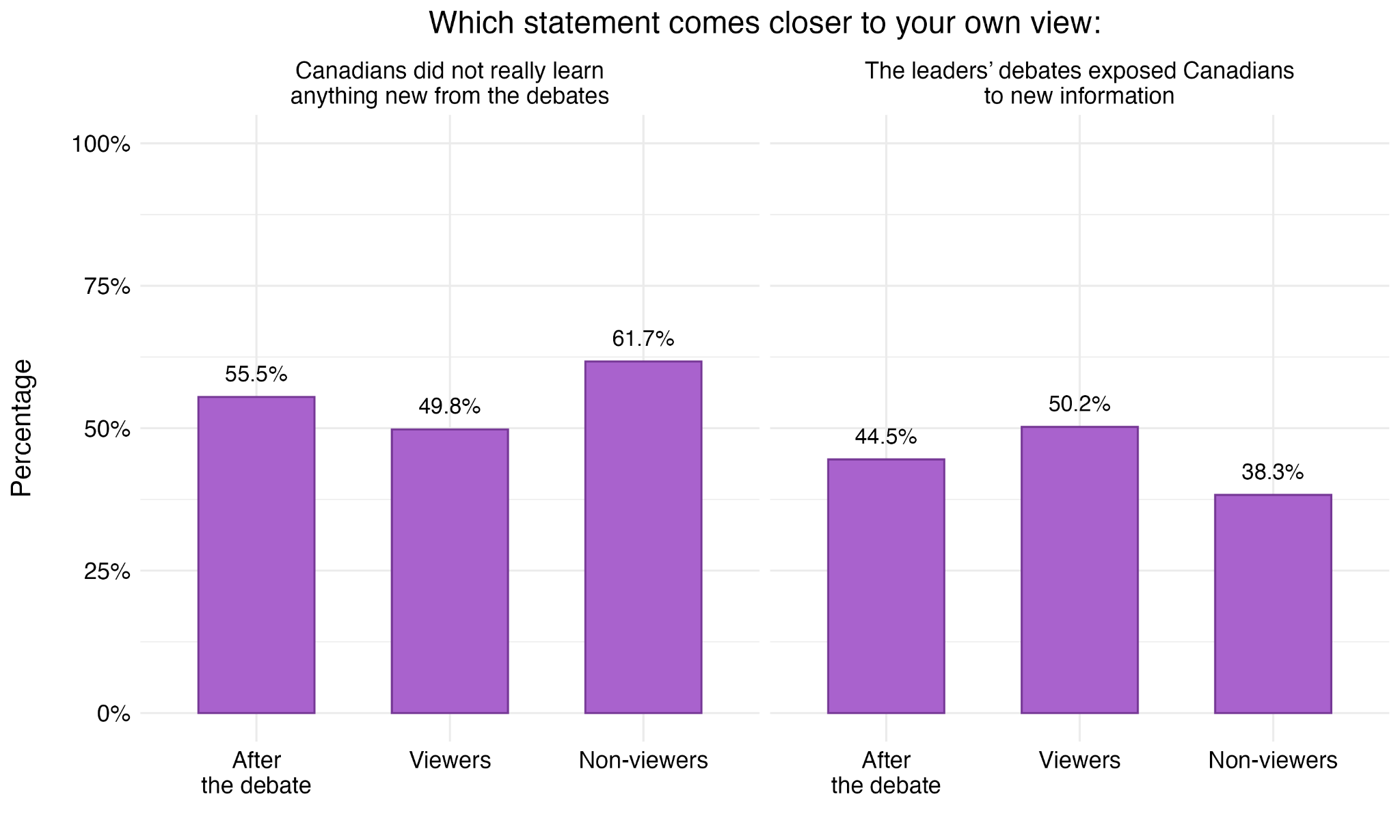

Also interesting are assessments of what was gained from watching the debates. Overall, a slight majority of CES respondents agreed that Canadians did not really learn anything new from the debates, compared to being exposed to new information (Figure 30). The balance is slightly reversed among those who did watch the debates, but the perceived lack of learning is more pronounced for those who did not watch. Again, this might be a biased stance related to the choice to not watch the debates, but it is still striking.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

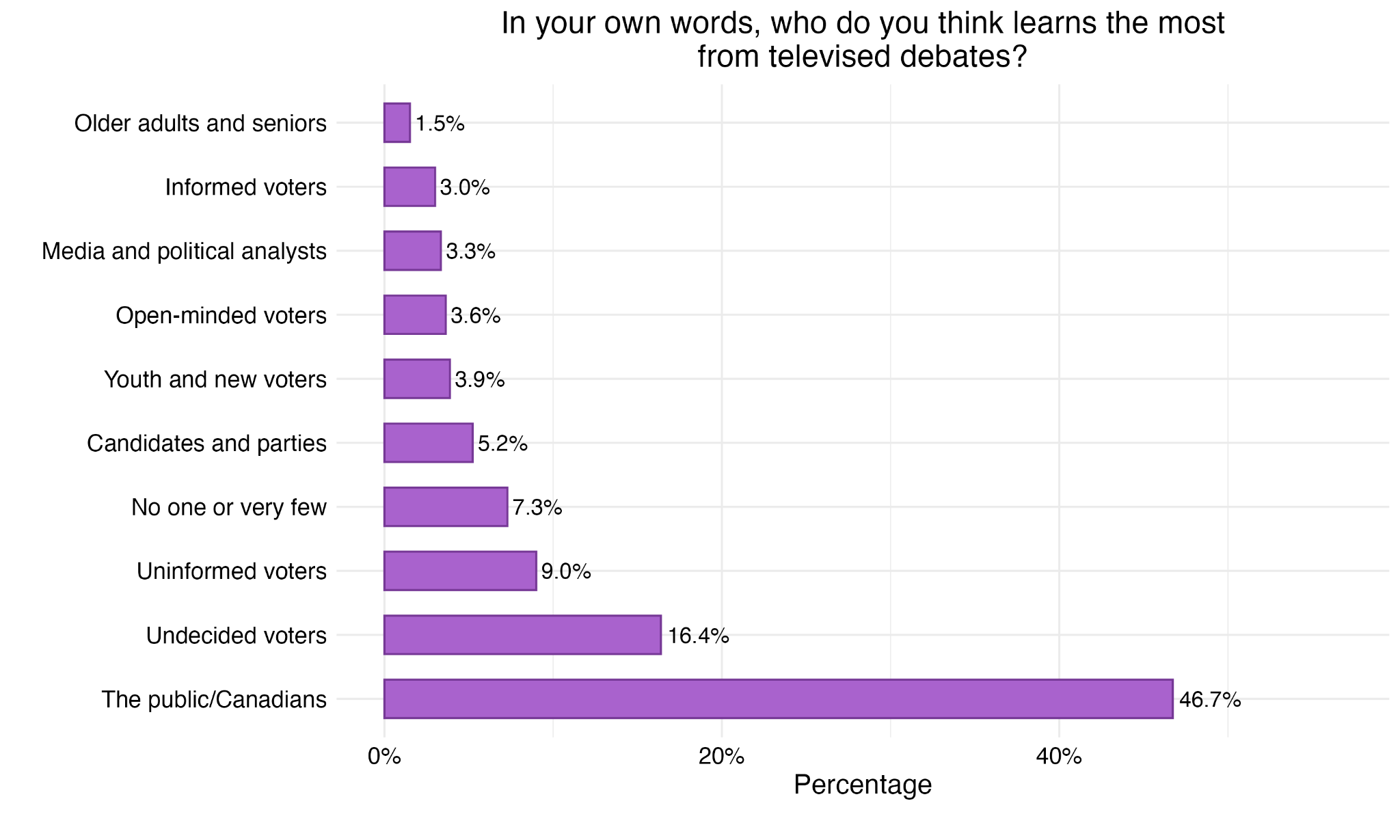

Despite these views, most respondents believed that the Canadian public benefits from debates (Figure 31). Most respondents did not identify a subgroup that was particularly likely to benefit, though undecided and uninformed voters were the second and third most likely groups mentioned.

