Federal leaders’ debates: How Canadians responded to the 2021 debates and what they want for future debates

- John R. McAndrews (University of Toronto)

- Aengus Bridgman (McGill University)

- Peter John Loewen (University of Toronto)

- Thomas Bergeron (University of Toronto)

- Thomas Galipeau (University of Toronto)

- Allison Harell (Université du Québec à Montréal)

- Daniel Rubenson (Ryerson University)

- Laura B. Stephenson (Western University)

January 5, 2022

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Summary of findings

- 3 Methodology

- 4 Findings

- 5 Comparing the 2019 and 2021 findings

- Appendix - Supplementary Report on Focus Groups

1 Introduction

We were engaged by the Leaders' Debates Commission to conduct a comprehensive examination of the public's response to federal leaders' debates. Our aim was two-fold: first, to investigate how the public evaluated and reacted to the two Commission-organized leaders' debates held during the 2021 federal election campaign; and, second, to explore the public's preferences for how such debates should be conducted in future. We did so by conducting and analyzing three broadly representative online surveys of Canadians and by collecting and analyzing approximately 12 million tweets from before, during, and after the 2021 election.

Our report serves as both a companion to—and an extension of—our 2019 report to the Commission. As in 2019, we report here on the public's awareness, viewership, discussion, and evaluation of the leaders' debates. Like our 2019 report, we also leverage a panel survey design to estimate the impacts that the debates had on citizens' political engagement, knowledge, judgements, and behaviour. We then build on our work by diving deeper into the public's preferences for how debates should be conducted—examining what citizens think should be the goals of such debates, who should participate in the debates, how the debates should be moderated, what formats should be used, and when the debates should be scheduled. The result is—we believe—the most comprehensive and up-to-date portrait available of what Canadians want for their federal leaders' debates.

2 Summary of findings

We find that the 2021 debates attracted a significant public audience, though somewhat smaller than in 2019. Majorities of both French debate viewers and English debate viewers agreed that the debates were informative—reserving their most favourable evaluations for how each debate was moderated. We also find that the debates generated several positive outcomes. They contributed, for example, to increases in citizens' political interest, consumption of news about the federal election, and trust in the federal government.

Looking to the future, we find that Canadians—within the context of a single-debate framework—tend to prefer a multi-topic debate that provides for both wide and equal leader participation and an assertive role for the moderator. Having said this, we also find that the public has an appetite for more than one debate in each official language. This possibility of multiple debates also gives rise to public interest in other, more specialized forms of campaign-based public events outside the recent norm—such as public meetings between leaders and citizens, issue-specific debates, and regionally-focused debates.

3 Methodology

3.1 Survey research

We conducted three online surveys of Canadians. The first wave was conducted between September 2 and September 8—ending just before the start of the French debate at 8 pm Eastern on that day. This first wave sample was constructed from online panels using quotas for region (Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, and the West), official language, gender, and age (18-34 years, 35-54 years, and 55+ years)—as well as flex quotas for gender and age within region.

By design, the second wave was a recontact of participants who completed the first wave. The sampling for this second wave was done in a convenience framework from among these first wave participants—along with a quota for official language. As described in Section 3.1.1, the purpose of this recontact design was to help identify within-individual change in key political attitudes and behaviours between the period just before and just after the debates.

The second wave was fielded between 10:35 pm Eastern on September 8—just after the French debate ended—through to September 16. The fielding proceeded in two stages. The first stage took place during the 24-hour interval between the end of the French debate on September 8 and the beginning of the English debate on September 9. During this first stage, the survey asked only about the French debate (since the English debate had not yet happened) and only French-speaking participants from the first wave were invited to complete it. A total of 97 French-speaking participants completed during this initial stage. The second stage of fielding began just after the end of the English debate at 11 pm Eastern on September 9. In this second stage, the battery of English debate questions was added and the survey went live to English-speaking recontacts from the first wave.

The third and final survey wave as a fresh cross-section of Canadians. It was constructed from online panels using the same quota-based sampling procedure employed in the first wave. The chief purpose of this third wave was to provide a detailed snapshot of Canadians' preferences for future debates. It was conducted between November 24 and 29.

To further promote the representativeness of these three online samples, we created survey weights for each survey wave. In the case of each wave, the sample was weighted using an iterative proportional fitting algorithm based on national population estimates for province (region, in the case of the third wave), age category, gender, 2019 voter turnout (2021 turnout, in the case of the third wave), and whether or not the participant was born in Canada.Footnote 1 Note, however, that we report unweighted results for those questions that were administered only to debate viewers (e.g., their evaluations of specific aspects of the debate) because there are understandably no population-level parameters for the demographic composition of debate viewers.

Following standard response quality checks and weighting, the total sample sizes of Waves 1, 2, and 3 were N=2002, N=995, and N=488, respectively.

3.1.1 Using within-participant change to estimate the impact of debate viewership

As noted above, the aim of recontacting Wave 1 participants in Wave 2 was to be able to administer an identical set of questions to the same individuals. In so doing, we can compare their responses from just before the debates to their responses just after the debates. This allows us to estimate the impact of the debates, which we report in Section 4.6.

We use a regression framework to estimate the impact of the debates by regressing the within-individual change in each outcome of interest on a binary indicator that takes a value of 1 if the participant watched either the French or English Commission-organized debates and 0 otherwise. We also include in the model additional covariates for gender, age in years, a 3-category measure of education, and income. In this framework, the regression estimate of the impact of debate watching captures the difference in the between-wave change in the outcome of interest between those who watched a debate and those who did not.

In Section 4.6, we report the results of this regression analysis for 26 different democratic outcomes, ranging from political interest to knowledge to vote choice. The manner in which the within-individual change was operationalized varied by outcome and is detailed in Table 1. All regression models were estimated using ordinary least squares.

| Figure Number | Name of outcome (DV) | How the outcome was operationalized |

|---|---|---|

| 23 | Change in interest about federal election | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 7 on a 0 to 10 scale. |

| Change in issue mentions | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 3 on a 0 to 6 scale. |

|

| Change in news consumption about federal election | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 1 on a 0 to 4 scale. |

|

| Change in discussion of federal election | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 0 on a 0 to 3 scale. |

|

| Change in interest about politics generally | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 7 on a 0 to 10 scale. |

|

| Change in news consumption in general | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 3 on a 1 to 6 scale. |

|

| 24 | Change in knowledge of party promises | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 2 on a 0 to 10 scale. |

| Change in knowledge of current economic and social conditions | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 1 on a 0 to 4 scale. |

|

| Chance in confidence to make a good voting decision | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 7 on a 0 to 10 scale. |

|

| 25 | Change in ability to evaluate party leaders' traits | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 15 on a 0 to 20 scale. |

| Change in ability to rate all five leaders | Participants were coded as: -1 if they rated all five party leaders in Wave 1 but did not rate all five party leaders in Wave 2; 0 if they did not rate all five party leaders in both Wave 1 and 2, or if they rated all five party leaders in both Wave 1 and 2; 1 if they did not rate all five party leaders in Wave 1 but did rate all five party leaders in Wave 2. |

|

| Change in ability to rate all five parties | Participants were coded as: -1 if they rated all five parties in Wave 1 but did not rate all five parties in Wave 2; 0 if they did not rate all five parties in both Wave 1 and 2, or if they rated all five parties in both Wave 1 and 2; 1 if they did not rate all five parties in Wave 1 but did rate all five parties in Wave 2. |

|

| Change in ability to place all five parties on left-right scale | Participants were coded as: -1 if they placed all five parties in Wave 1 but did not place all five parties in Wave 2; 0 if they did not place all five parties in both Wave 1 and 2, or if they placed all five parties in both Wave 1 and 2; 1 if they did not place all five parties in Wave 1 but did place all five parties in Wave 2. |

|

| 26 | Change in leader ratings | For each participant, we first computed the absolute difference for each of their leader feeling thermometer ratings between Wave 1 and 2, and then we computed the average of these absolute differences. The original leader ratings were on a 0 to 100 scale. |

| Change in party ratings | For each participant, we first computed the absolute difference for each of their party feeling thermometer ratings between Wave 1 and 2, and then we computed the average of these absolute differences. The original party ratings were on a 0 to 100 scale. |

|

| Change in left-right placement | For each participant, we first computed the absolute difference for each of their party left-right placements between Wave 1 and 2, and then we computed the average of these absolute differences. The original left-right part placement scale ran from 0 to 10. |

|

| Change in best party to handle the most important issue | Participants were coded as: 0 if their answer in Wave 1 was the same as their answer in Wave 2; 1 if their answer in Wave 1 differed from their answer in Wave 2. |

|

| 27 | Change in political efficacy | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 1 on a 0 to 3 scale. |

| Change in satisfaction with Canadian democracy | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 2 on a 0 to 3 scale. |

|

| Change in trust in the courts | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 4 on a 1 to 5 scale. |

|

| Change in trust in the federal government | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 3 on a 1 to 5 scale. |

|

| Change in trust in the media | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 3 on a 1 to 5 scale. |

|

| Change in trust in political parties | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 3 on a 1 to 5 scale. |

|

| 28 | Change in intention to turn out to vote | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from certain to vote to not certain to vote; 0 if they remained either not certain to vote or certain to vote; 1 if they moved from not certain to vote to certain to vote. |

| Change in vote choice | Participants were coded as: 0 if their answer in Wave 1 was the same as their answer in Wave 2; 1 if their answer in Wave 1 differed from their answer in Wave 2. |

|

| Change in expected future engagement in non-voting forms of political engagement | Participants were coded as: -1 if they moved from above the Wave 1 median value to at or below the Wave 1 median value; 0 if they remained at or below the Wave 1 median value or remained above the Wave 1 median value; 1 if they moved from at or below the Wave 1 median value to above the Wave 1 median value. The Wave 1 median value was 0.333 on a 0 to 3 scale. |

3.2 Social media research

Twitter is the site of much Canadian political discussion. Candidates, party leaders, journalists, electoral management bodies, and many Canadians use Twitter to keep up to date with recent political developments and to share their perspectives on politics. Of the approximately 35% of Canadians who use Twitter, 46% of these users (16% of all Canadians) use the platform to get political information.Footnote 2

There are other social media platforms on which Canadians discussed the 2021 election. These include Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, Reddit, Tumblr, 4Chan, Gab, Rumble, Telegram, Discord, and many more. This report draws exclusively upon Twitter data given that it is almost entirely publicly available and accessible. Other social media sites may offer additional insights beyond those on Twitter, and further research should be done to evaluate the extent to which the findings on Twitter are reflective of the broader online community.

For this analysis, we use two Twitter data sources. First, we tracked a broad set of politics-related hashtags and keywords throughout the 2021 election—yielding a dataset of approximately 12 million tweets from two weeks before the writ period to two weeks after the writ period. In this group, we identified 84,560 individuals who consistently posted about Canadian politics on Twitter throughout the election. Second, we identified approximately 1.6 million likely Canadians based on their description and location and collected all tweets from them during the same period. We collected 265,835 accounts that actively tweeted on any subject throughout the election. This second dataset is more representative of the broader Canadian conversation on Twitter and allows insight into the extent to which Canadians use Twitter for politics and, of those, who commented on the debates. A full list of handles and hashtags tracked is available from the study authors upon request.

To help assess the content of tweets, we conducted a sentiment analysis using the Lexicoder dictionary (Young and Soroka 2012) for English-language texts, and a French-language translation of the Lexicoder dictionary for French-language texts (Duval and Pétry 2016). These tools identify a set of positive and negative word tokens that can be measured over a set of texts to classify those texts as generally negative or positive in tone. The proportion of positive to negative words allows the overall tone of a set of texts to be identified in an automated manner.

4 Findings

4.1 Public awareness in the run up to the debates

4.1.1 Overall awareness and across demographic groups

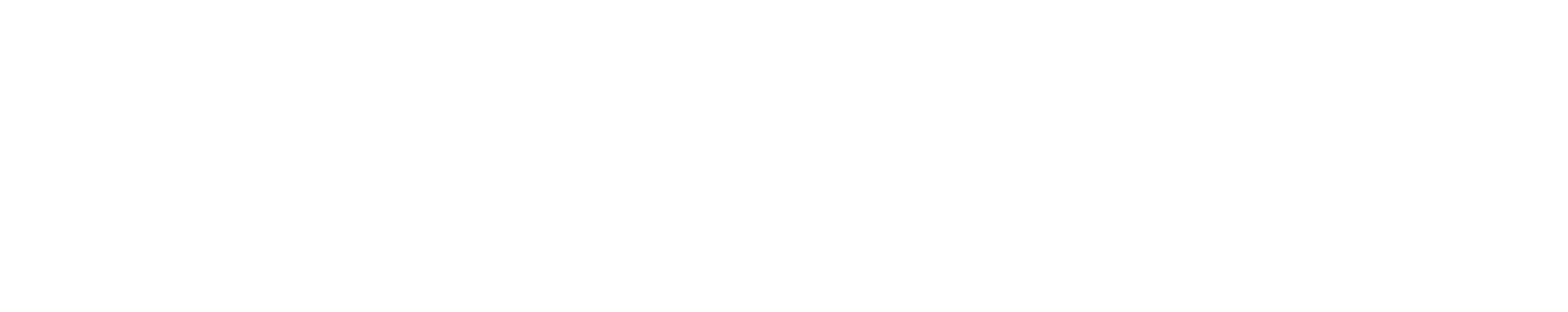

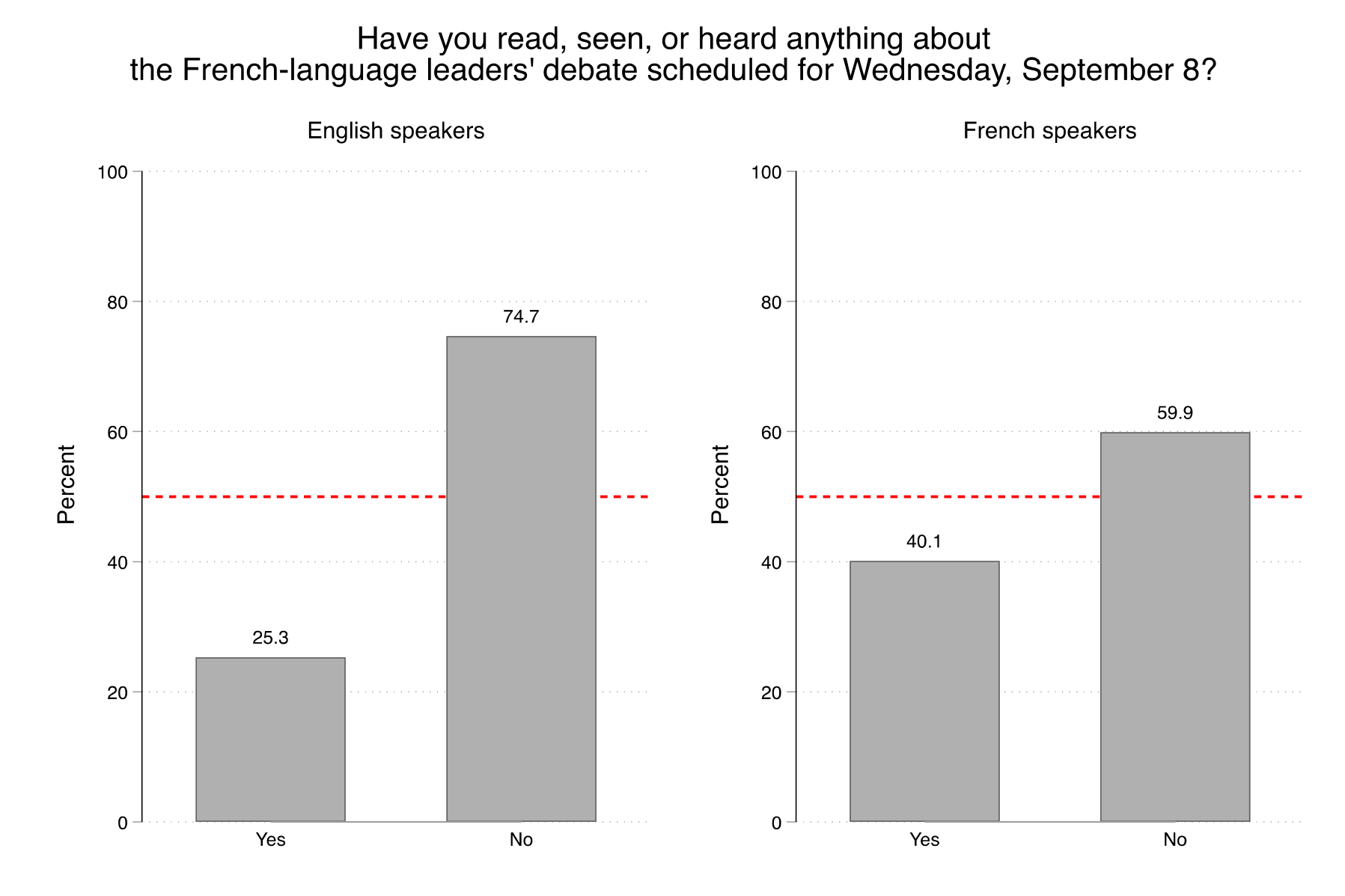

In the lead up to the debates, we asked participants in the first wave of the survey whether they were aware of each of the upcoming Commission-organized debates. Figure 1 presents the results for the September 8, 2021 French-language leaders' debate by participant language. Forty percent of French-speaking participants indicated that they had indeed "read, seen, or heard" something about the French debate; one-quarter of English-speaking participants said the same.

Figure 2 presents the results for the September 9, 2021 English-language leaders' debate—again by participant language. This time, 26% of English-speaking participants indicated that they had indeed "read, seen, or heard" something about the English debate, while 17% of French-speaking participants said the same.

We highlight two points with regard to pre-debate awareness. First, and not very surprisingly, the awareness of a debate is greater among participants who speak the language of the debate: that is, greater among French speakers than English speakers for the French debate, and greater among English speakers than French speakers for the English debate. This is very likely a function of the media markets in which the debates are advertised and promoted.

Second, debate awareness is relatively modest. This low anticipatory salience is reflected in the analysis of the Twitter conversation in Section 4.1.2. While variation in individuals' attention to politics naturally places a limit on aggregate public awareness of the debates, and awareness of the election more broadly, there may still be opportunity to drive up debate awareness—particularly in the English market—in future federal election campaigns.

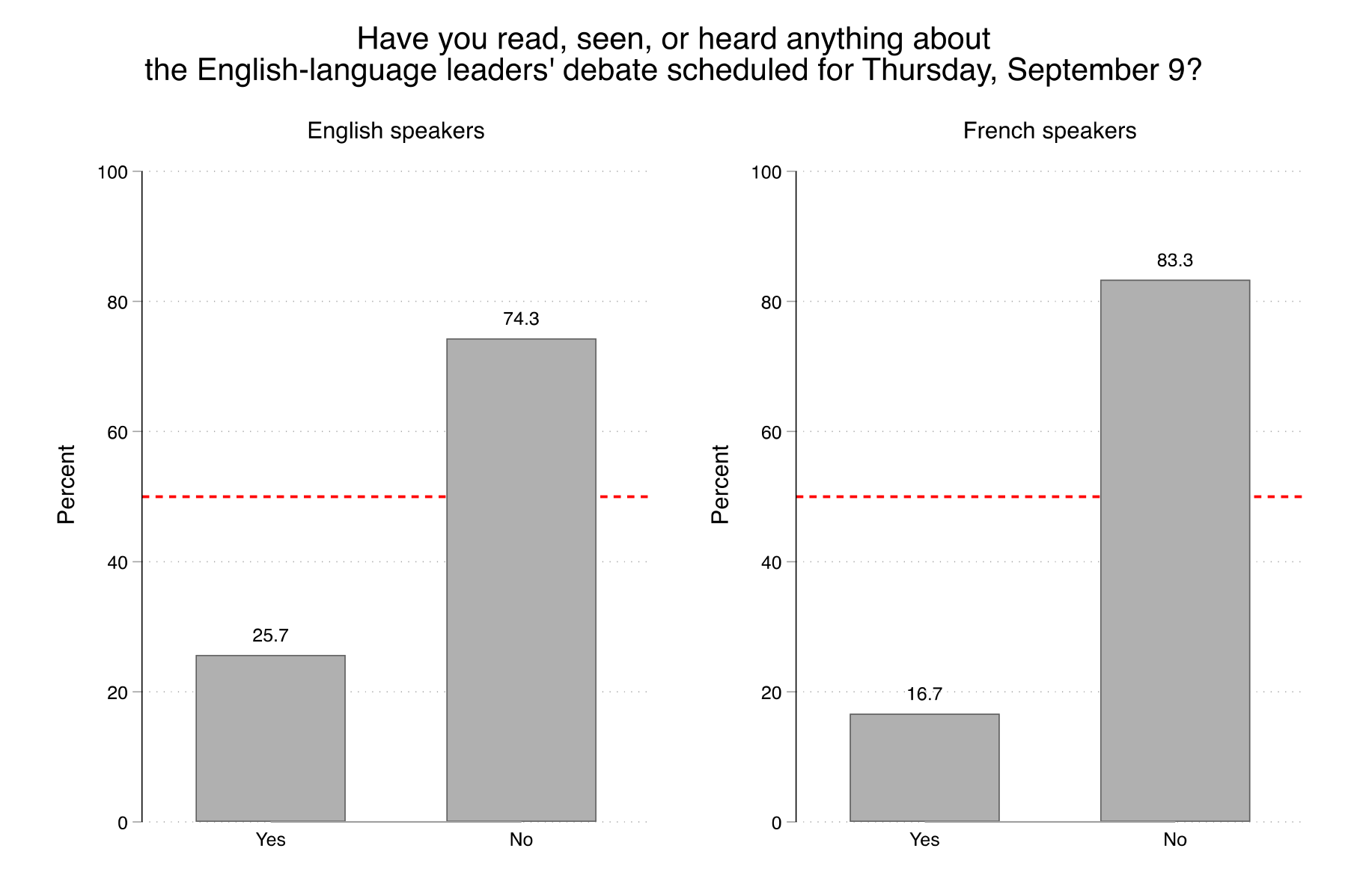

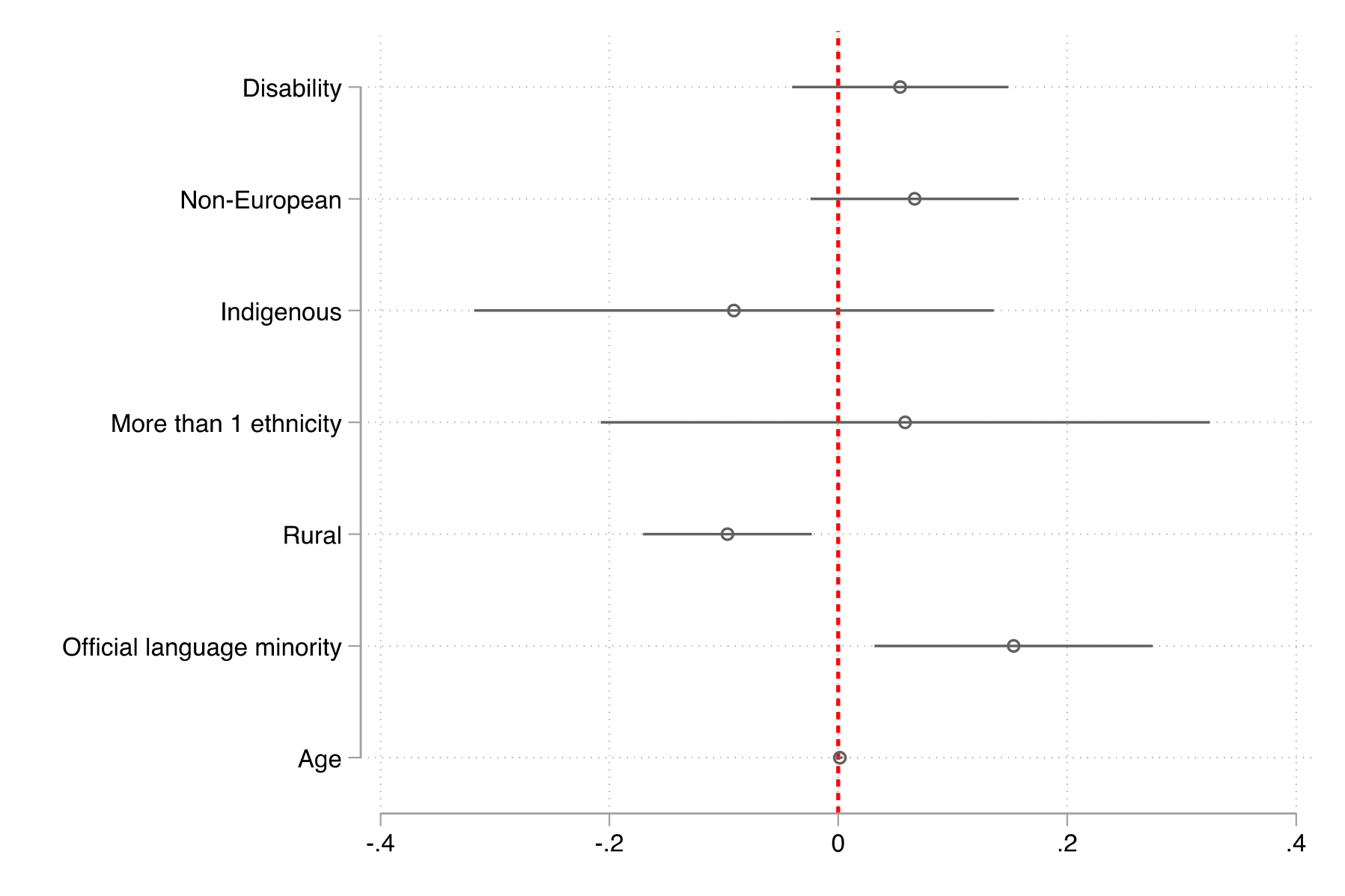

We also explored how awareness of the debates may have varied across particular demographic groups. To do this, we modeled a single binary indicator of debate awareness as a function of disability identity, ethnicity, rural/urban residence, official language minority status, and age. A plot of the OLS coefficients, and their associated 95% confidence intervals, are reported in Figure 3. We find that: (1) rural residents were roughly 6 percentage points less likely to be aware of the upcoming debates than urban residents; (2) official language minorities were roughly 10 percentage points more likely to be aware of the debates than those who are not official language minorities; and (3) each additional year of age is associated with a 0.3 percentage point increase in debate awareness. We did not find disability or ethnicity to be associated with differences in debate awareness at a conventional level of statistical significance.

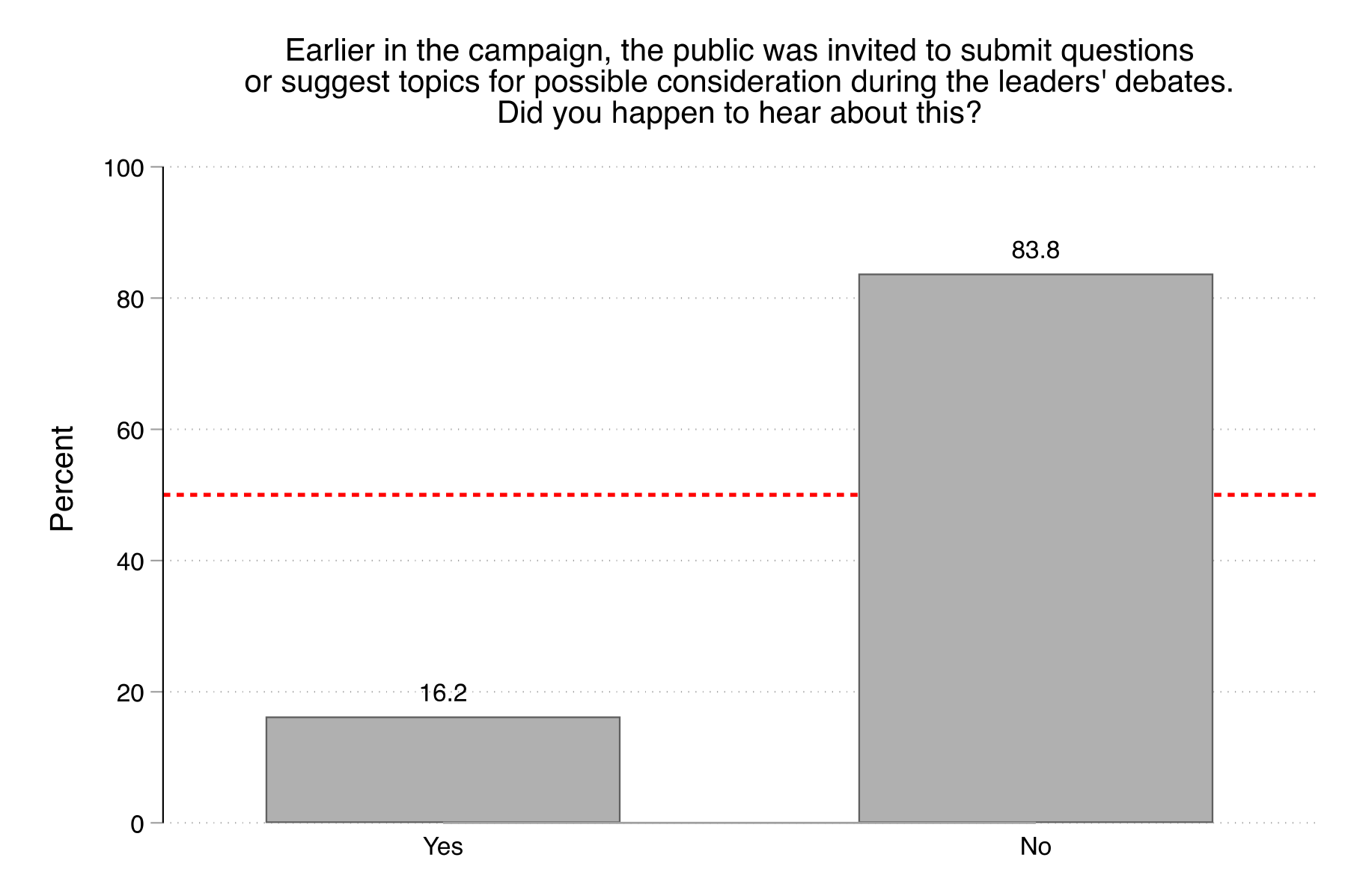

Prior to the debates, the public was invited to submit questions or topics for possible consideration during the debates. In the first wave of the survey, we asked participants whether they had heard about this opportunity. The results, reported in Figure 4, show that a very large majority had not. We find that only 16% of Canadians were aware that they could make these submissions. As with public awareness of the debates more broadly, there is an opportunity to expand the public's engagement in future election campaigns. Indeed, as we show in Section 4.7.3, there is significant public support for debates in which "regular citizens" put questions to the party leaders. Thus, expanded awareness about the question submission process may stimulate greater interest in the debates themselves.

4.1.2 Pre-debate mentions on Twitter

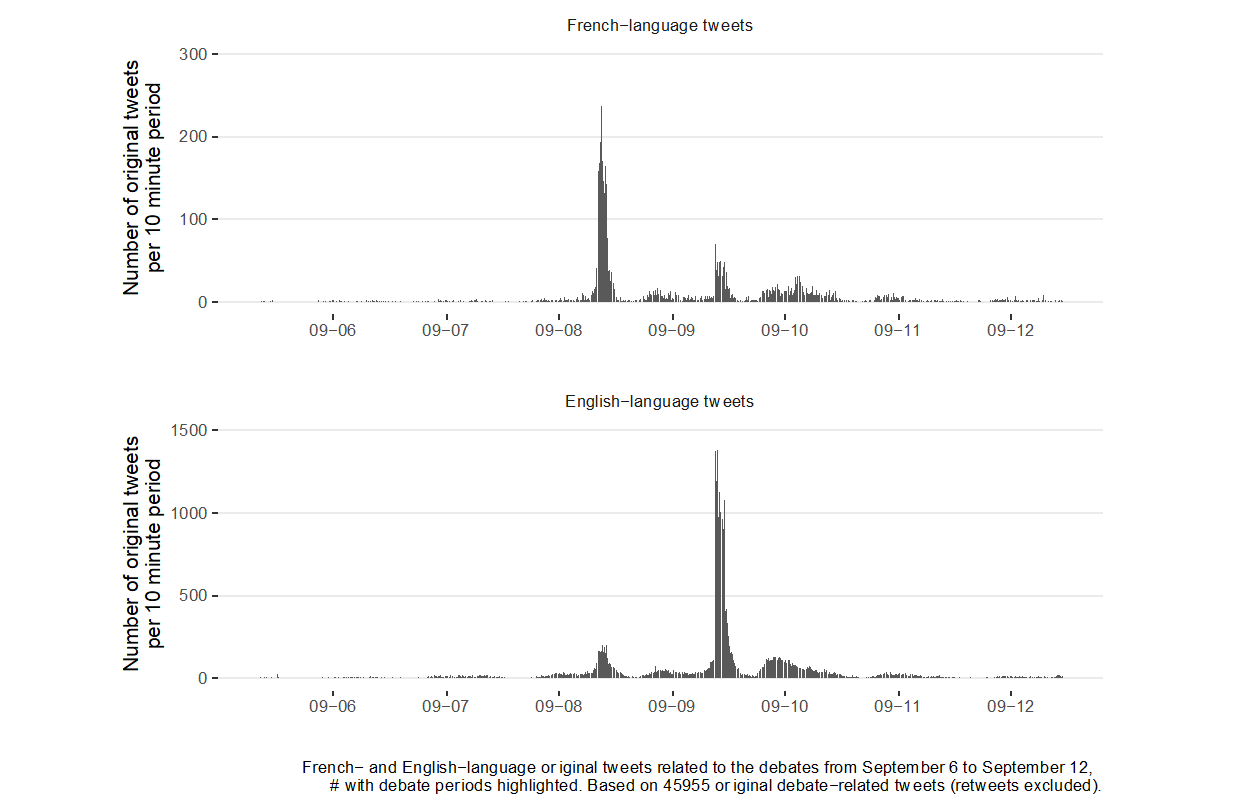

We also evaluated anticipation of the debates using Twitter data. Here we searched the Canadian politics tweet dataset for mentions of "debate," "débat," and moderator names. Figure 5 shows debate-related mentions from 3 days before the French-language leaders' debate to 3 days after the English-language leaders' debate. The top panel shows the volume of French-language tweets and the bottom panel shows the volume of English-language tweets. There was minimal anticipatory discussion on Twitter, with the bulk of the conversation happening during the debates themselves and during the day after the English-language debate.