Note: Percentages are based on the qualitative categorization of open-ended responses in both English and French (n=873).

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

Preferences about Debate Format and Future Debates

There are several ways to evaluate the preferences of Canadians for the format of future debates. In this section, we review several relevant topics asked in the pre-campaign DC module, the CES campaign period module and at the end of our focus groups. We focus in particular on questions about leaders’ and party participation in the debates, the moderator’s role, as well as the number and timing of debates in the future.

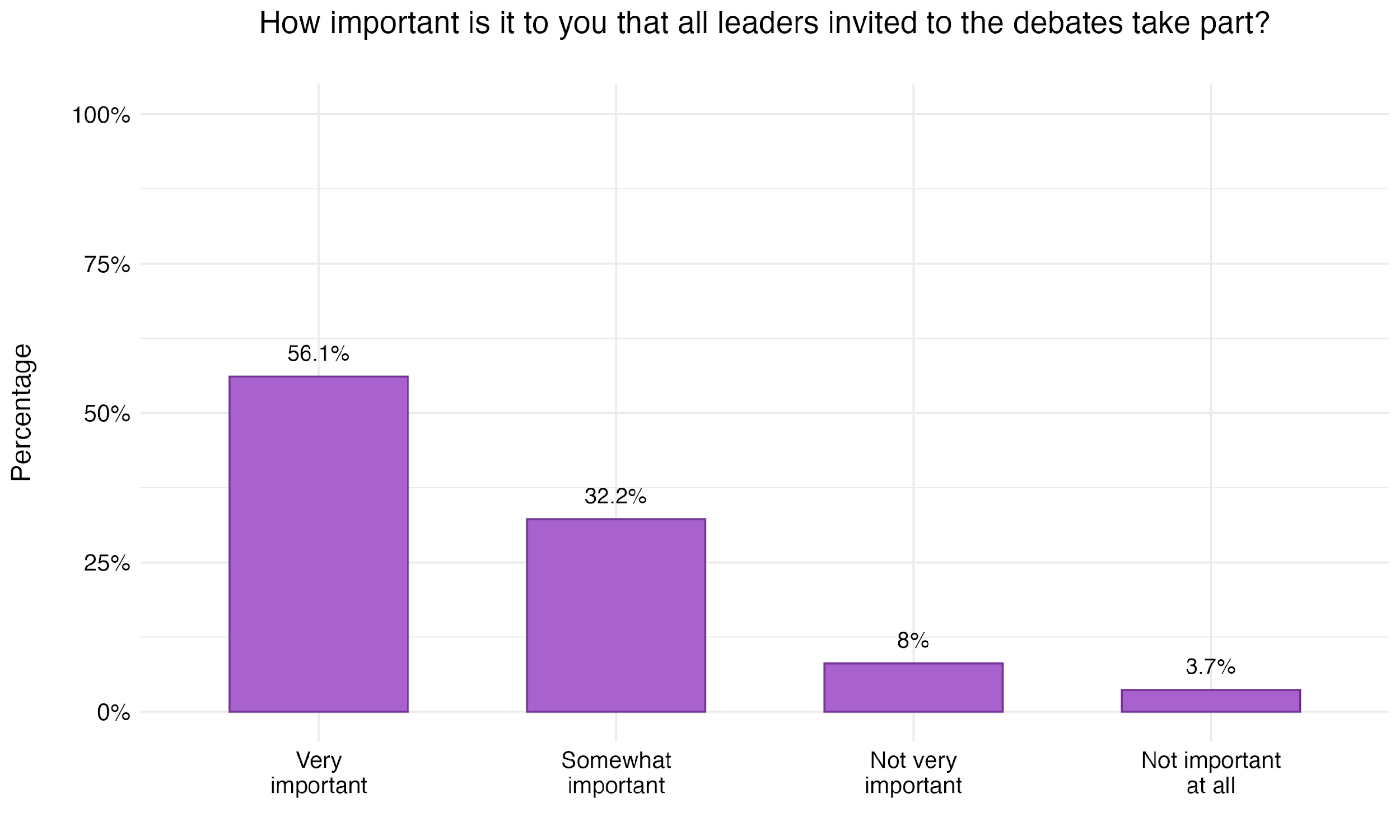

Leader Participation

We asked CES respondents about the importance of all leaders taking part in the debates. A majority reported “very important”; almost 90% indicated all leaders participating was “very” or “somewhat” important (Figure 32).

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

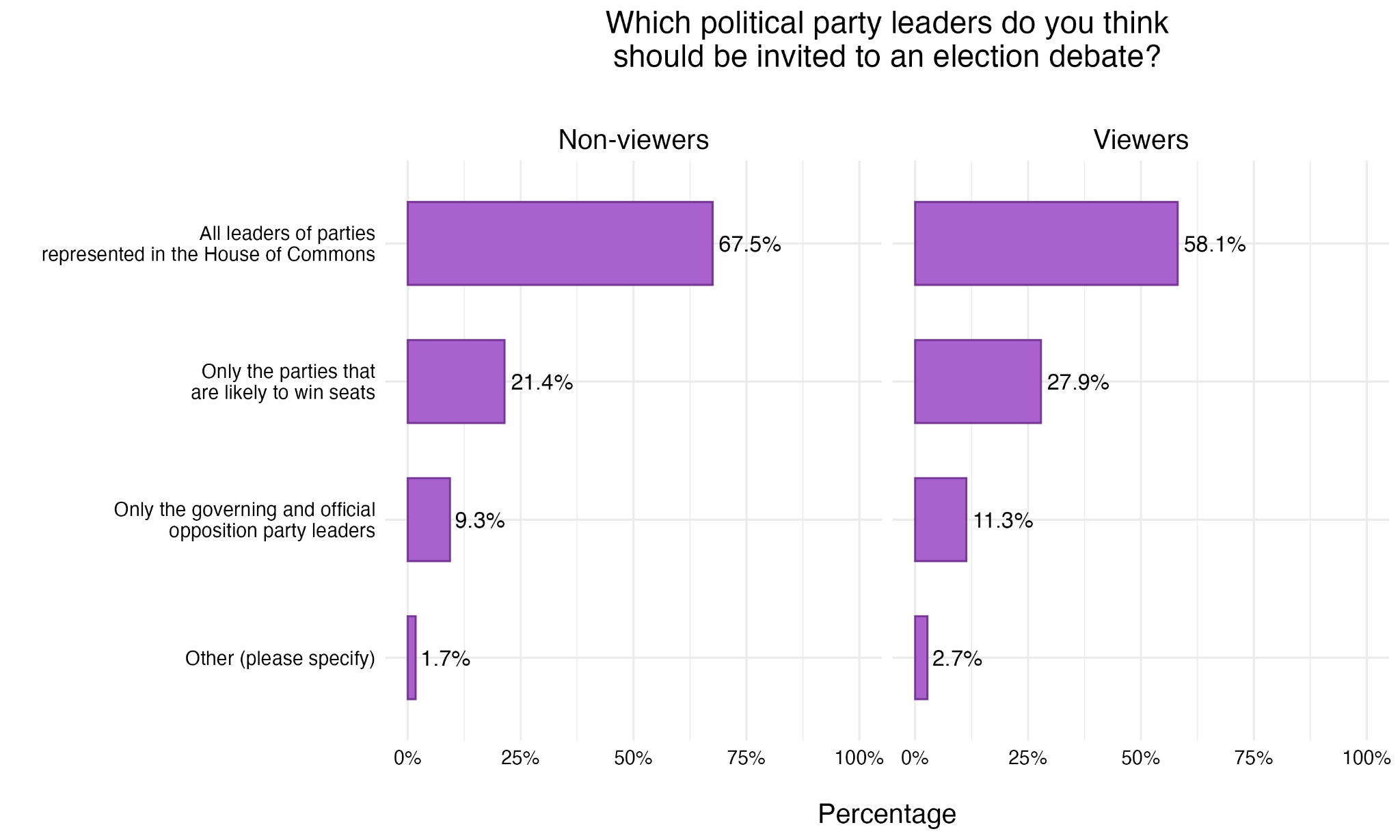

Respondents also weighed in on who they think should participate in debates. When given the option of the leaders of all parties in the House of Commons, parties likely to win seats, and only governing and official opposition parties, strong majorities of both non-viewers and viewers wanted all leaders of parties represented in the House of Commons. Some might think having so many party leaders crowds a stage, but a majority of both debate viewers and non-viewers thought all party leaders with House of Commons members should be present. Interestingly, the support for that among debate viewers was slightly lower. There was little support for limiting participation to those in the governing and official opposition.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