4.2 Viewership of the debates

4.2.1 Overall viewership and across demographic groups

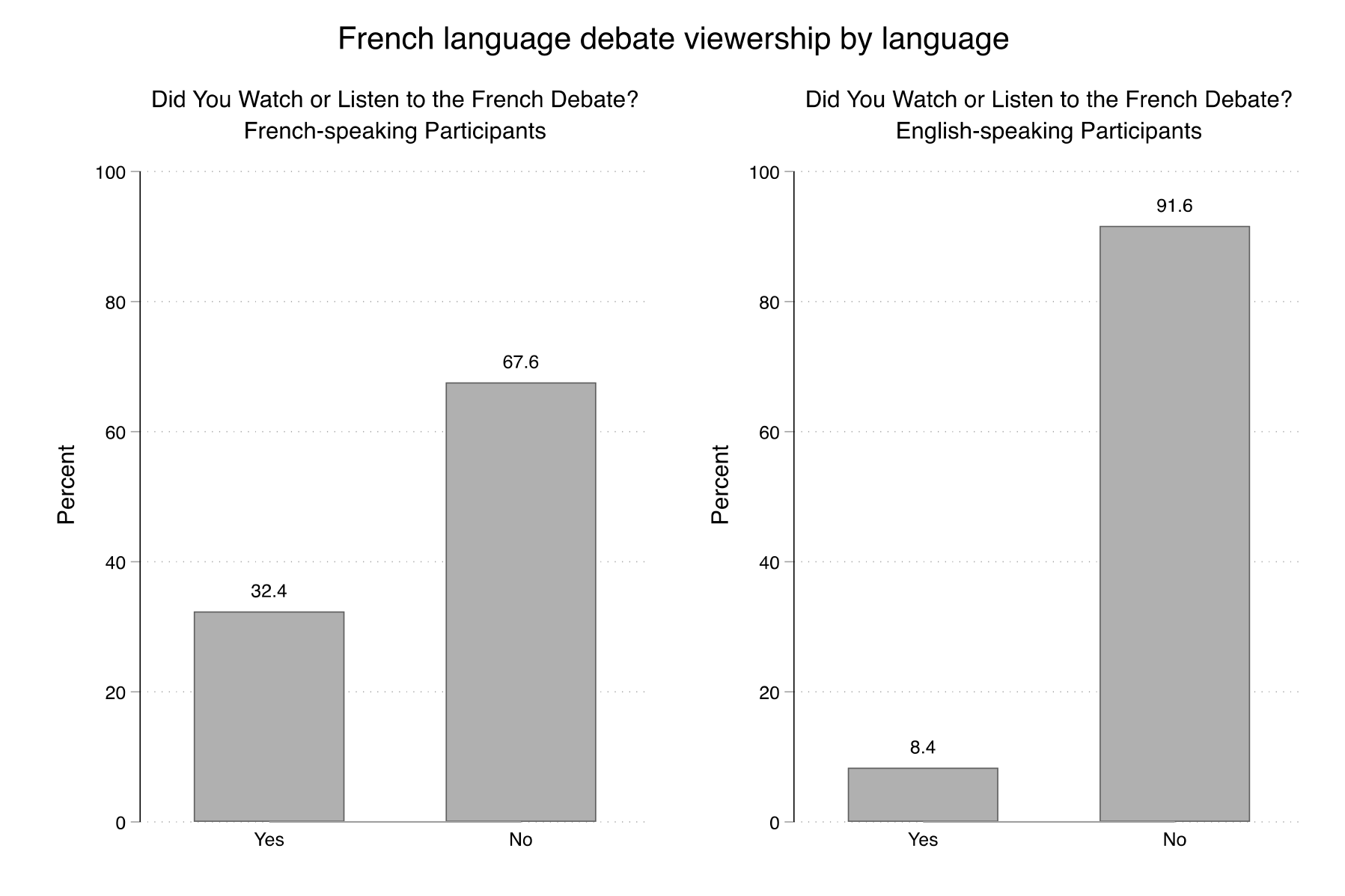

We analyzed viewership details using self-reports from the second wave of the survey. Figure 6 reports viewership of the French debate by participant language. We estimate that just under one-third of French-speakers (32%), mostly from Quebec, watched the September 8 French debate. Less than one in ten (8.4%) of English-speaking Canadians did the same.

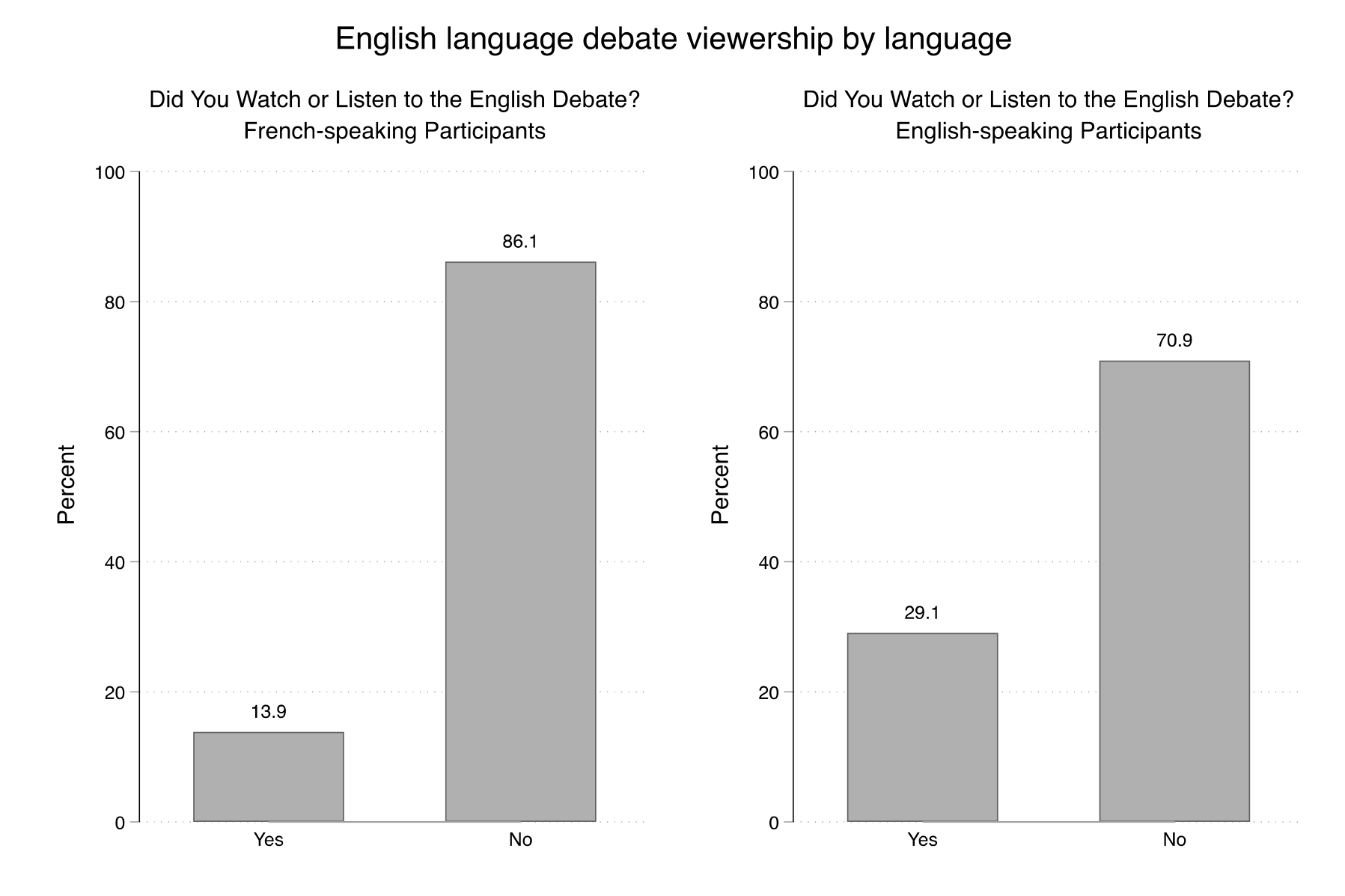

Figure 7 reports the viewership of the English debate—again disaggregated by participant language. We estimate that 29% of English-speakers watched the September 9 English debate—while 14% of French-speakers did the same.

As we did in our analysis of pre-debate awareness, we also examine how viewership of the debates varied across certain demographic groups. To do this, we modeled a binary indicator of debate viewership as a function of disability identity, ethnicity, rural/urban residence, official language minority status, and age. Figure 8 reports the OLS point estimates and their associated 95% confidence intervals. These results point to a pattern similar to that of pre-debate awareness. We find that: (1) rural residents were approximately 10 percentage points less likely than urban residents to watch a debate; and (2) official language minorities were 15 percentage points more likely to watch a debate than those who are not official language minorities. Disability identity, ethnicity/ancestry, and age did not have a statistically significant impact on debate watching at the p < .05 level.

4.2.2 Duration of viewership

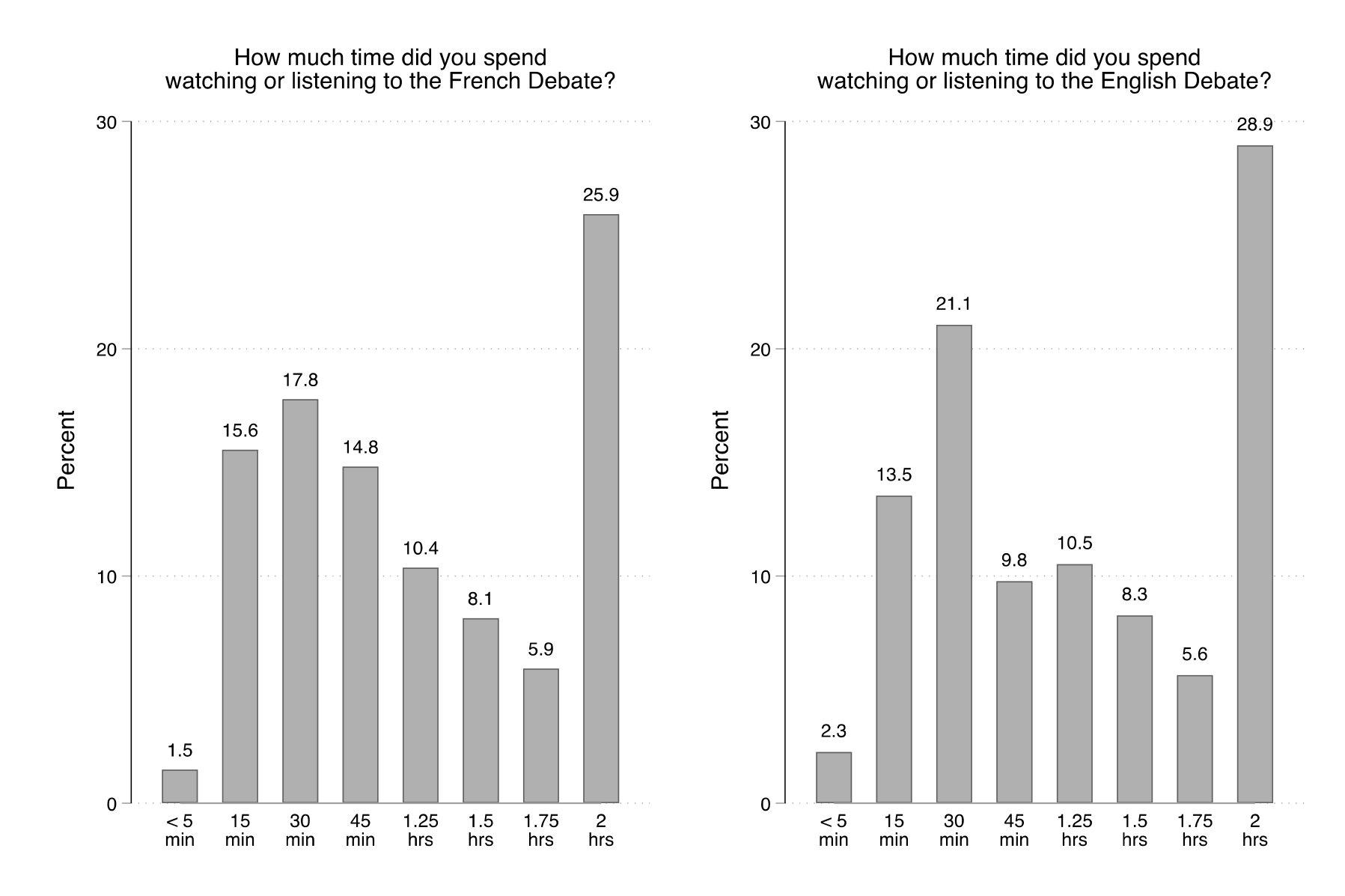

We deepened our understanding of viewership patterns by asking those who watched/listened to a debate: how much time did you spend watching or listening? The distribution of responses is reported in Figure 9. The pattern is similar for both debates: a majority of those who tuned in did so for a majority of the time. Roughly one quarter of the viewership of each debate tuned in for the entire two-hour debate. At the same time, roughly 35% of the French debate viewership—and 37% of the English debate viewership—watched/listened for 30 minutes or less.

We believe that these findings—particularly the fact that only about a quarter of the viewership watched/listened to the full two-hour debate—is an important point of reflection for understanding how Canadians choose to consume modern leaders' debates. It also provides some additional context when interpreting the impacts of debate viewership set out in Section 4.6.

4.2.3 Viewership medium

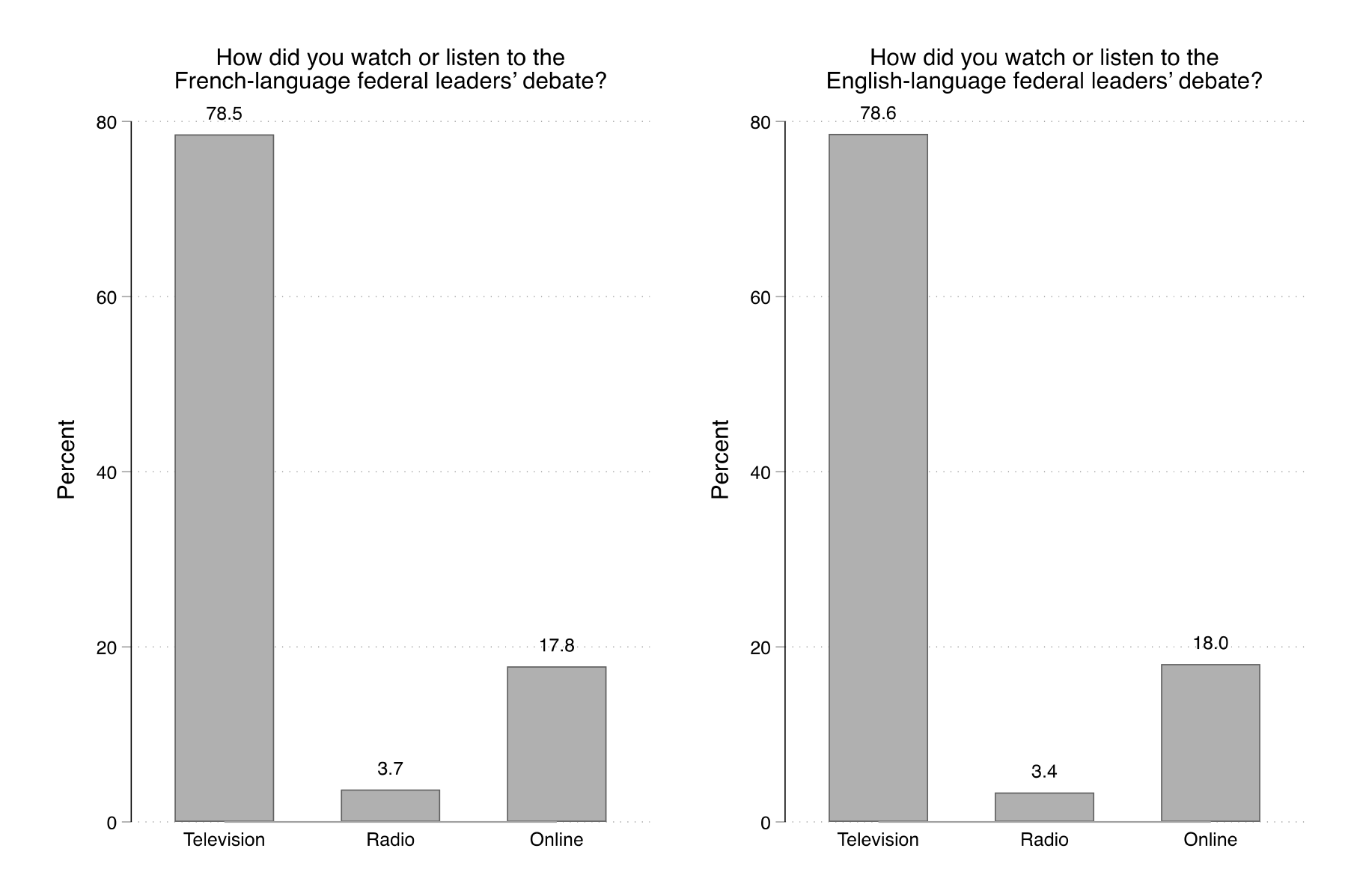

Debate viewers were also asked how they watched the debates: i.e., on television, on the radio, or online. The results are reported, for both debates, in Figure 10. The findings are virtually identical for the French and English debates: the vast majority of viewers—nearly four in five—watched on television. Just under one in five watched online and only 3-4% listened on the radio. In short, television remains the dominant medium of debate consumption.