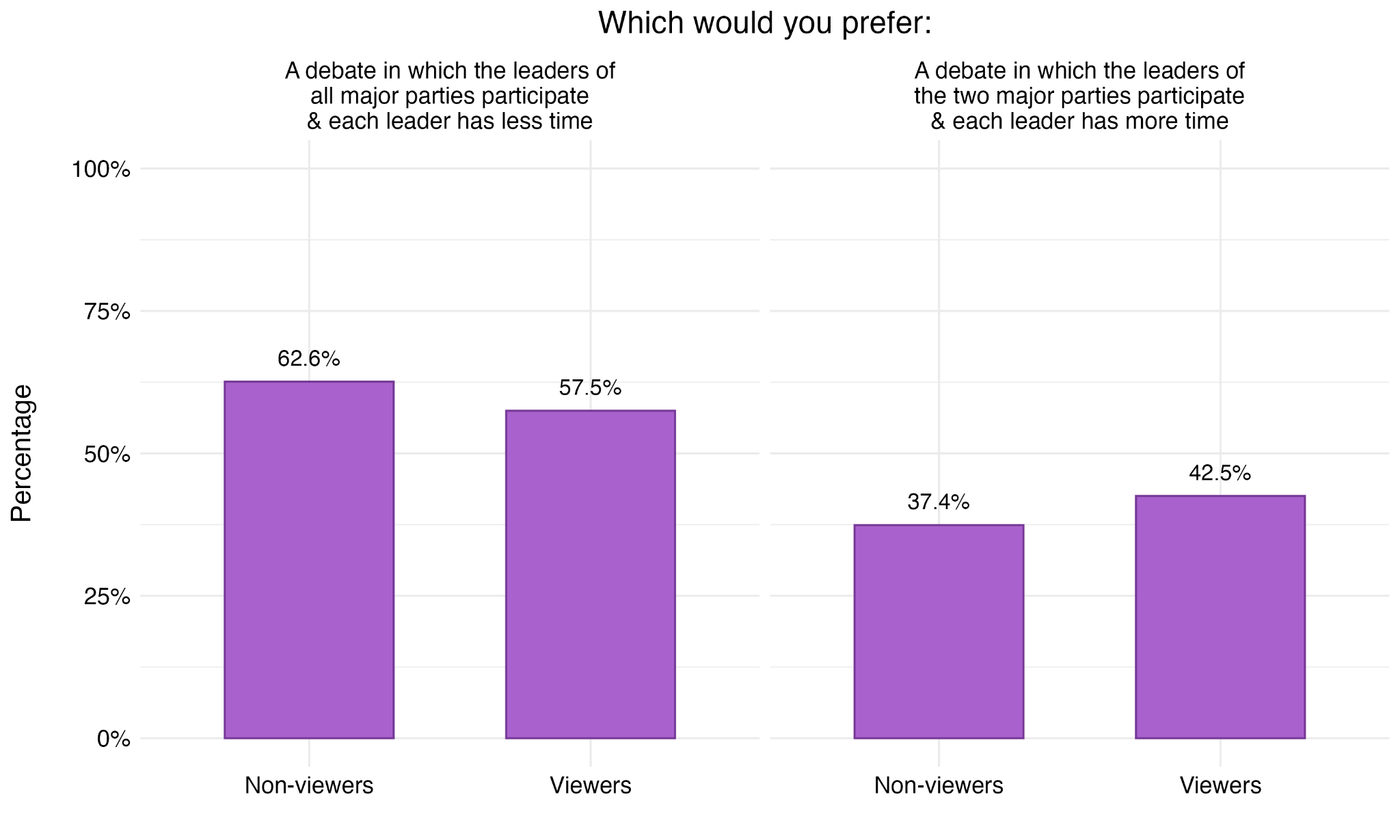

This more inclusive view of party participation is reinforced when respondents were asked a more clear trade-off question between having more leaders participate with less speaking time each, or fewer leaders with more time for discussion. Both viewers and non-viewers prefer that all leaders participate (Figure 34), but those who watched the debates expressed significantly more preference for a debate between the two major party leaders where each has more time to speak.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

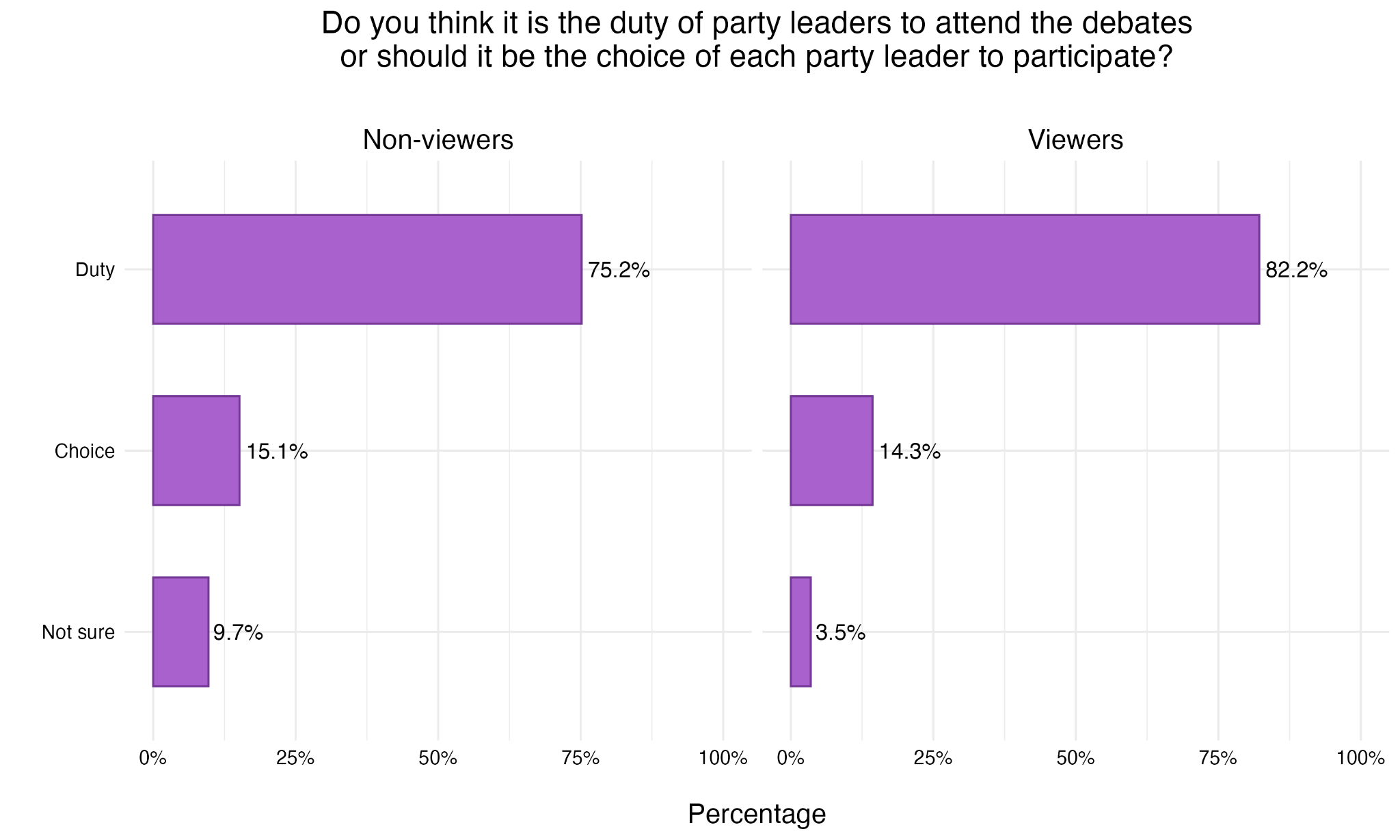

Respondents also indicated, overwhelmingly, that they thought it was the duty of party leaders to participate in these debates when invited (Figure 35).

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

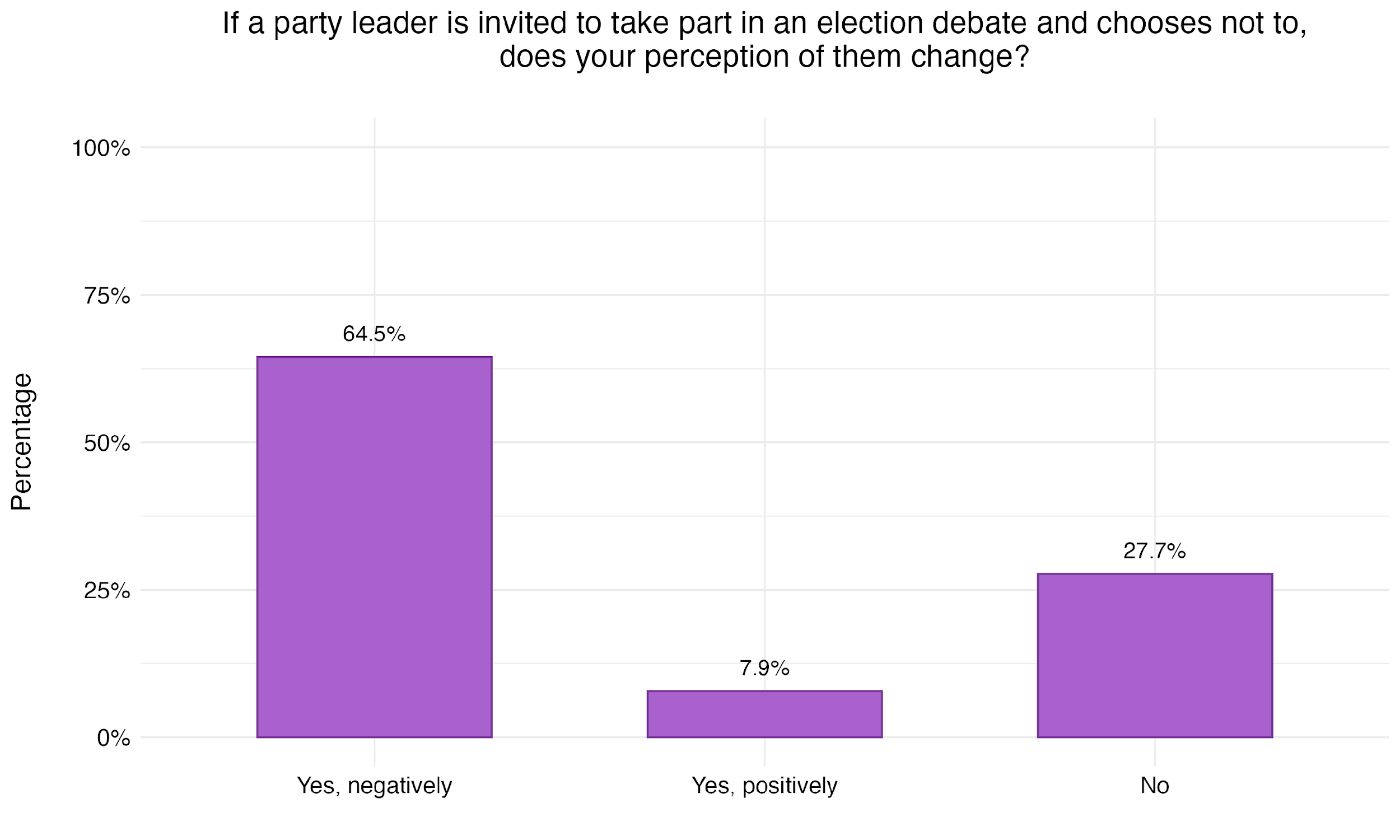

We also asked CES respondents about how not participating in a debate would affect their views. Results indicate that leaders who do not take part would be perceived more negatively (Figure 36), and that it could impact vote decisions (Figure 37), although to a less dramatic extent.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

The overwhelming view that emerges from the CES data is that Canadians expect party leaders, especially those of parties in the House of Commons, to participate in debates, and that when invited, leaders have an incentive and obligation to participate. The focus group data reflects these attitudes as well, but there were more mixed reactions. First, some people pointed to a lack of transparency in applying the rules, particularly in the case of the late exclusion of the Green Party, which some went so far as to judge as arbitrary or undemocratic. After the English-language debate, some questioned the legitimacy of the Bloc Québécois taking part, while others felt it was important to be able to reflect the diversity of provincial realities. It was also difficult for participants to agree on the number of debate participants. Having four leaders on stage seemed ideal to ensure a reasonable speaking time for each or to avoid complicating moderation, but a few respondents indicated a preference for more inclusivity. Some argued that smaller parties could benefit from greater visibility.

“I don't necessarily agree that the Greens not being there is the right thing, but it was a lot to handle with the four.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Le fait d’avoir exclu le Parti Vert [...] vient un peu brimer le discours politique ou le choix que la population pourrait avoir [...] Je trouve ça un peu décevant.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

“I did like having the Bloc Québécois there [...] but in some ways I feel like that should be every province.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

Moderation

In the pre-campaign DC data, we gathered opinions about types of moderation strategies. Figure 38 shows that all moderation strategies were supported by a majority of respondents. The strategy that was least popular was cutting microphones, but still 69% were in support. It appears that Canadians support, in principle, having specific steps taken during debates to ensure that people can be heard and that the information being shared is truthful.

Source: DC (2025), LDC Module (Weighted)

During the campaign, questions were also asked in the CES of debate viewers and non-viewers about their preferences for moderator fact-checking behaviour during debates (Figure 39). While both groups preferred that moderators took charge of correcting false information, there was a difference such that those who had watched the debates were more amenable (29%) to leaving the task to other leaders. Non-viewers, on the other hand, were most supportive (86.3%) having a moderator interrupt to correct false information.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

A whole section of focus group discussion was dedicated to talking about the moderators. Regarding the tone used by the moderators, the moderator of the English debate, Steve Paikin, was described by focus group members as polite and composed in his interventions, which many perceived positively. According to focus group participants, the fact that he was not prominent during the discussion allowed the candidates to be more in the spotlight. On the other hand, others would have liked him to be firmer with the leaders to end interruptions. Some found him disorganized in remembering whose turn it was to speak.