4.3 Reasons for not watching the debates

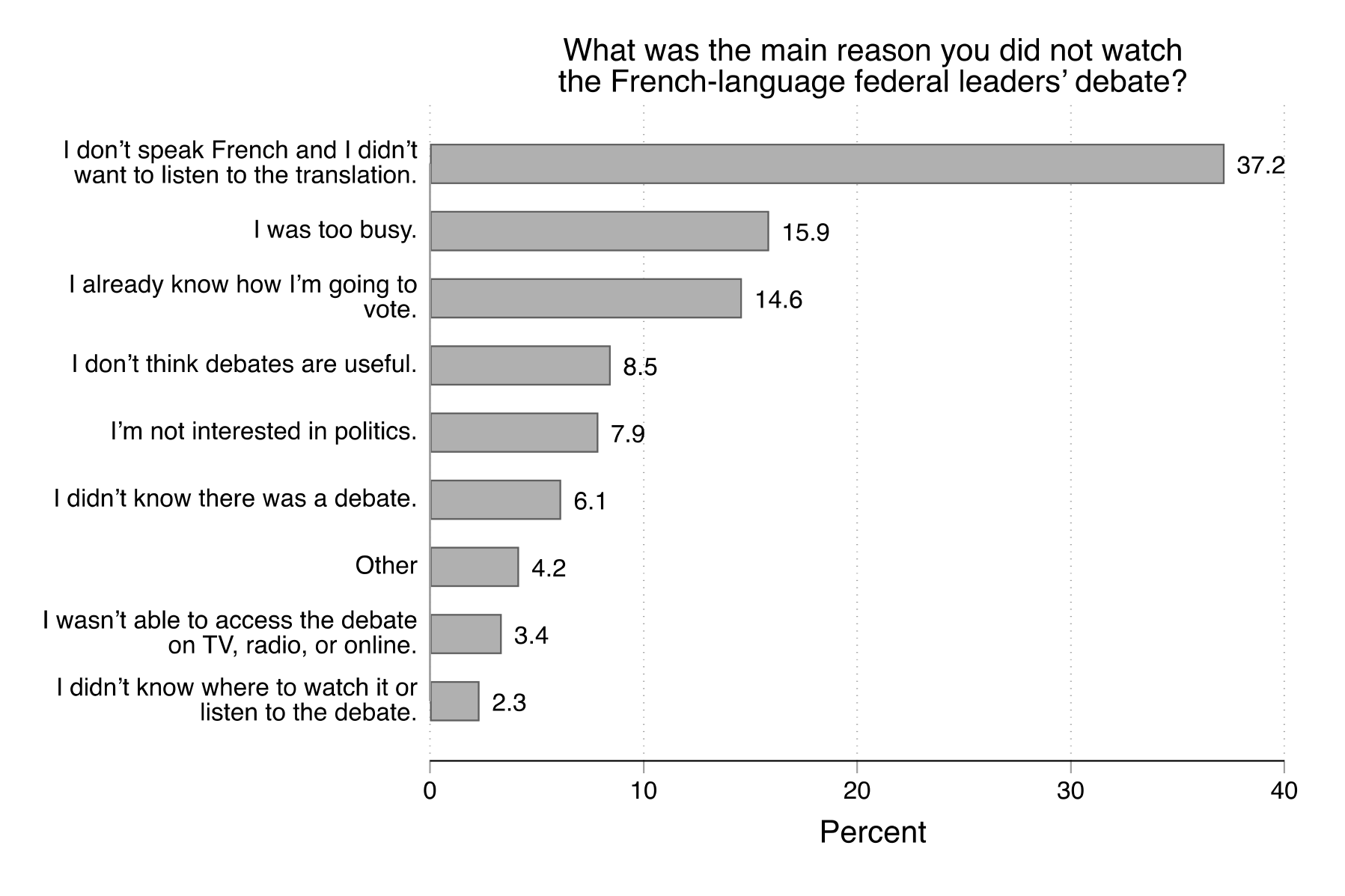

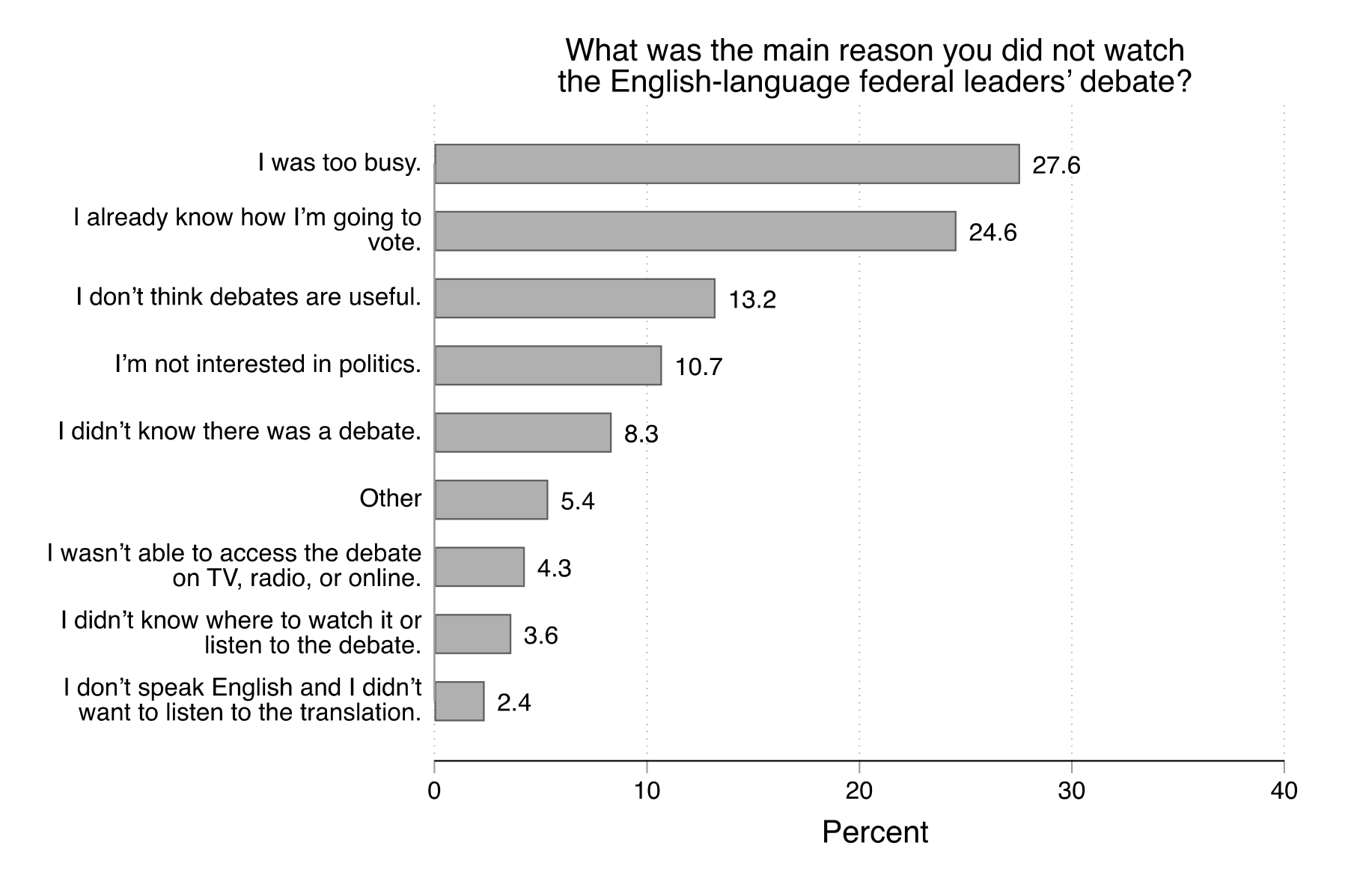

For those who indicated they did not watch a debate, we probed further—asking what was the main reason they did not watch. Figure 11 reports the answers for non-watchers of the French debate and Figure 12 reports the same for non-watchers of the English debate.

The most common answer for not watching the French debate was that the participant did not speak French and didn't want to listen to the translation—perhaps not surprising given that this question was put to everyone who did not watch the French debate, French- and English- speakers alike. The second most common response was "I was too busy" (16%). Another common set of responses all pertain to a perceive lack of use for the debate or a lack of interest in politics more broadly: "I already know how I'm going to vote (15%); "I don't think debates are useful" (8%); and "I'm not interested in politics" (8%). A further, smaller subset of responses reflected a lack of awareness of or access to the debates: "I didn't know there was a debate" (6%); "I wasn't able to access the debate" (3%) and "I didn't know where to watch or listen to the debate" (2%).

With the exception of the language-based reason, the responses for non-watchers of the English debate largely mirror the responses for non-watchers of the French debate. The most common response (28%) was "I was too busy." The next most common set of responses again underscored a perceive lack of value or interest in the debate and in politics: "I already know how I'm going to vote" (25%); "I don't think debates are useful" (13%); and "I'm not interested in politics" (10.7%). Only a small proportion of non-watchers of the English debate attributed not watching to a lack of awareness or access: "I didn't know there was a debate" (8%); "I wasn't able to access the debate" (4%) and "I didn't know where to watch or listen to the debate" (4%).

These results are encouraging in that the reasons for not watching a debate do not typically come down to a technical problem with access: only 5-10% of non-watchers said they didn't watch because they didn't have access to the debate or didn't know how to access the debate. By contrast, a significant proportion attribute not watching to a lack of interest. While there is likely opportunity to convince some of these Canadians of the value of the debates, future viewership will naturally be constrained by individuals' interest in politics. The response of being "too busy" to watch is more difficult to interpret. For some it could again reflect a lack of interest in the debate, but for others it may reflect irresolvable scheduling conflicts such as work or childcare. This suggests further reflection in terms of when to schedule a debate given Canadian time zones—as well as whether more can be done to promote access to clips of the debates after the fact. (In Section 4.7.6, we take up the question of when Canadians would like to watch a debate live.)

4.4 Engagement with the debates

4.4.1 Engagement on Twitter

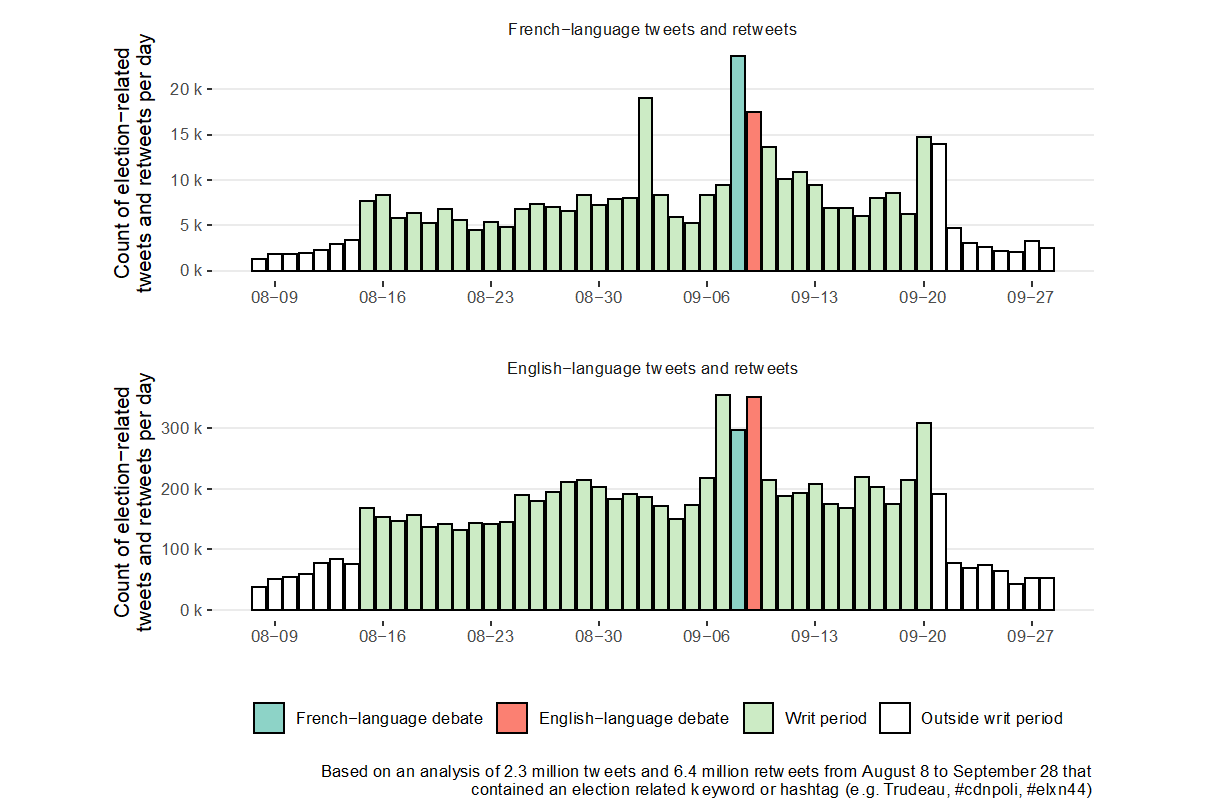

The leaders' debates were important junctures during the election on Twitter. Figure 13 shows the volume of Canadian-politics related tweets from August 8 to September 28, 2021, with the top panel showing French-language tweets and the bottom panel showing English-language ones. September 8 and 9, when the leaders' debates were held, were among the most concentrated period of discussion of Canadian politics in both languages. The day of the French debate witnessed, by a large margin, the most French-language politics-related Twitter activity of the campaign—substantially outstripping Election Day itself. The day of the English debate had the second highest English-language politics-related Twitter activity of the campaign, again higher than on Election Day.

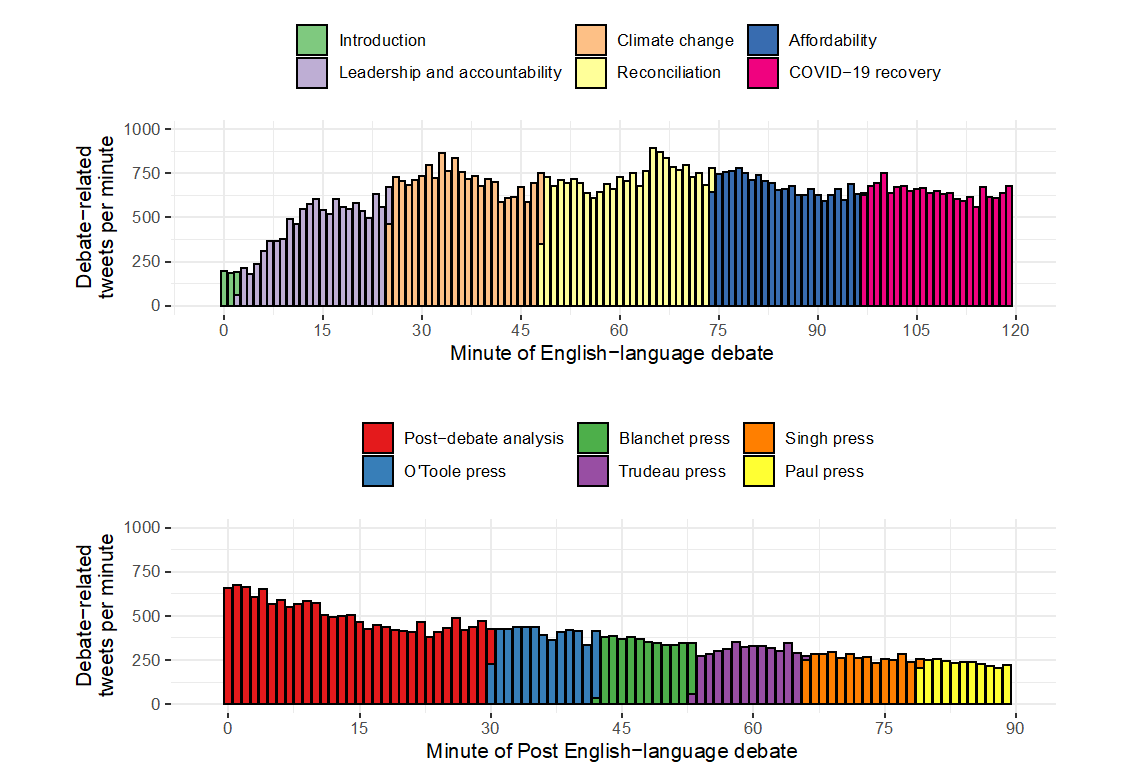

In addition, we identified debate-related tweets based on keywords, again using "debate," "débat," moderator names, and party leader names. A total of 107,889 debate-related tweets and retweets were posted in the four hours of the two debates: 31,090 during the French-language debate and 76,799 during the English-language debate.

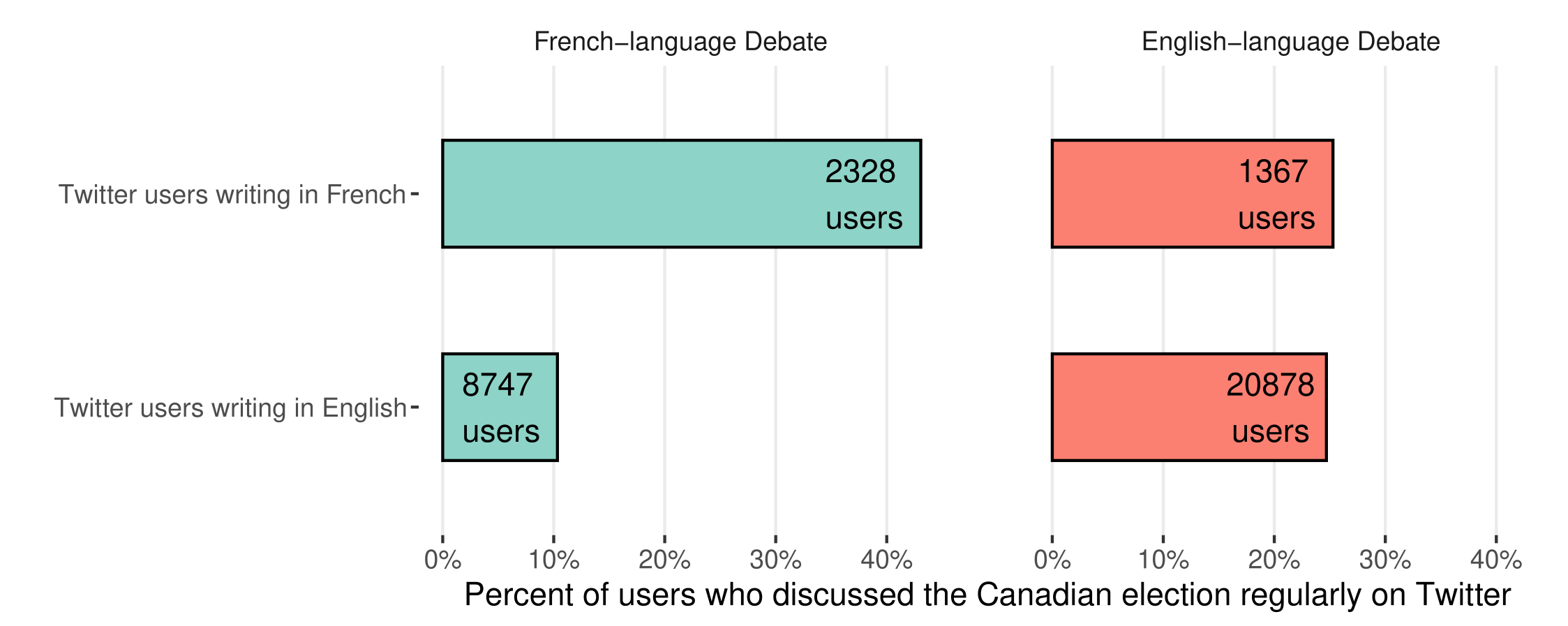

Throughout the election, we identified 84,560 accounts that habitually post about politics and evaluated the extent to which this politically active group also shared their opinions during the leaders' debates. Figure 14 shows the number and percentage of users who habitually comment on Canadian politics who live-tweeted the debates.