“Oh, I think he did wonderful tonight. I mean, it's a very difficult job to try to kind of manage everything that was going on. I thought his questions were good. They were direct. And sometimes the leaders kind of did get kind of carried away, kind of speaking over each other, but he was really good at reeling them back and respectfully”– Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Now Steve is very level-headed and calm, so it's nice to have that kind of person, not anyone who's going to rile anyone up. The moderator was exactly that. He was a moderator, didn't stand out. He was just good.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Honestly, he's not doing the best job, it's very unorganized, he keeps forgetting who was trying to speak.” – Participant in the English Chat #1

For their part, French-speaking respondents were unanimous in their satisfaction with journalist Patrice Roy's moderation. Although one participant noted that he had raised his voice unnecessarily on one occasion, this remained an isolated incident. It was mentioned that he seemed in control and could bring the leaders back to order, although a debate can sometimes become more difficult to follow when politicians cut each other off.

“Le modérateur semble avoir l'expérience donc il gère bien la discussion malgré la cacophonie.” – Participant in the French Chat #1

“Il y a comme crié fort, il pointait, puis il avait haussé le ton. Puis là j'étais comme bon oh là tu sais, c'est comme s’il c'était emporté.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #2

In both the French and English debates, participants agreed that the moderator seemed neutral, and the leaders were treated fairly and respectfully. Some noted differences in the amount of time given to each leader but conceded that this could depend on the number of questions received, including one-on-ones and interruptions when a participant went off-topic.

“He remained neutral. As far as his political opinion goes, which is what I think should happen.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Je crois que [Patrice Roy] a été dans les limites du possible objectif, à égale distance de chacun des participants.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #2

“I believe they are now [being treated fairly], but earlier on PP was interrupting people a lot. Singh interrupted a bit too earlier on. I think the moderator became a bit more strict.” – Participant in the English Chat #2

“I think someone mentioned this before, that a lot of the questions and the rebuttals were being directed to certain candidates. So I think it makes sense that some of the speakers did have more time than the rest because there were certain speakers they were focusing on more.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

In the French debate, participants felt that Patrice Roy's questions were appropriate, concrete and within the allotted time, and he knew how to prompt the leaders to go further in their answers. The lack of prompting was a criticism levelled at the moderator of the English debate, who some felt did not put enough pressure on the leaders to answer the questions posed. Some participants in the English focus groups had also watched the previous day's French debate and had noticed that the questions seemed better structured and more informative as the moderator did more contextualizing.

“J'ai trouvé Monsieur Roy très allumé ce soir. […] Il revenait avec les bonnes questions pour aller un peu plus loin avec les candidats.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

“They should have one segment where it's ordinary Canadians posing relevant questions and then having the moderator forcing them to answer the question, not beat around the bush.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

“The question, I think, was touched upon a bit, but one thing I noticed in the French debate was that the questions were really specific and had a bit of background info, and for the questions and the responses here, we didn't really see that.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

Considering more specifically the ideal role of a moderator, the participants overall seem to judge a good moderator as a “referee” who doesn’t dominate the debate but keeps it focused on the issues at hand, is respectful, and ensures that it is informative and useful for voters. This means intervening quickly when interruptions persist and even cutting off microphones if necessary. They must be alerted to attempts by certain candidates to bypass questions and insist on clarification. To ensure the smooth flow of the debate, a good moderator must manage speaking turns and handle time effectively. Although not everyone agrees on whether this is the moderator’s responsibility, some would like to see them step in to correct information.

“I think the role of the moderator should be to ask fair questions, but to make each candidate answer the question because a lot of them just dodge around it […]” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

“[The moderator should] not be afraid to cut people off. [...] Be strict with timing and just making sure everyone gets their say.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Quand il y avait des mensonges, j’avais envie de crier ‘Tu peux-tu lui dire que ça n’a pas d’allure ce qu’il vient de dire?’ Mais c’était pas son rôle.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

Many focus group participants would have liked to see some form of fact-checking incorporated into the debate to help voters discern what the leaders were saying and reinforce the confidence and quality of the debate. Indeed, in the French and English debates, some mentioned contradictory numbers (e.g., the number of homes built) that were confusing due to a lack of clarification.

“I would love if a fact checker [could] post if the statements the leaders state are in fact true. There are certain facts that I know I will have to look up afterwards instead [of] just believing them.” – Participant in the English Chat #2

“On aurait dû avoir un élément de vérification de faits. Je pense qu’il y a eu une fois où j'ai remarqué que Monsieur Roy a corrigé le tir. Mais ce qui n’a pas aidé aussi, c’est que Monsieur Carney, avec son français qui n’est pas terrible, des fois il me met des chiffres […], mais je n’arrivais pas vraiment à saisir. ” – Participant in the French Focus Group #2

There was less consensus on who should be responsible for fact-checking. Some felt the moderator could play this role, as was partially done in the French debate, but others thought this was not their role. Some suggestions included a behind-the-scenes team or journalists could also set up, for example, an on-screen box or scrolling strip for real-time corrections or clarifications, post-debate resources, or platforms for consulting party positions.

“I think the moderator should be responsible for it, just because I saw the French debate and he was kind of doing that in his own way, when he was providing that background information and giving context to the questions […].” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

“Not sure if the moderator would be able to do this while moderating the debate. But, a ticker [...] might sway them not to exaggerate any facts.”– Participant in the English Chat #2

Despite this, there are challenges to be considered, whether it is keeping up with the pace of the debate for verifications, distractions if too much information ends up on the screen, or ensuring a certain neutrality in fact-checking. In one of the discussion groups, some people believed that citizens also have a personal responsibility to inform themselves.

“Moi je pense que ce n’est peut-être pas son rôle nécessairement à lui [le modérateur], mais après ça, je pense, ça va être aux gens de faire une recherche puis de consulter Radio-Canada.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

Format

One of the key decisions about debate format is whether to allow leaders to have a free-flowing conversation or whether the moderator should have more control of the topic and speaking time of each leader.

During the campaign period, CES respondents were asked specifically about this trade-off. We asked whether there was a preference between free-flowing conversations around topics initiated from moderator questions and more controlled speaking times for answering questions that ensured fairness across leaders. Overall there is a preference across viewers and non-viewers for a more natural conversation, with little difference across viewership (Figure 40). That said, there is a significant minority (about 41-43%) who prefer strict time segments, but the difference is small. This suggests divided views among the Canadian public.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Debate Topics

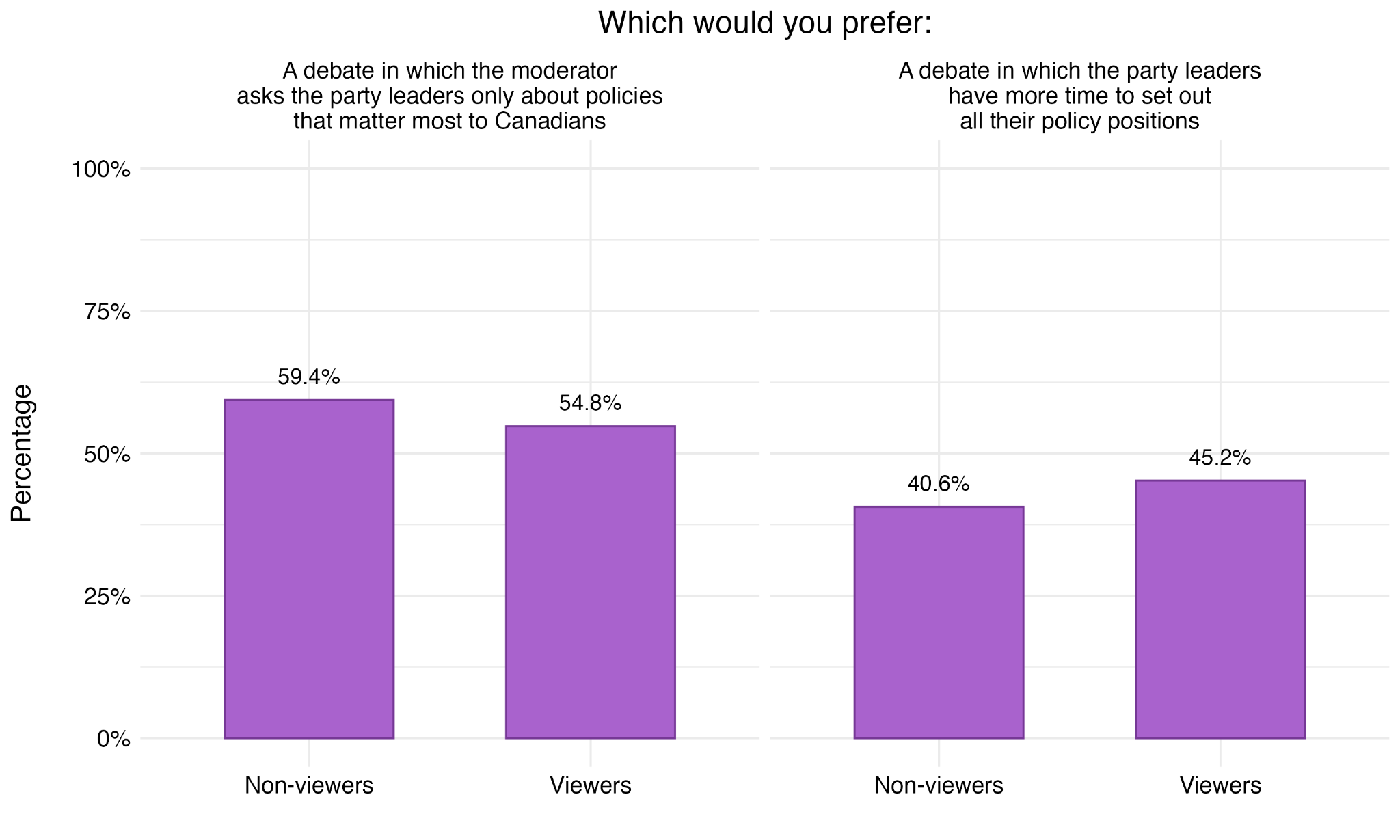

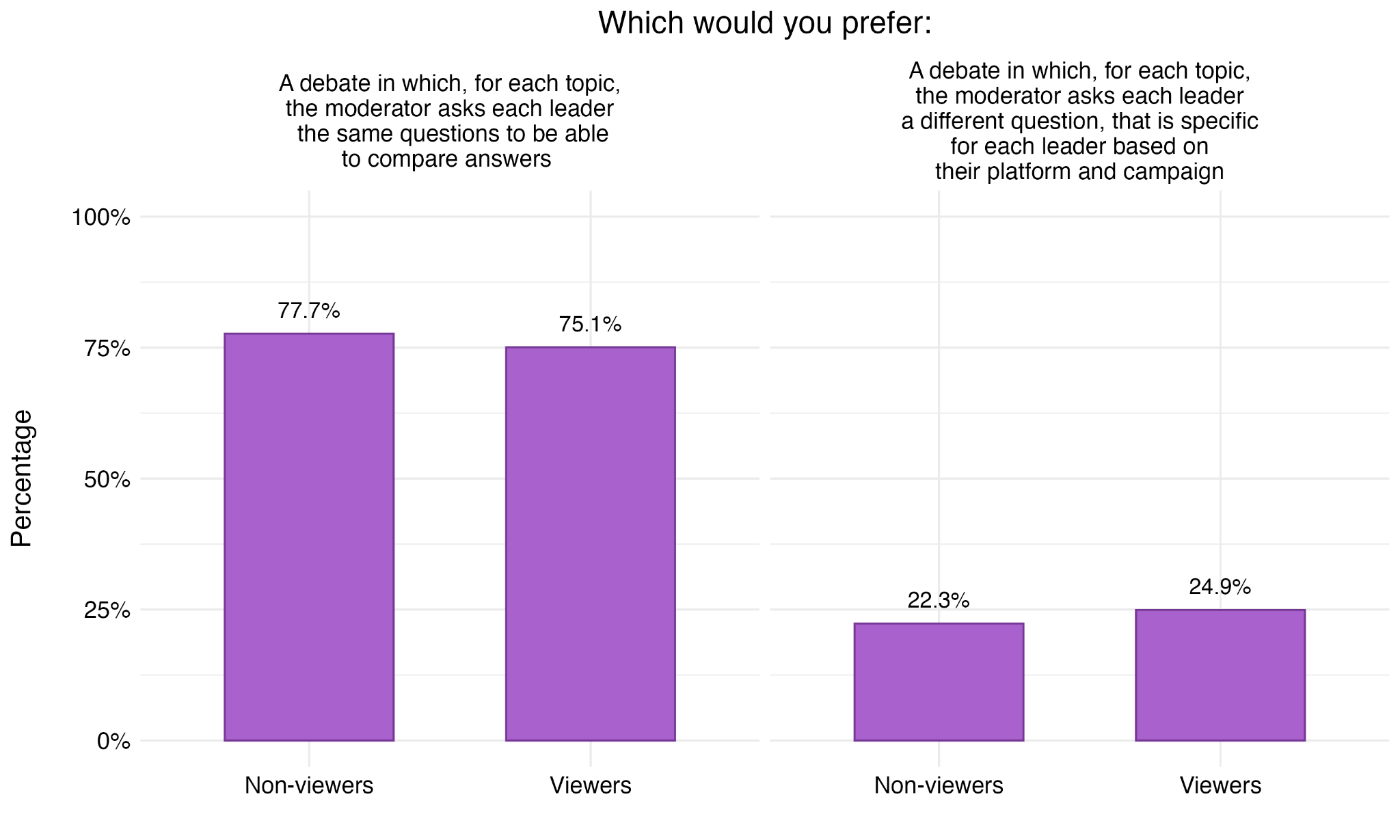

Canadians seem to have a preference, although not overwhelming, for debates focusing on issues that matter to Canadians, rather than party platform policies (Figure 41). This varies a bit between those who did and did not watch the debates, such that those who watched are more likely to prefer asking about platform policies (significant at p=0.051). When it comes to the types of questions asked, there is a preference for standardizing across leaders rather than reflecting specific party platform content (Figure 42). On this last point, there is little variation across viewership.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Debate Format