Over 40% of the habitually posting French-language users posted in the two-hour window of the French-language debate, while only about 11% of English-users did so. Just over 25% of both French- and English-language users live tweeted about the English-language debate. The topics and content of these tweets was varied and included cheering on particular party leaders, discussing the debate format and content, and commenting on specific policy areas.

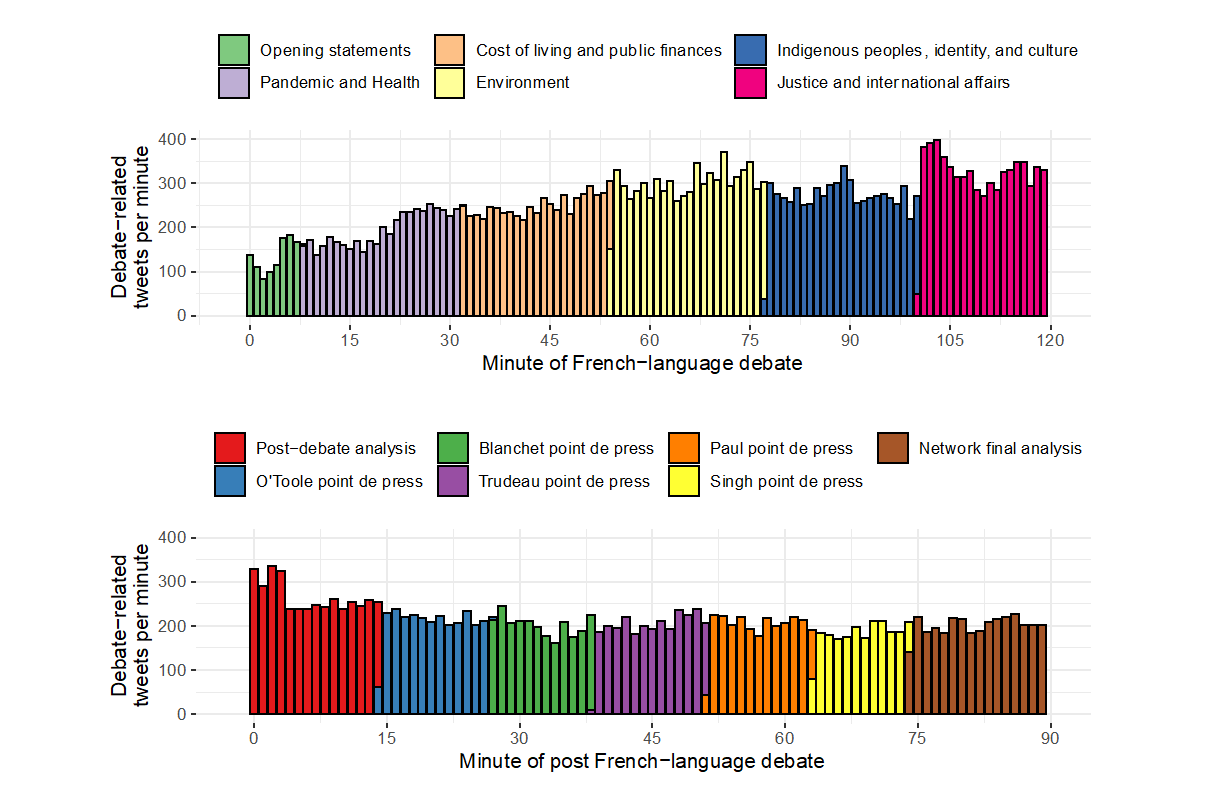

Looking deeper into the debate-related conversation during the two debates on Twitter, we can examine the volume of tweets during and immediately after each debate. Figures 15 and 16 show these results. The debates are divided into their thematic areas based on the time of the tweet—with the bottom plot showing the post-debate analysis and post-debate media scrums with the leaders. The volume of conversation on Twitter increased throughout both the English- and French-language debates. Caution, however, should be taken in attributing changes in tweet volume to changes in debate topic.

Figure 16 shows the same volumes for the English-language debate and immediate post-debate period. Volume was more steady throughout the debate, but fell off after the debate. Starting the English-language debate at 9 pm Eastern—an hour later than the French-language debate—may have contributed to this drop of interest, with the number of debate-related tweets falling to approximately 250 per minute during the last press conferences of the evening.

4.4.2 Discussion of debates with others

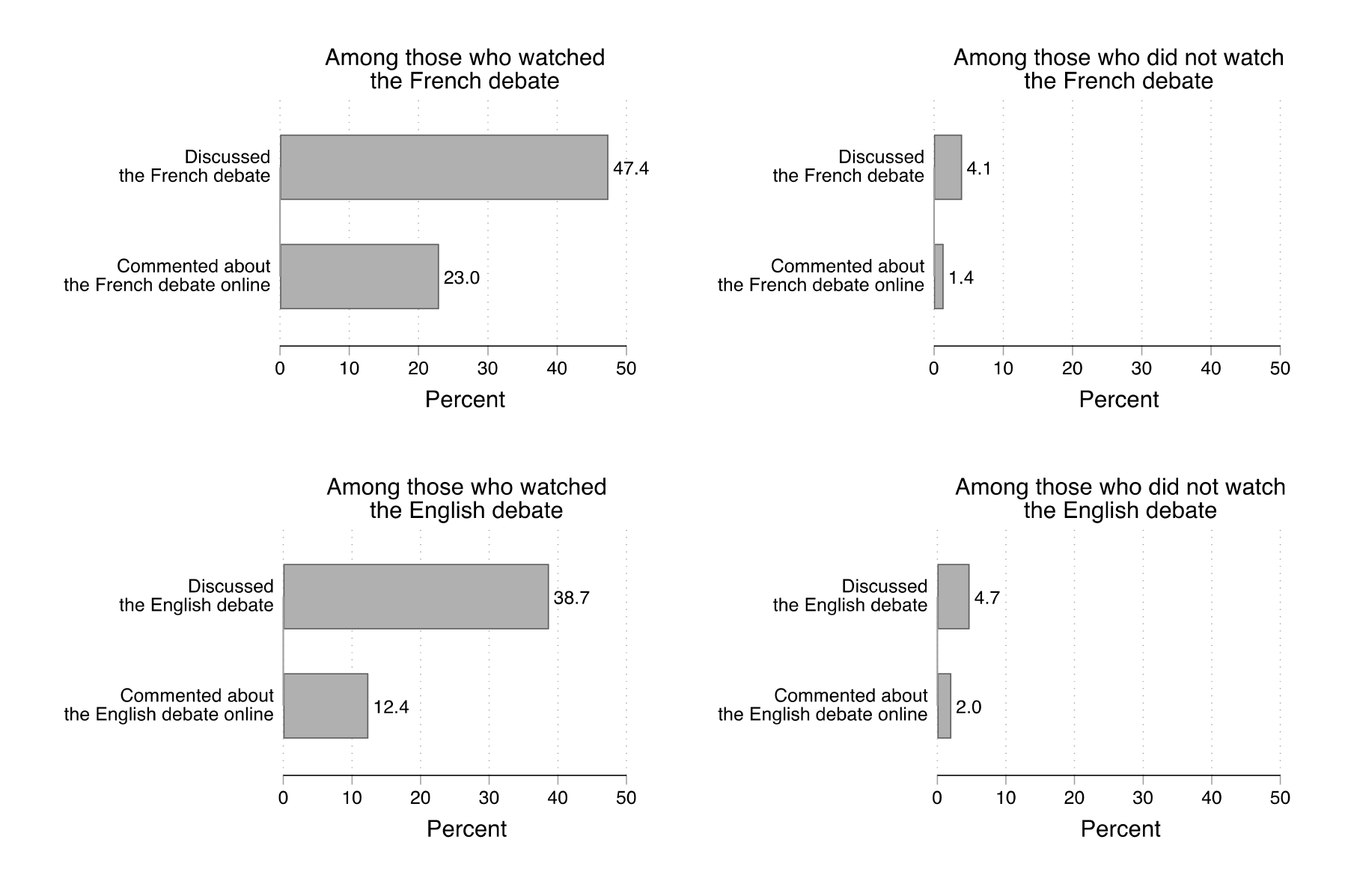

In the second wave of the survey, all participants—regardless of whether they had watched a debate—were asked whether they had discussed what happened in each debate with others. Participants were also asked, again for each debate, whether they commented on social media about what happened in the debate. The results are presented in Figure 17, disaggregated by debate viewership. These results highlight a healthy degree of engagement with the debates after the fact: nearly half (47%) of French debate viewers discussed what happened with others and nearly two in five (39%) of English debate viewers did the same. Online engagement was more modest but still encouraging: 23% of French debate viewers and 12% of English debate viewers commented about the respective debate online. Engagement among nonviewers (right column) is much more limited: less than 5% of non-viewers discussed the debates or commented about them online.

4.5 Evaluations of the debates

4.5.1 Survey-based evaluations

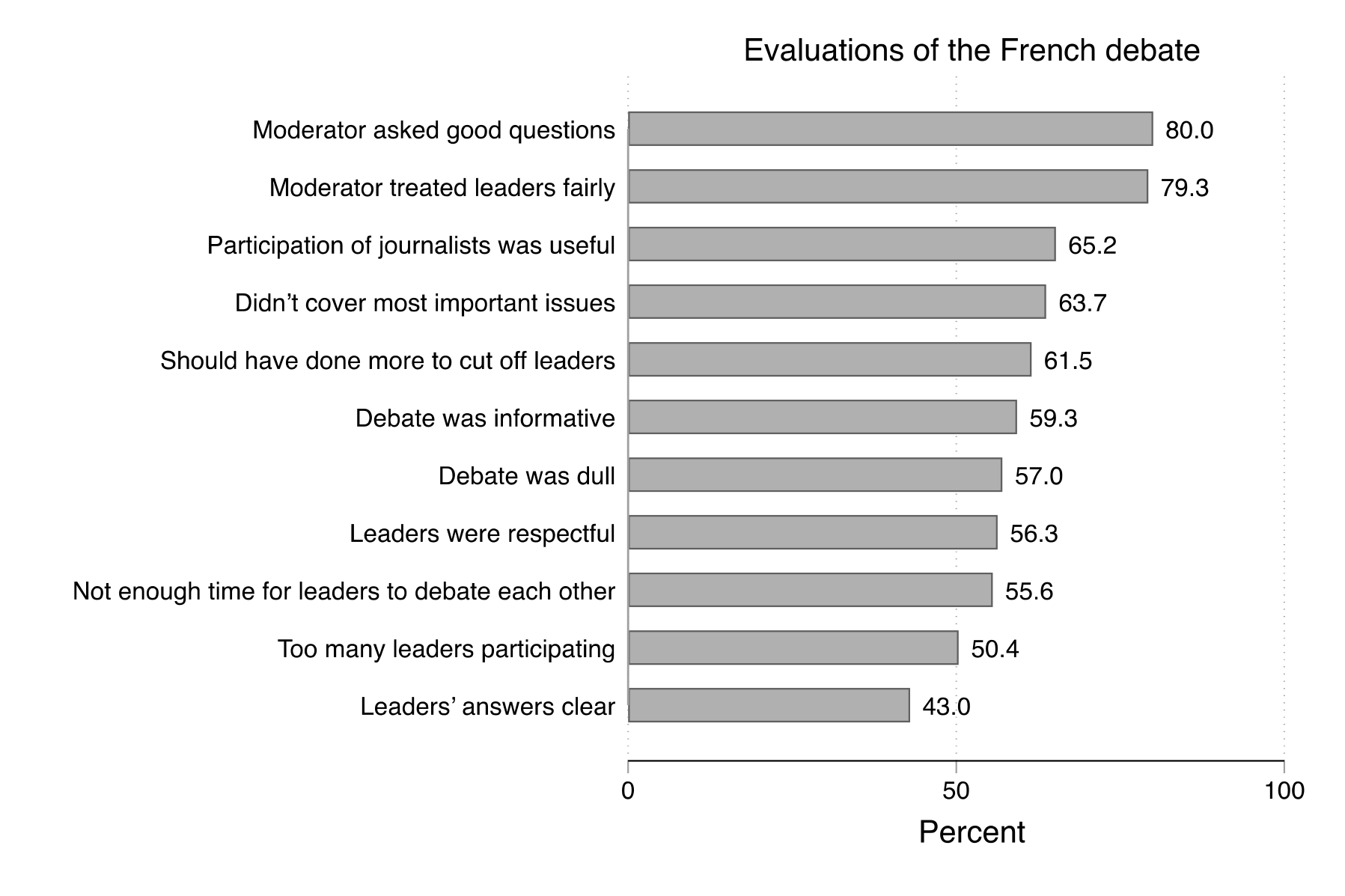

When participants in the second wave reported watching a Commission-organized debate, we followed up with a series of questions meant to elicit their opinions about a wide range of aspects of the debate. Participants were asked to indicate whether they strongly disagreed, somewhat disagreed, somewhat agreed, or strongly agreed with a set of 11 statements about the debate. Figure 18 reports the results for French debate viewers in the form of the percent in agreement with each statement (i.e., combining those who somewhat or strongly agreed).

French debate viewers gave generally high marks to the moderator. Large majorities felt that he asked good questions (80%) and treated the leaders fairly (79%). Furthermore, nearly 2 in 3 (65%) French debate viewers thought that the participation of the additional journalists was useful. The chief reservation with respect to the moderation was in terms of managing the leaders' speaking time: 62% said that the moderator "should have done more to cut off leaders when it was warranted" and 56% felt there wasn't enough time for the leaders to "debate each other directly." Managing leaders' speaking time is a thorny issue, one to which we return in Section 4.7. We also note here the recurring frustration that focus group participants experienced when trying to follow exchanges in which leaders talked over each other.

With regards to general judgments of the debate and its format, roughly 3 in 5 (59%) French debate viewers found the debate informative. At the same time, a slightly smaller fraction (57%) characterized the debate as "dull". Fully 64% reported that the debate "didn't cover the issues that were most important" to them. French debate viewers were more evenly split (50%) on another crucial format question—namely whether there were "too many leaders participating in the debate." (We unpack in detail Canadians' preferences with respect to leader participation in Section 4.7).

Lastly, French debate viewers gave the party leaders a mixed scorecard. A majority (56%) found the leaders to be "respectful of each other." Less than half of viewers (43%) felt that leaders' answers were "clear." This maps onto a common concern of focus group participants who, upon viewing clips of the debate, found that leaders' answers lacked detail.

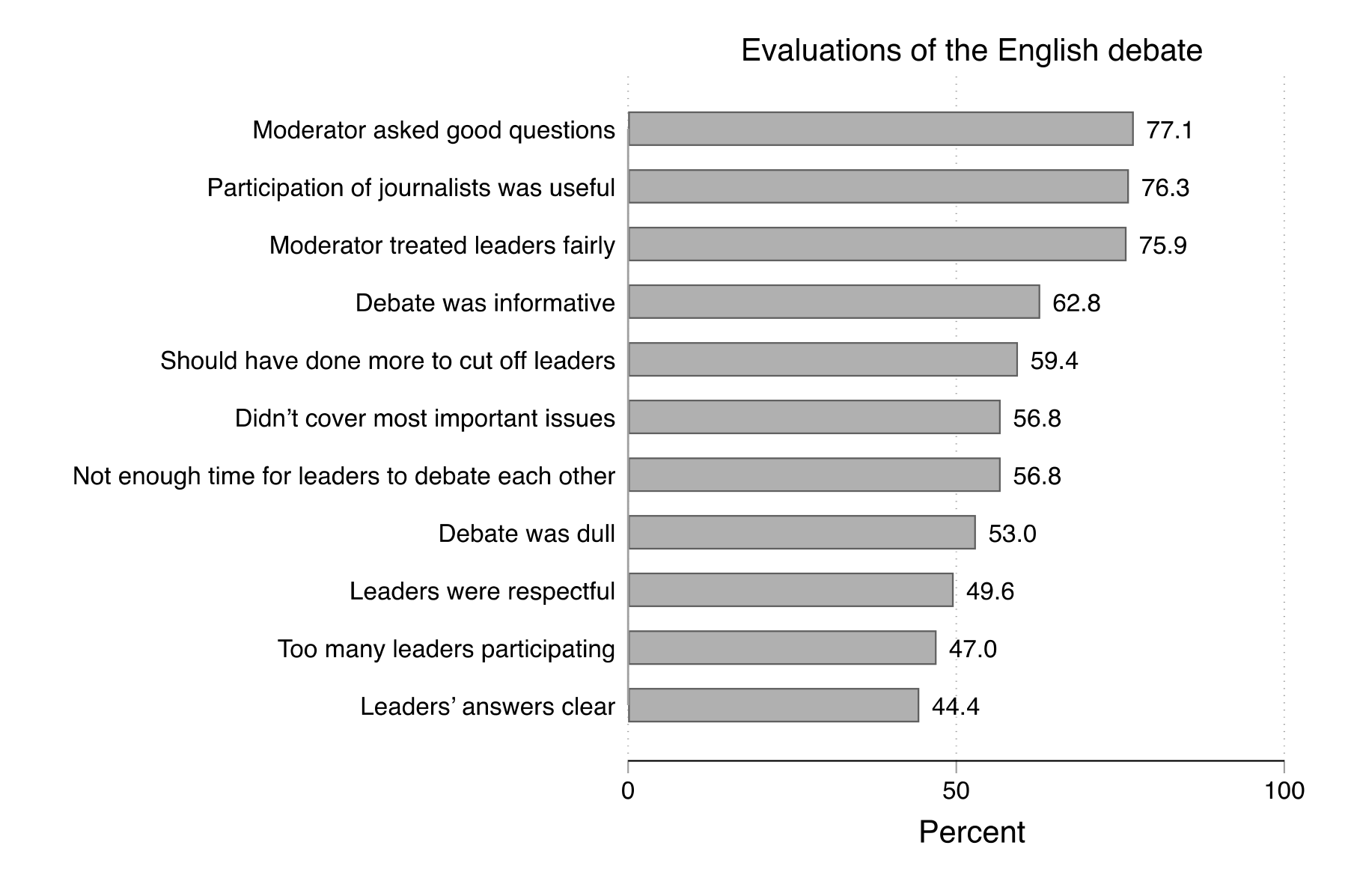

Figure 19 reports the results for English debate viewers. The judgments of English debate viewers mirror those of French debate viewers. Again, top marks are reserved for the moderator and participating journalists. Large majorities believed that the moderator asked good questions (77%) and treated leaders fairly (76%). In addition, over three quarters (76%) of viewers found the participation of the additional journalists useful. Similar to the French debate, however, roughly 3 in 5 viewers (59%) thought that the moderator should have done more to "cut off" leaders—while a majority (57%) felt that the moderator "didn't give the leaders enough time to debate each other directly."