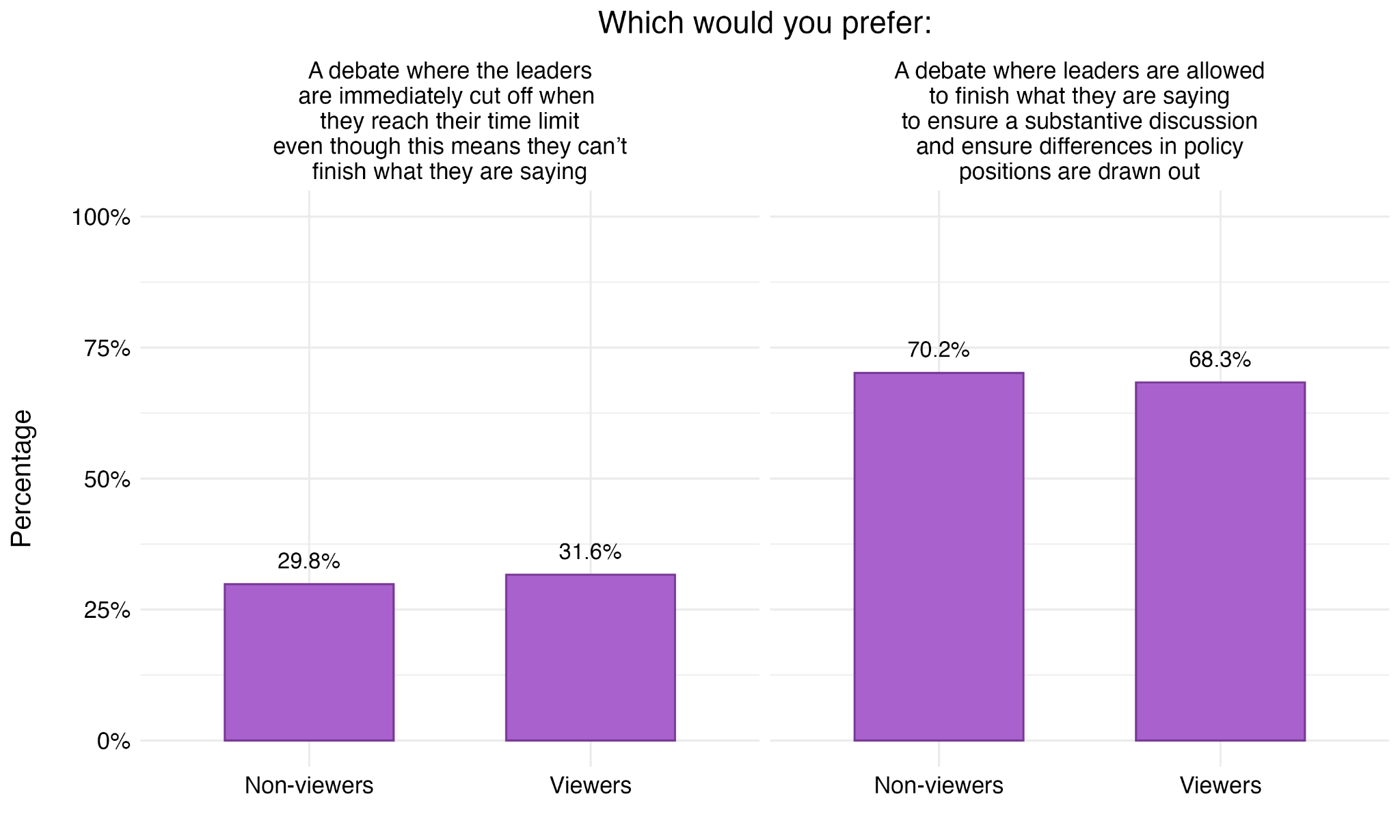

After the debates were held, the CES probed preferences over cutting off leaders. It is notable that there is not a lot of difference in responses between viewers and non-viewers. But similar to Figure 40 where Canadians expressed a preference for more free flowing conversation, we see in Figure 43 that a strong majority of respondents want party leaders to be able to finish what they are saying.

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

Scheduling the Debates

During the focus groups, we asked participants their thoughts about the location of the debates. In the case of the French-language debate, participants had no objection to both debates being held in Radio-Canada's studios in Montreal. They stressed the relevance of keeping at least the French-language debate in Quebec. It was seen as a neutral and professional location.

“Je trouve que c'est quand même une marque de considération que le débat français soit enregistré au Québec. ” – Participant in the French Focus Group #2

There did not seem to be much reaction to location for the English debate either, although two participants would have considered holding the debates in other provinces to avoid the perception of bias.

“I think we should have, you know, one [debate] in the West and one maybe in the Maritimes and one in, you know, Quebec-Ontario area to spread it around. Having them both in the same [place] was a little bit biased in my opinion, and they should think about that in the future.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

We also asked about the specific time of the debates. Our prompt was: “We’ve heard before that 7pm on a weekday is the ideal time for a debate. But Canada has 6 time zones, so timing will vary across the country. What do you think is the ideal time for a debate, knowing that it will be 3.5 hours earlier in BC than in NFLD?” It is difficult to satisfy all Canadians because of time differences, an issue recognized by many. In Western Canada, the start of the debate conflicted with work schedules or suppertime, while in Eastern Canada, the end of the debate was considered too late, especially for a weekday. To improve broadcasting, some would have preferred a weekend broadcast or even considered a delayed broadcast, given that the debate did not involve live interaction with the audience. On the other hand, the last-minute rescheduling of the French-language debate due to a Montreal Canadiens hockey game was more or less well-received, although communication was perceived as inadequate. However, participants noted that the availability of recordings, delayed broadcasts, and media summaries helped mitigate the issue.

“That was a great time for us here to start at 8:00. But if it was the 4:00 or 5:00, that definitely would have interrupted my day, and I probably wouldn't have sat down to watch if I was on the West Coast of Canada.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #2

“Faut quand même se rappeler une chose, c’est que ça n’a pas besoin d’être en direct. [...] Ça aurait bien pu être enregistré puis diffusé aux heures suivantes.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #2

Number of Debates

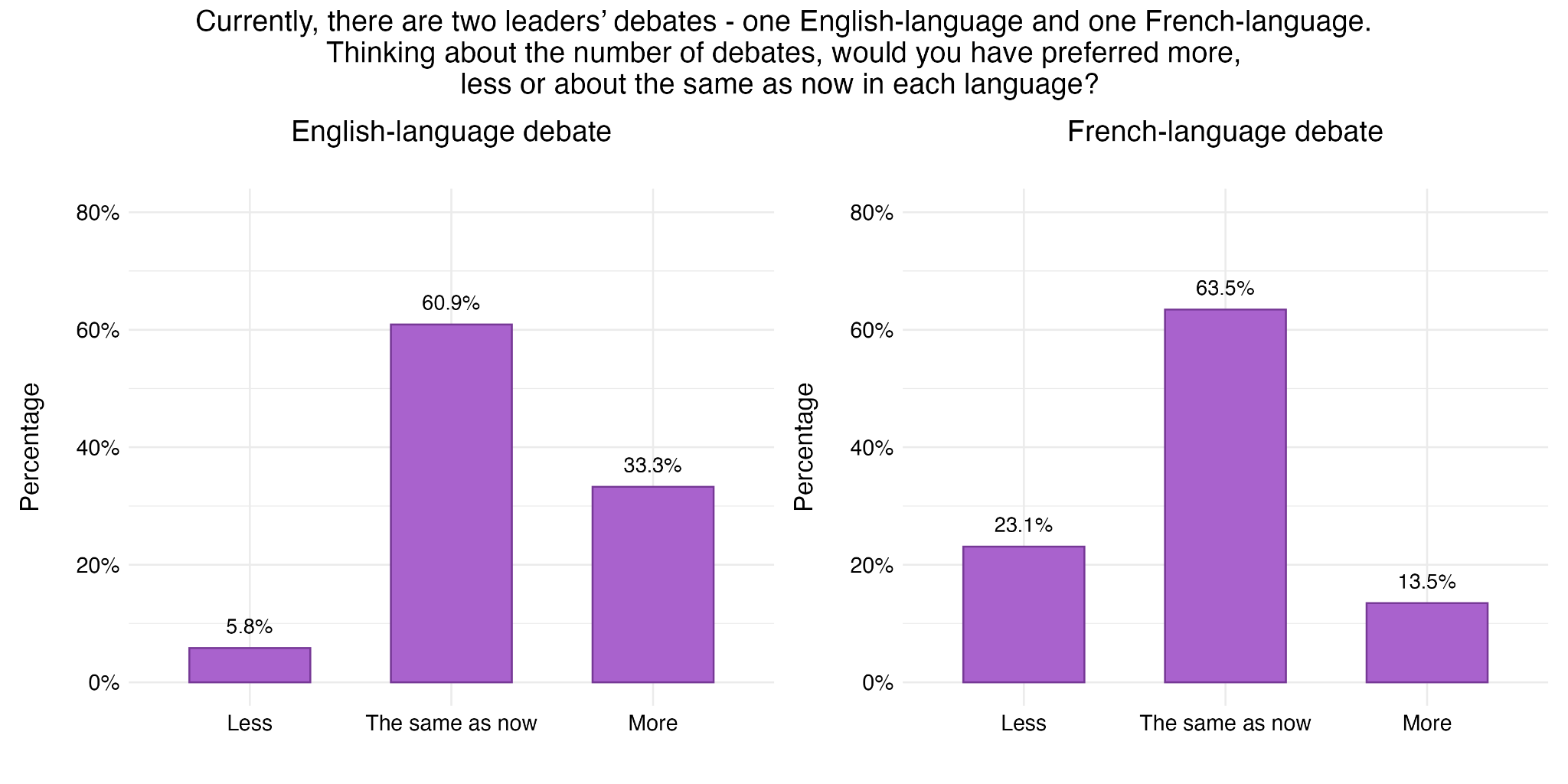

We also inquired about preferences over the number of debates in our campaign-period survey. There was considerable support for keeping things as they currently stand, with one official debate in each language (Figure 44).