On the debate and its format, 63% of English debate viewers agreed that the debate was "informative." A smaller number (53%) also characterized the debate as "dull." As with the French debate, a majority of viewers (57%) still felt that the debate "didn't cover the issues that were most important" to them. Viewers were split on the question of leader participation—with 47% agreeing with the statement that there were "too many leaders participating in the debate."

The party leaders were also given lukewarm reviews by English debate viewers. Half (50%) characterized their conduct during the debate as "respectful" and under half (44%) characterized their answers as "clear."

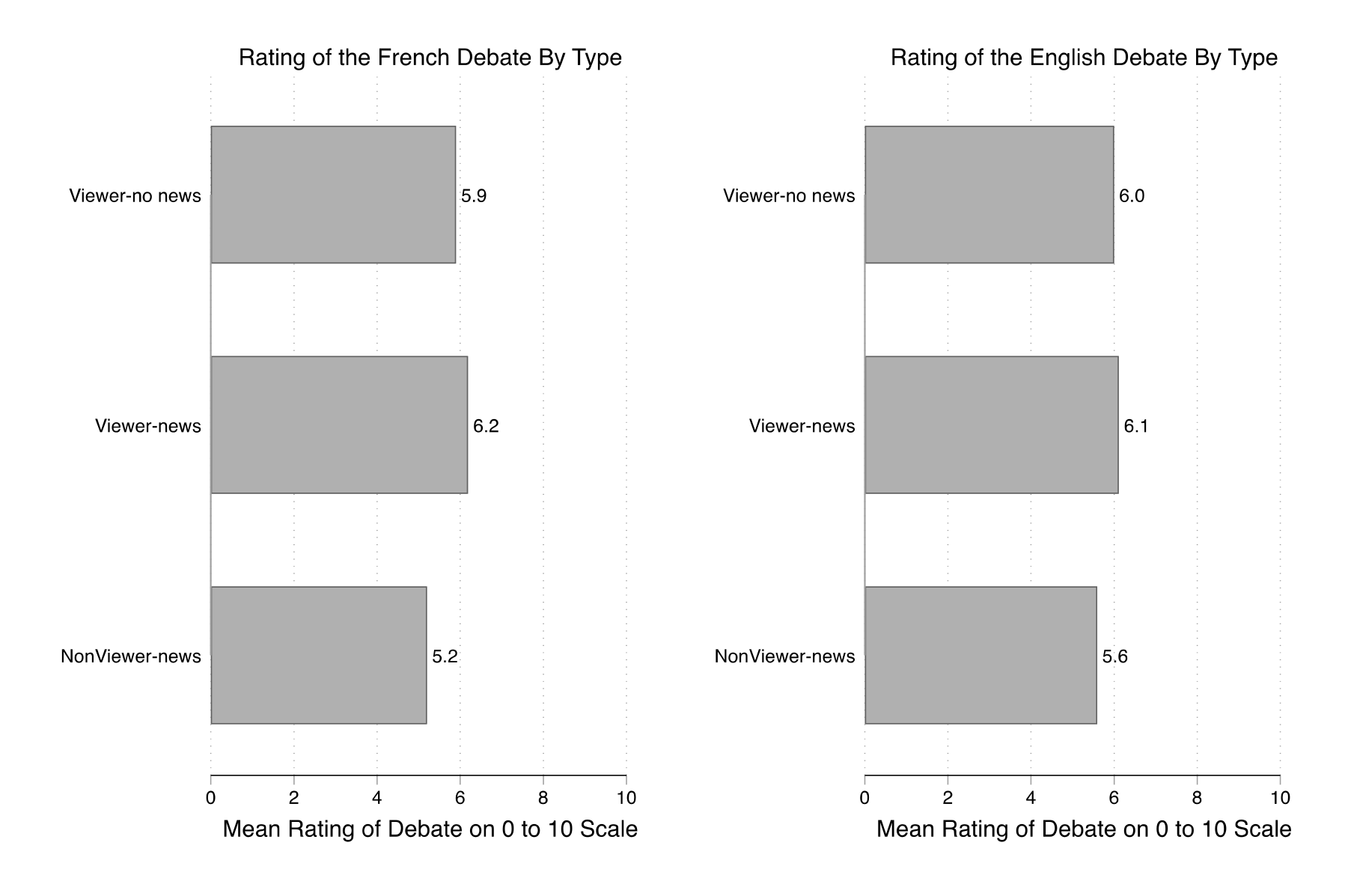

To supplement these assessments of specific aspects of the debate, we also asked participants to rate the debates more generally on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 meant "a very bad debate" and 10 meant "a very good debate." We put this question not only to participants who watched the debate but also to those who did not—provided that they had read, seen, or heard at least some news or commentary about what happened in the debate. Figure 20 reports, for each debate, the average debate rating (on the 0 to 10 scale) for three different types of survey participants: (1) those who watched the debate but did not consume news or commentary about it; (2) those who watched the debate and consumed at least some news or commentary about it; and (3) those who did not watch the debate but did consume at least some news or commentary about it.

Viewers of each debate typically gave the debate a moderately positive rating—with the average rating hovering near 6 on the 0 to 10 scale. Participants who did not see the debate but did consume news or commentary had a somewhat less favourable assessment. Indeed, in the case of both the French and English debates, debate viewers who consumed news had a statistically significantly more positive assessment than non-viewers who consumed news (debate viewers who consumed no news about the debate constituted only a small fraction of the sample and thus their average rating should be interpreted with caution). While this finding is only suggestive, the difference in assessments between viewers and nonviewers implies that the act of actually watching a debate—rather than merely consuming news or commentary about it after the fact—may be associated with more favourable views of the debate.

4.5.2 Twitter-based evaluations

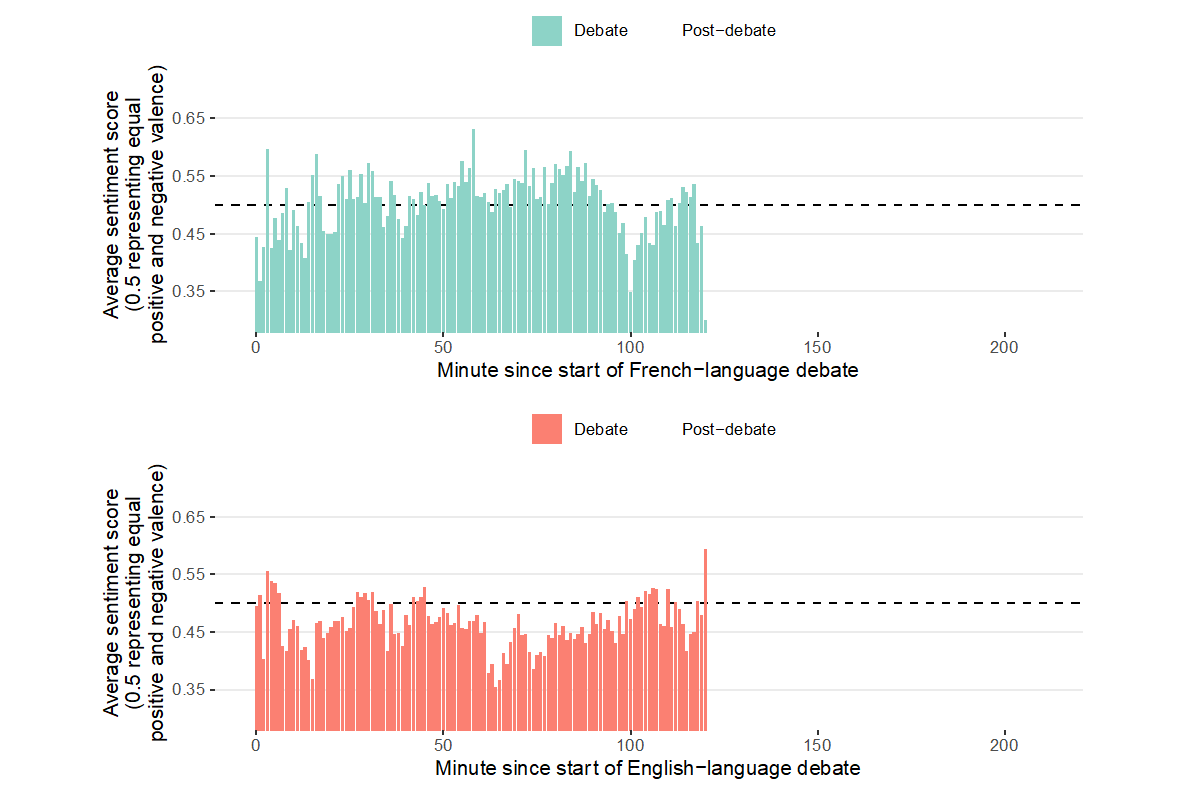

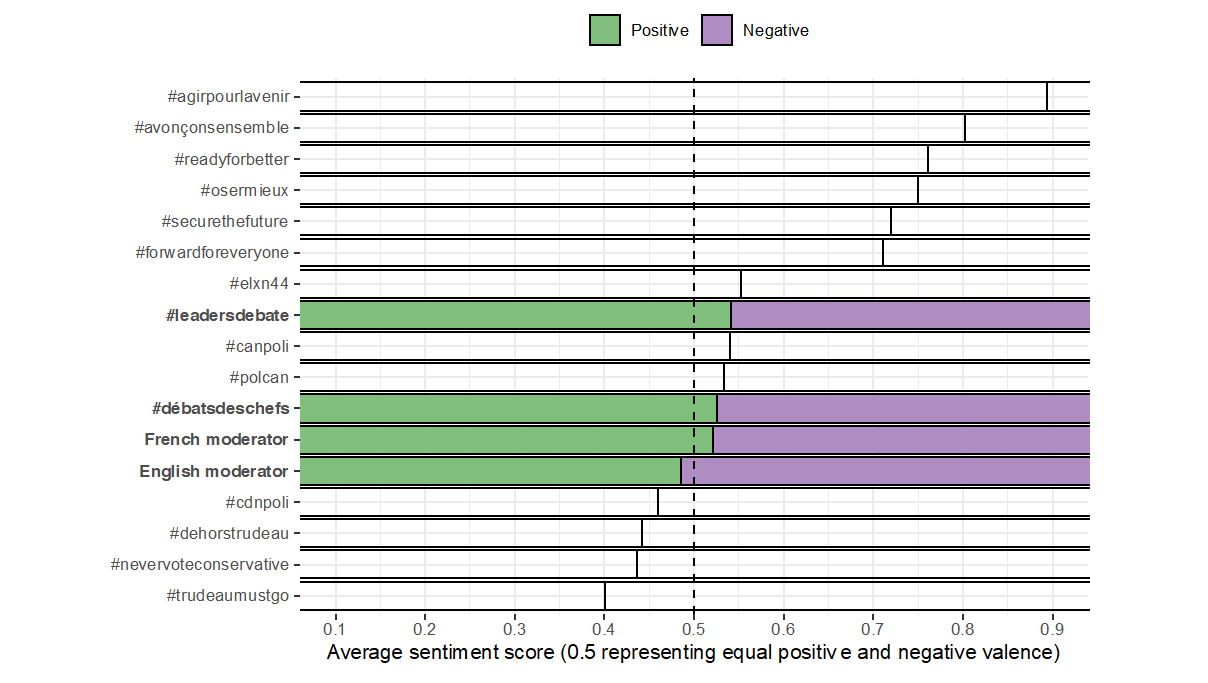

Next, we turn to a sentiment-based analysis of the Twitter conversation during and in the immediate aftermath of the debates. Figure 21 shows the overall sentiment of tweets related to both the French-language debate (top panel) and English-language debate (bottom panel). Sentiment related to both remained close to the neutral position (0.5), with the most noticeable trend being a more negative sentiment in the tweets in the post-French language debate.

We use a similar sentiment methodology to examine specific themes of discussion. Figure 22 shows overall sentiment for a variety of election-related hashtags, as well as for mentions of the debate moderators. The sentiment dictionary employed here correctly identifies positive and negative hashtags, with anti-Trudeau and anti-Conservative Party hashtags having overall negative sentiment and pro-Liberal, pro-Conservative, and pro-NDP hashtags having overall positive sentiment. The debate-related themes are those with the darkest bars and they fall between the pro- and anti-hashtags, with overall sentiment at approximately 0.5—a neutral position. Tweets mentioning the moderator of the French-language debate were somewhat more positive than the moderator of the English-language debate, although the English-language debate hashtag was slightly more positive than the French-language one.

4.6 The impact of watching the debates

In this section, we explore the impact of watching the debates on a wide variety of political outcomes—from engagement to knowledge to behaviour. We did this by recontacting a portion of participants from the Wave 1 pre-debate survey and administering the same set of questions in the Wave 2 post-debate survey. In this way, we can compute the within-individual differences, if any, in these outcomes. Moreover, by comparing these within-individual differences between those who did—and did not—watch a debate, we gain important leverage on the question of how watching the debates impacted these various outcomes. Details on the methodology used to estimate debate impacts can be found in Section 3.1.1.

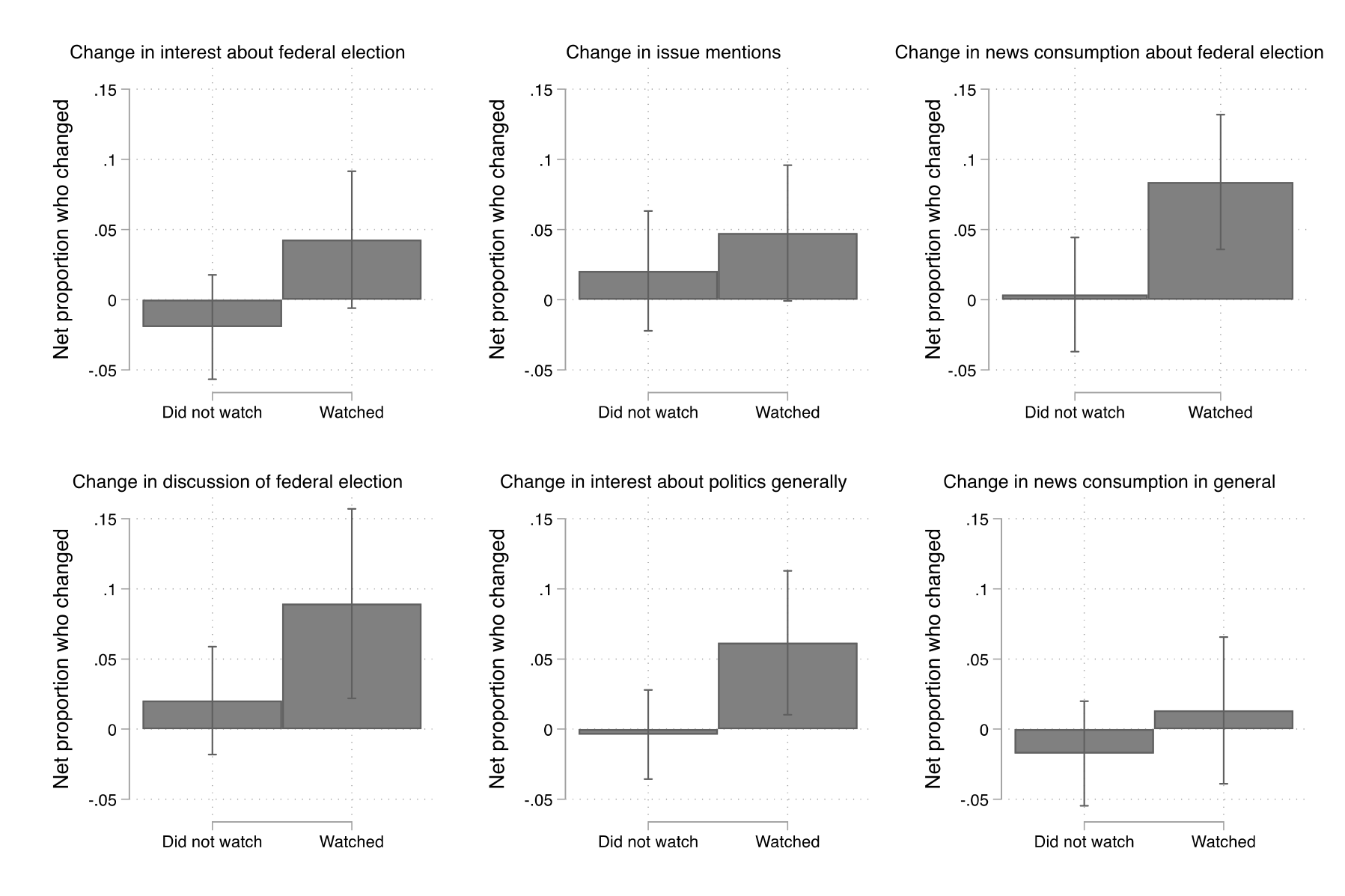

4.6.1 On political engagement

We begin by exploring the impact of debate watching on six outcomes designed to capture engagement with the election and with politics more generally. Figure 23 reports, for each of the six outcomes, the model predictions for those who watched at least one Commission-organized debate and for those who did not watch any Commission-organized debates—along with the 95% confidence intervals associated with each model prediction.

We make three findings. First, watching a debate was associated with an increase in interest in the federal election. Compared to individuals who did not watch, those who watched a debate had a 6 percentage point greater net increase in self-reported election interest. Second, debate watching was associated with an increase in the consumption of news about the federal election. Those who watched a debate had an 8 percentage point greater net increase in self-reported election news consumption than those who did not watch. Third, debate watching sparked greater interest in politics more generally. Compared to non-watchers, the debate watchers experienced a 6 percentage point net increase in self-reported general political interest. Furthermore, debate watching appears to have also contributed to greater discussion of the federal election—although the difference between watchers and non-watchers only approaches the conventional level of statistical significance (p = .08).

We did not find statistically significant evidence that debate watching was associated with more frequent "issue mentions" (i.e., listing more issues of interest in the election) or a greater volume of news consumption generally. On balance, these findings suggest that the debates did succeed in stimulating greater political engagement among those who watched them.

4.6.2 On political knowledge

Next, we turn to the question of whether watching a debate led to greater political knowledge. In Figure 24, we examine this from three prospectives. First, we investigated knowledge of party promises. Participants were given a set of 10 campaign promises (two for each of the parties participating in the Commission-organized debates) and were asked to identify which party, if any, made the promise. Second, we explored knowledge of current economic and social conditions with a series of four factual questions about the federal deficit, the unemployment rate, greenhouse gas emissions, and home prices. Third, we investigated participants' self-reported confidence that they knew "enough to make a good voting decision" in the election.

We find no evidence that the debate had an impact on these three knowledge outcomes. While watching a debate, for example, is associated with a net increase in knowledge of current conditions, the difference between watchers and non-watchers is not statistically significant. One possible explanation for the absence of debate impacts here is that the debates did not elicit the kind of factual information that was designed to be tapped by the party promise questions or the economic and social condition questions. Furthermore, many participants already self-reported relatively high confidence in their ability to make a good voting decision.

Next, we dig further into participants' political knowledge by assessing their ability—or willingness—to evaluate the parties and their leaders. To do so, we constructed four outcomes. First, we built an index of participants' ability to rate key traits of each of the five participating party leaders. Participants could indicate yes, no, or unsure in each instance. This index counted the number of instances in which a participant gave either a yes or no answer—that is, when they did not answer unsure. Second, we constructed an index to capture participants' ability to rate all five participating leaders on a 0-100 feeling thermometer scale. Here participants could rate each leader or indicate that they "Don't know the leader." We thus computed, for each participant, whether or not they rated all five leaders. Third, we constructed an index of participants' ability to rate the five participating parties on a 0 to 100 feeling thermometer scale. Similar to the leader feeling thermometers, the party feeling thermometers allowed participants to either give a score or to tick "Don't know / Prefer not to answer." Thus, we computed—again for each participant—whether or not they rated all five parties. Fourth, we conducted a similar exercise with respect to participants' ability to place all five parties along the conventional left-right spectrum of political ideology. Here again participants had the option of ticking "unsure" for each party. We computed whether participants placed all five parties along this left-right continuum.

Figure 25 reports the model predictions for the change in each of these four indexes—again for both watchers and non-watchers. We find that debate watching had a statistically significant positive impact on the ability to rate all five leaders using the 0 to 100 feeling thermometer. More specifically, those who watched a debate experienced a 9 percentage point greater increase in net ability to rate the favourability of the leaders—compared to those who did not watch. We do not find statistically significant differences with respect to the other three indexes: the ability to evaluate leaders' traits, the ability to rate the favourability of all five parties, or the ability to place all five parties along the left-right ideological spectrum.

In sum, our analysis did not find debate impacts in the form of knowledge of party promises or factual knowledge about current conditions—nor with respect to participants' ability to rate or situate the parties. We did, however, find some evidence that debate watching led to participant learning about the party leaders: specifically, debate watchers were better able than non-watchers to rate their favourability toward all five participating party leaders. This greater familiarity with the party leaders is notable in that prior research shows that leader evaluations are an important ingredient in voting behaviour. Thus, in our judgment, the question is not whether debates contributed to greater political knowledge: we find that they do. Rather, the question is how best to optimize learning. For example, how can debates be designed in ways to provide the most useful information to Canadians in a short period of time? We turn in Section 4.7 to examining how Canadians' preferences for various debate formats could inform such a design.

4.6.3 On political evaluations

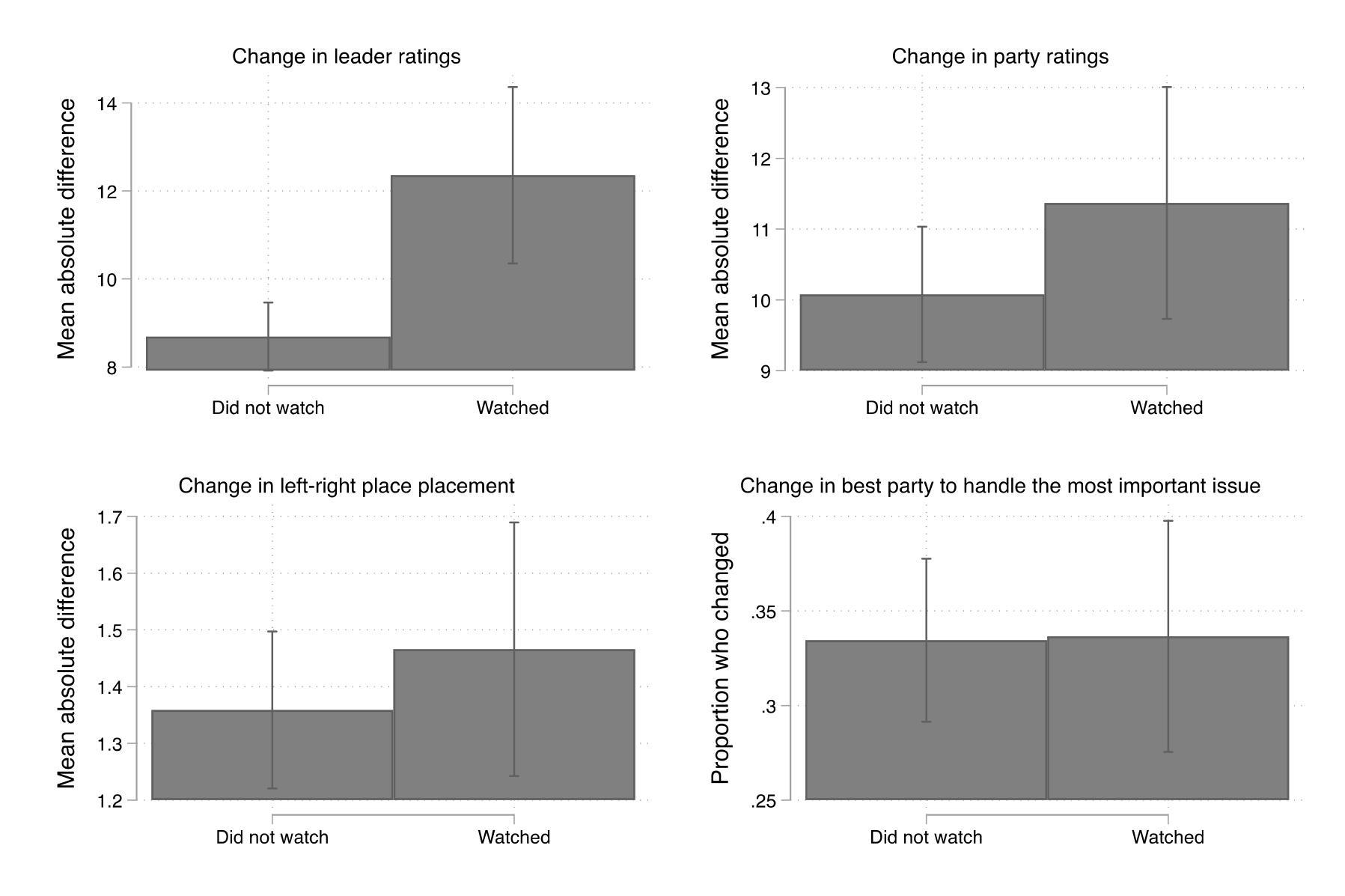

Next, we investigate the influence of debates on citizens' assessments of the leaders and their parties. This serves as a companion to the preceding exploration of Canadians' ability/willingness to rate and place the leaders and their parties. Here we construct four outcome measures. The first three simply capture the within-individual changes in ratings and placements conditional on giving a rating or placement. More specifically, for each participant, we computed (1) the mean absolute difference across the five leader feeling thermometers; (2) the mean absolute difference across the five party feeling thermometers; and (3) the mean absolute difference across the five party left-right ideological placement scales. The fourth measure captures participants' belief about which party was "best at addressing" what they considered to be the most important issue in the election. The measure is thus a simple binary indicator of whether a participant selected a different party in the post-debate second wave than they did in the pre-debate first wave. In short, the four measures capture the degree to which Canadians changed their views of the leaders and parties—without specifying the direction of that change. The results are compiled in Figure 26.

We find that debate viewership contributed to greater change in the leader feeling thermometer ratings. The typical non-watcher updated their mean rating of the leaders by 9 points (recall that the original rating scale was 0 to 100). By contrast, the typical watcher updated their mean leader rating by 12 points, a statistically significant difference. We do not find statistically significant differences between watchers and non-watchers for the other three measures: namely, with respect to party ratings, party left-right ideological placements, or the party believed to best handle the most important issue.

4.6.4 On institutional evaluations

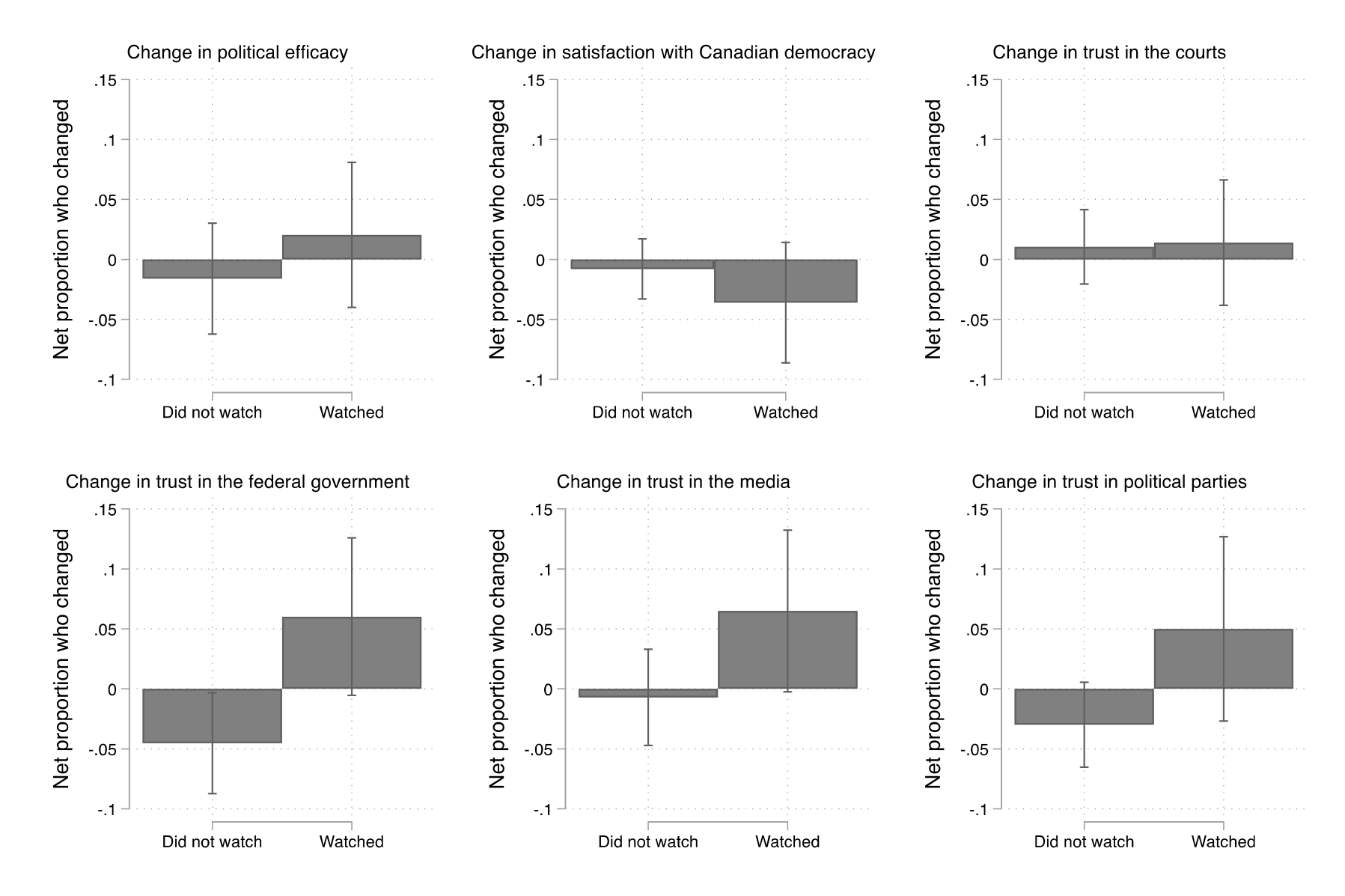

Turning to institutional evaluations, we examine the possible impacts of the debates on participants' self-reported political efficacy and satisfaction with Canadian democracy—as well as the degree to which they trust key political institutions like the courts, the federal government, the media, and political parties.

The results are reported in Figure 27. We find evidence that the debates had a positive impact on trust in the federal government. Compared to those who did not watch, debate watchers experienced a 10 percentage point greater net increase in trust in the federal government. We also find some evidence of greater increases in trust in the media and trust in political parties among watchers—again relative to non-watchers—though this difference only approaches the conventional level of statistical significance (in the case of both outcomes, p = .07). We do not find evidence that debate watching contributed to increases in political efficacy, satisfaction with Canadian democracy, or trust in the courts.

The fact that debate watching contributed to increased trust in the federal government, and possibly also to increased trust in the media and political parties, is notable and worth considering further. Indeed, one would not necessarily expect that exposure to the often combative and partisan atmosphere of a debate would build public trust. One possible explanation, however, is that seeing the leaders, including the prime minister, subject to questioning and compelled to explain themselves serves to engender greater trust. Future research should go deeper on this question of trust, exploring what particular features of debates help build Canadians' confidence in their political institutions.

4.6.5 On political behaviour

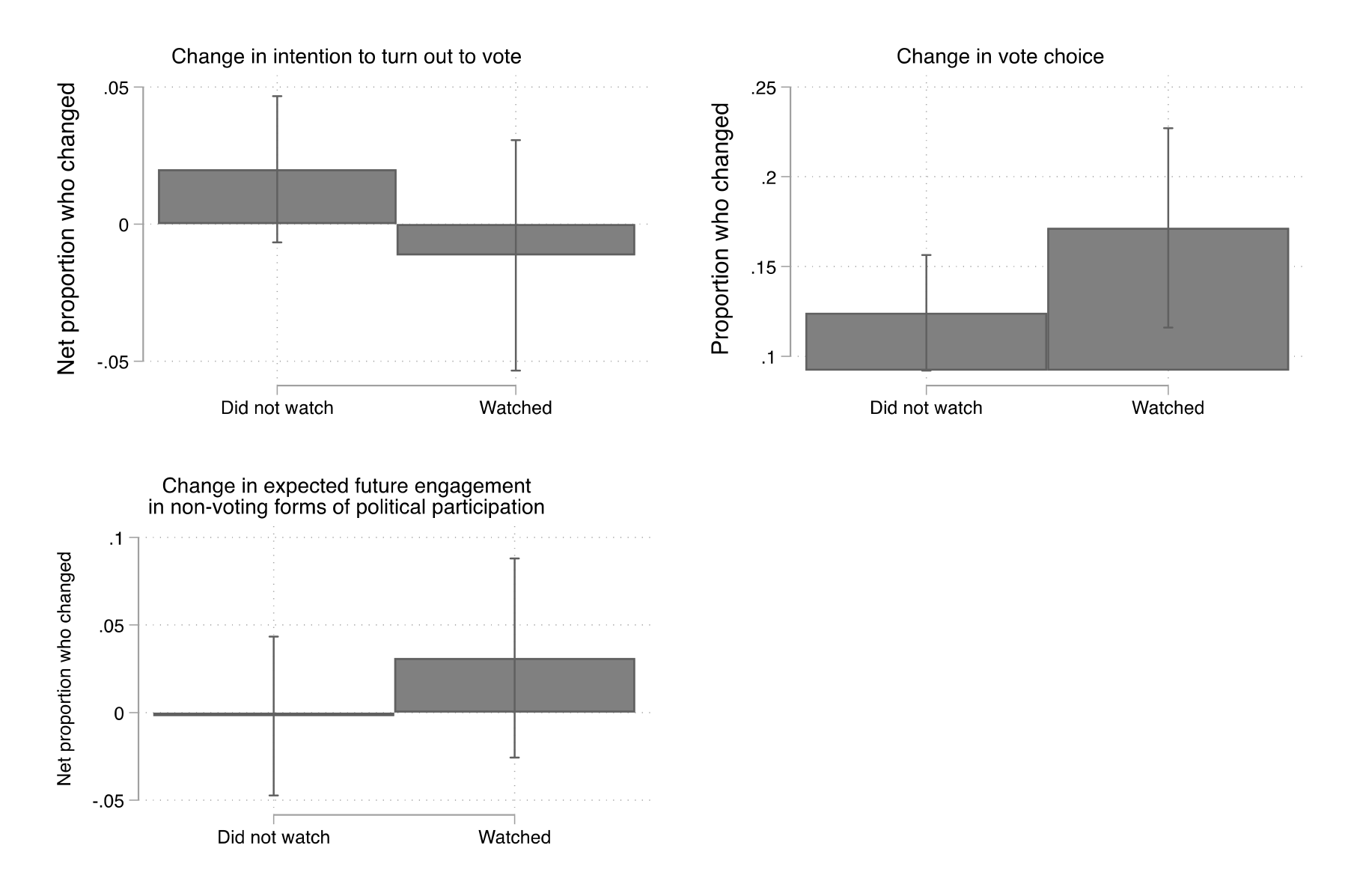

The last set of outcomes we explore concern political behaviour—specifically in terms of 2021 turnout intention and vote choice, as well as participants' expectations about their future non-voting forms of political participation. These are reported in Figure 28. We do not find evidence that debate watching was associated with changes in these behaviours at conventional levels of statistical significance.