Source: CES (2025) Campaign Period Survey (Weighted)

We asked similar questions of the focus group respondents. While some people considered the possibility of an additional debate addressing different issues at the beginning and end of the campaign, the current number of debates seemed sufficient for many participants. Some mentioned this would be irrelevant in a short election or when the parties do not present a clear platform. Also, while getting information during debates can be helpful for new voters, many felt it probably does not change the voting decision for most people.

“I do think I would like to at least see one more in English [...]. I think max four. I don’t think we should ever go over that. [...] it can just also confuse Canadians, I think, before voting, especially for young voters.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

“Ça dépendrait de la durée de la campagne [...]. Je veux dire que le format ne soit pas tout pareil entre les deux débats, pour moi ce serait intéressant.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

Many people seemed keen to see members of parliament or riding candidates debate each other. This, they thought, could give them better insight into how their regional interests would be represented in the House of Commons. On the other hand, concern remained regarding the time and resources that would be put into the organization so that these debates could be televised. Other risks raised were that these exchanges might be unfair, depending on the occupation or background of the debate participants, or that some might stick too closely to party lines. Under such conditions, some doubted that additional debates would be enlightening.

“I also like to look into my MP when I'm voting because I feel like that's the person who represents my regional interest in Ottawa.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

“If there were MPs I was interested in or if like it was a tight race [...] I think I would want to watch them. [...] But I think it would just be a lot of debates going on at once.” – Participant in the English Focus Group #1

“C’est un idéal, mais en autant que tout le monde soit là pour débattre, sinon ça devient quelque chose qui n’est pas un bon investissement pour ceux qui veulent vraiment se faire une opinion.” – Participant in the French Focus Group #1

Comparing Findings with 2019 and 2021

To put the results from this study of the 2025 leaders’ debates into context, we can consider them in light of the findings regarding the 2019 and 2021 debates. The format of the 2025 study differs in some respects from the format of the other studies so the comparisons are not always direct comparisons, but we can comment on similarities and differences where they appear.

Pre-Debate Awareness

We did not ask people prior to the debate, but during the campaign period, if they had heard or read anything about the upcoming debate. In 2019 and 2021, the results showed that awareness was not high - about 39% were aware of the debates in 2019 and 40% of French-speakers and 26% of English-speakers in 2021. But our results show that there was an overwhelming expectation in 2025 that debates would occur - over 85% of English and French speakers, surveyed over a month before the campaign began. Our results also suggest that debates are considered to be important for Canadians, and that importance is based upon the opportunity debates provide to get informed and to assess the leaders’ competence and/or characteristics, as well as to hear and learn about their policies.

Earlier studies found that rural Canadians were less aware and older Canadians more aware. While our study did not ask specifically about awareness of upcoming debates, we found overwhelming expectations that they would occur and this varied little across sociodemographic groups. Furthermore, when non-viewers were queried, only between 5% (French debate) and 10% (English debate) reported that forgetting or not knowing it was happening was the reason.

Debate Viewership

Our survey sugges ts 44.7% of English-speakers and 40.2% of the French-speakers watched at least one debate. If we look at language of the debate, 37.9% of French-speakers watched the French debate and 41.7% of English-speakers watched the English debate. In 2021, the numbers were 32 and 29%, respectively; in 2019 they were 43 and 39%. In terms of viewing versus not viewing, we found that age (older) and gender (men) were significant correlates of viewership, but that language was not, unlike the 2019 and 2021 results.

Evaluation of Debates

The best data we gathered about debate evaluations come from the focus groups, conducted immediately after the debates. Individuals in the groups indicated general satisfaction with the events, though this is harder to compare with previous reports.

We can consider responses in the CES more directly, where viewers rated their learning from the debates on the positive side (closer to “learned a lot” than “learned nothing” but this was more so for the English debates (Figure 20). In 2019 and 2021 majorities of respondents indicated the debates were “informative” - the level fell for the French debates in 2021 but increased for the English debates. A bare majority also indicated the English debates were “dull” in both election years.

We also gathered information about the moderators in the CES. The ratings in 2025 suggest that opinions about the moderators’ effectiveness in ensuring a respectful debate and being fair to party leaders was quite varied among respondents, with a slight advantage for the French moderator. The ability of moderators to post neutral questions was seen more positively overall, but again the distribution of responses was quite wide (Figure 17). Among non-viewers, very few reported hearing anything about the debate moderators - 14% for the French debates and 9% for the English debates. Opinions of the moderators among these people, with only second-hand knowledge of how the debates were run, was slightly lower. The moderators seemed to receive better reviews in 2019 and 2021, though caution is warranted given the relative positive “live” evaluations we received during focus groups.

Impact of the Debates

Because the 2025 study did not have the same design as the ones conducted in 2019 and 2021, we cannot make direct comparisons about the impact of the debates on individuals. However, we can comment on how our findings relate to the earlier ones. Our respondents indicated that they learned about leaders (their character, policies and platforms) from the debates. The biggest effect was for character in the English debate. The 2025 data also reveal that debate viewers are more able to rate parties and leaders (fewer don’t know responses). Overall, these findings for the 2025 debates seem comparable to the findings for 2019 and 2021, where viewership was associated with knowledge of party platforms in 2019 and improved ability to rate leaders in 2021.

Public Preferences about Future Debates

The only point of comparison with respect to debate format preferences has to do with cutting off speakers. We found some support for moderators taking an active role - interrupting if leaders talk over each other and even cutting off microphones. However, we also found significant support for taking steps to ensure that debates include substantive discussions and inform viewers of policy positions. This trade-off is reflected in the 2021 data, which showed a small majority preferred cutting off discussion even if someone could not finish what they were saying.

Appendix

Appendix A: Pre-Campaign Democracy Checkup LDC Survey Module

pre_debate_module_1 Do you expect that there will be leaders’ debates in advance of the next federal election?

- Yes (1)

- No (2)

pre_debate_module_2 How important is it to you that televised debates take place during an election campaign?

- Very important (1)

- Somewhat important (2)

- Not very important (3)

- Not important at all (4)

pre_debate_module_3 In your own words, can you tell us why you think televised debates are ${e://Field/pre_debate_module_2_text} during an election campaign?

pre_debate_module_4 How important is it to you that all leaders invited to the debates take part?

- Very important (1)

- Somewhat important (2)

- Not very important (3)

- Not important at all (4)

pre_debate_module_5 If a party leader is invited to take part in an election debate and chooses not to, does your perception of them change?

- Yes, negatively (1)

- Yes, positively (2)

- No (3)

pre_debate_module_6 In your opinion, what does deciding not to participate in a debate convey to the Canadian public?

pre_debate_module_7 If a leader refuses to participate in an election debate, would it influence your decision to vote for their party?

- Yes (1)

- No (2)

- Unsure (3)