4.7 Public preferences for future debates

In this section, we turn to investigating Canadians' preferences for future debates. To estimate these preferences, we administered a third survey to a fresh cross-section of just under 500 Canadians. The survey elicited views across a wide range of issues—ranging from who should participate in the debates to how the debates should be moderated to the appeal of various different types of debates and public events. These preferences were gauged in a variety of ways: for example, by asking participants to rank their goals, to make trade-offs between debate formats, and to allocate a time budget within a given debate. What emerges, we believe, is the most comprehensive picture available of Canadians' preferences for leaders' debates.

4.7.1 Goals of leaders' debates

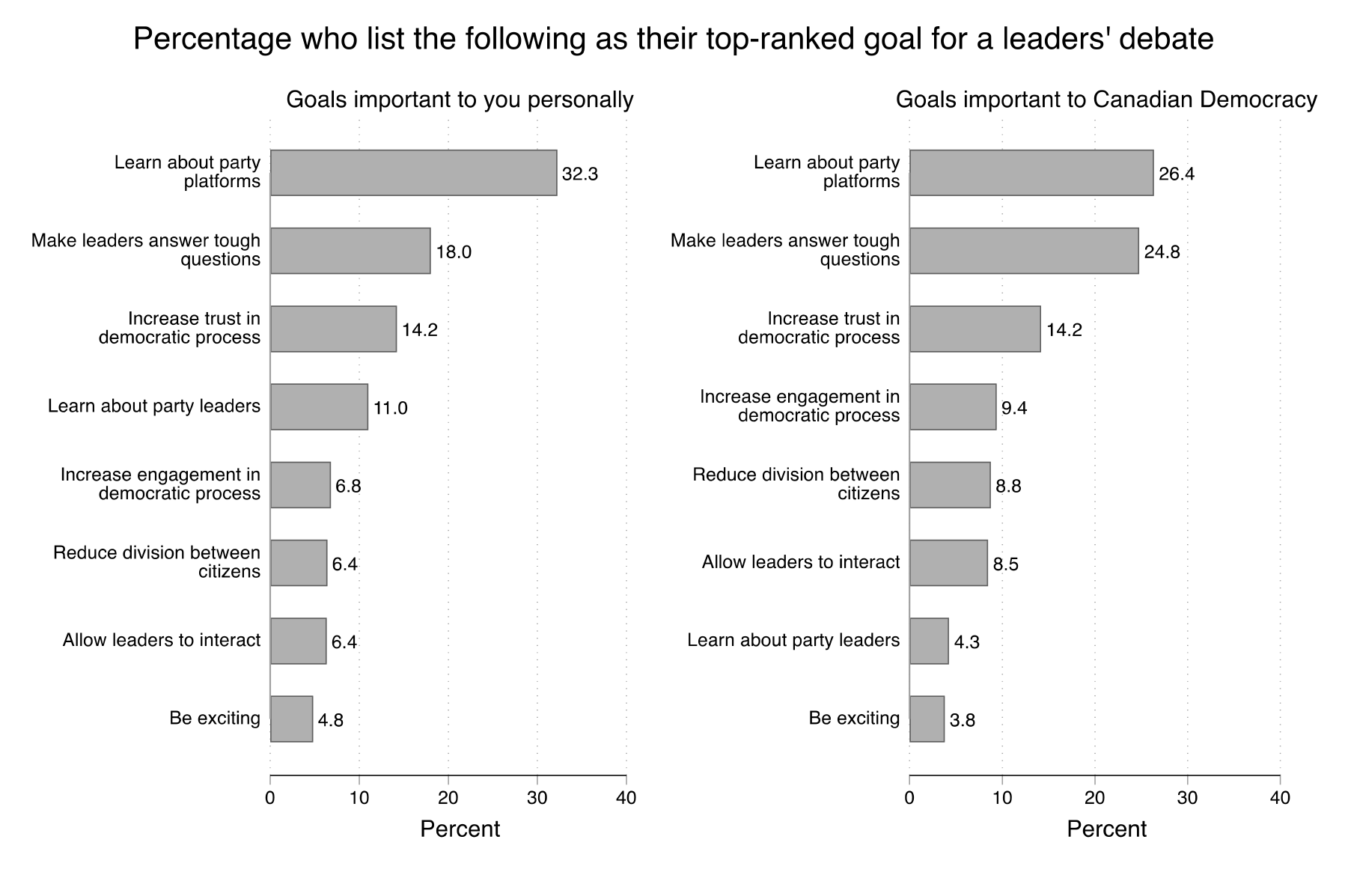

We begin our exploration of Canadians' preferences from first principles: by asking participants to rank their top three goals from a pre-established set of possible goals for a leaders' debate. Half of the sample was randomly assigned to a prompt that asked them to rank the top three that were "most important to you personally," while the other half was randomly assigned to a prompt that asked them to rank the top three that they thought were "most important to Canadian democracy." In this way, we gain a window into whether Canadians' personal goals for leaders' debates differ from how they think the public interest should be served by the debates.

The results are presented in Figure 29. We report the percentage of participants who ranked the given objective as their top goal. The results are disaggregated by whether the participant was prompted to think about what was important to them personally (left) and what was important to Canadian democracy (right).

We highlight four findings. First, the most common top-ranked goal was to "Help citizens learn about the parties' platforms and promises." Roughly one-third (32%) of those in the "goals important to you personally" condition ranked this as their top goal, as did just over one-quarter (26%) of those in the "goals important to Canadian democracy" condition. Notably, however, not all learning goals were considered equal: far fewer participants in each condition identified helping "citizens learn about the party leaders" as their top ranked goal.

Second, the next most common top-ranked goal was to "Make party leaders answer tough questions." This was again the case regardless of question prompt. Debates as an exercise of accountability features prominently in Canadians' preferences. Third, a sizeable fraction of participants sought a debate that served to "Increase citizens' trust in the democratic process"—the third most common top-ranked debate goal (14% in each condition). We noted in Section 4.6.4 evidence that the 2021 debates did increase some forms of institutional trust—despite, or perhaps because, they at times incentivized conflict and opposition. We believe that further research can help inform debate designs that serve to make leaders answer difficult questions while still building trust in the democratic process.

Fourth, we highlight that 'debate as entertainment' holds little appeal for citizens. Less than 5% of participants reported that their top-ranked goal was for a debate to be "exciting." Similarly, relatively few citizens identified seeing the leaders interact as a key goal of a debate. This comparatively low priority for interaction as such mirrors the recurring distaste of focus group participants for debate segments that allowed the leaders to talk over each other. While debates provide a rare opportunity for leaders to interact, the results here imply that Canadians do not find this interaction an especially desirable end in itself. Nevertheless, leader interaction can still be put in service of other goals—such as promoting learning about party platforms and holding leaders accountable—provided that it is done in a manner that ensures that leaders speak only one at a time.

4.7.2 Leader participation

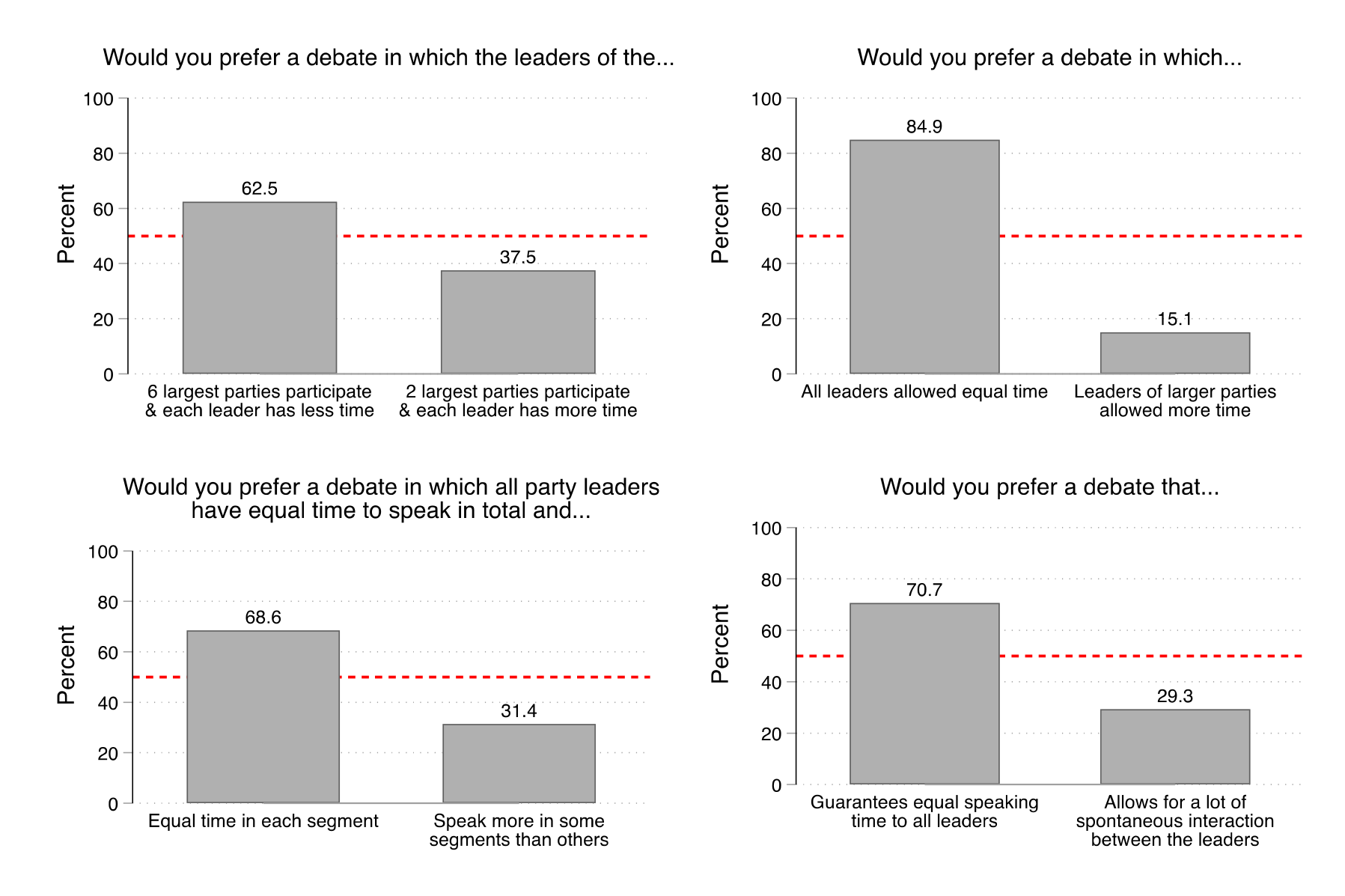

Next, we turn to examining citizens' preferences for leader participation within the context of a single debate. Canada has many political parties and deciding which party leaders to invite to a debate is necessarily a judgment call that is, understandably, a source of political contestation. We explored Canadians' preferences first using a series of four binary choice questions. For each question, participants are presented with two hypothetical debates and asked to choose which they prefer.

The results are reported in Figure 30. Two findings stand out. First, when presented with a hypothetical debate in which the leaders of the "six largest parties are invited to participate - and each leader has less time to speak" and a hypothetical debate in which the leaders of the "two largest parties are invited to participate - and each leader has more time to speak," 62% of participants chose the former. It is worth underscoring that this choice was made in full knowledge of the likely trade-off: namely, that more leaders would mean less time for each leader to speak.

Second, participants strongly preferred—at least in the abstract—an equal allocation of speaking time between those leaders who are invited to participate in a debate. A very large majority (85%) preferred a debate in which all leaders were allocated equal time to a debate in which the leaders of the larger parties received more speaking time than the leaders of the smaller parties. This preference for equal treatment holds not simply for the debate as a whole: a large majority (67%) preferred a debate in which all leaders have equal time in each segment to a debate in which the leaders speak more in some segments than others—even though, by construction, both options were presented as providing equal time in total to the leaders. Furthermore, another large majority of Canadians appears willing to trade spontaneity for equal time: 71% favoured a debate that "guarantees equal speaking time to all leaders - even though this means only a little time for spontaneous interaction between the leaders" to a debate that "allows for a lot of spontaneous interaction between the leaders - even though this means they may not have equal speaking time."

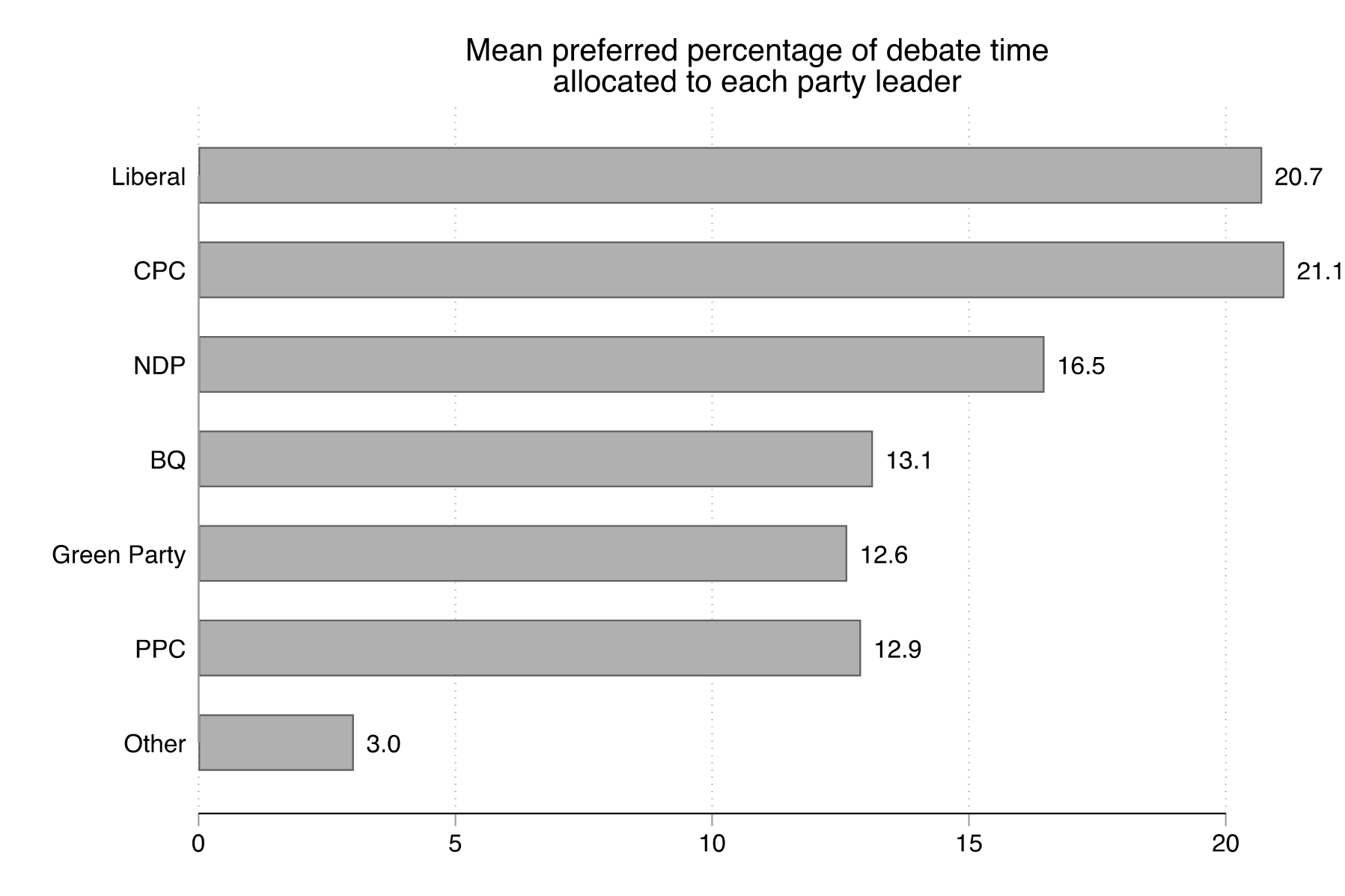

We further probed Canadians' preferences for how time should be allocated between party leaders by making the available choices more concrete. Elsewhere in the survey, participants were asked to imagine that they were responsible for organizing one, two-hour debate during the next federal election and that their job was "to decide how best to divide up this time." They were asked to assign a percentage of time to each leader. Participants could assign a value from 0% to 100% for each leader—provided that the total allocations summed to 100%.

Figure 31 reports the mean percentage of debate time that participants allocated to each leader. The results suggest that, when this task is made more concrete, we do see some evidence of departures from perfect equality. The mean allocation for the two largest parties—the Liberals and the Conservatives—was in the order of 21% of the available time, while the mean allocation for the three smallest parties—the BQ, the Greens and the PPC—was in the order of 13% of the available time. The NDP fell between these two sets with a mean allocation of 17% of the available time.

While there are noticeable differences in allocation between some of these parties, it is worth recognizing that the substantive departure from equality remains relatively modest. Consider that perfect equality between six parties (setting aside the unspecified "Other" in the question) would imply a 100/6 = 17% allocation for each party. Thus, the mean allocation for the two largest parties is only 4 percentage points higher than perfect equality and the mean allocation for the three smallest parties is only 4 percentage points lower than perfect equality.

4.7.3 Moderation and the sources of questions

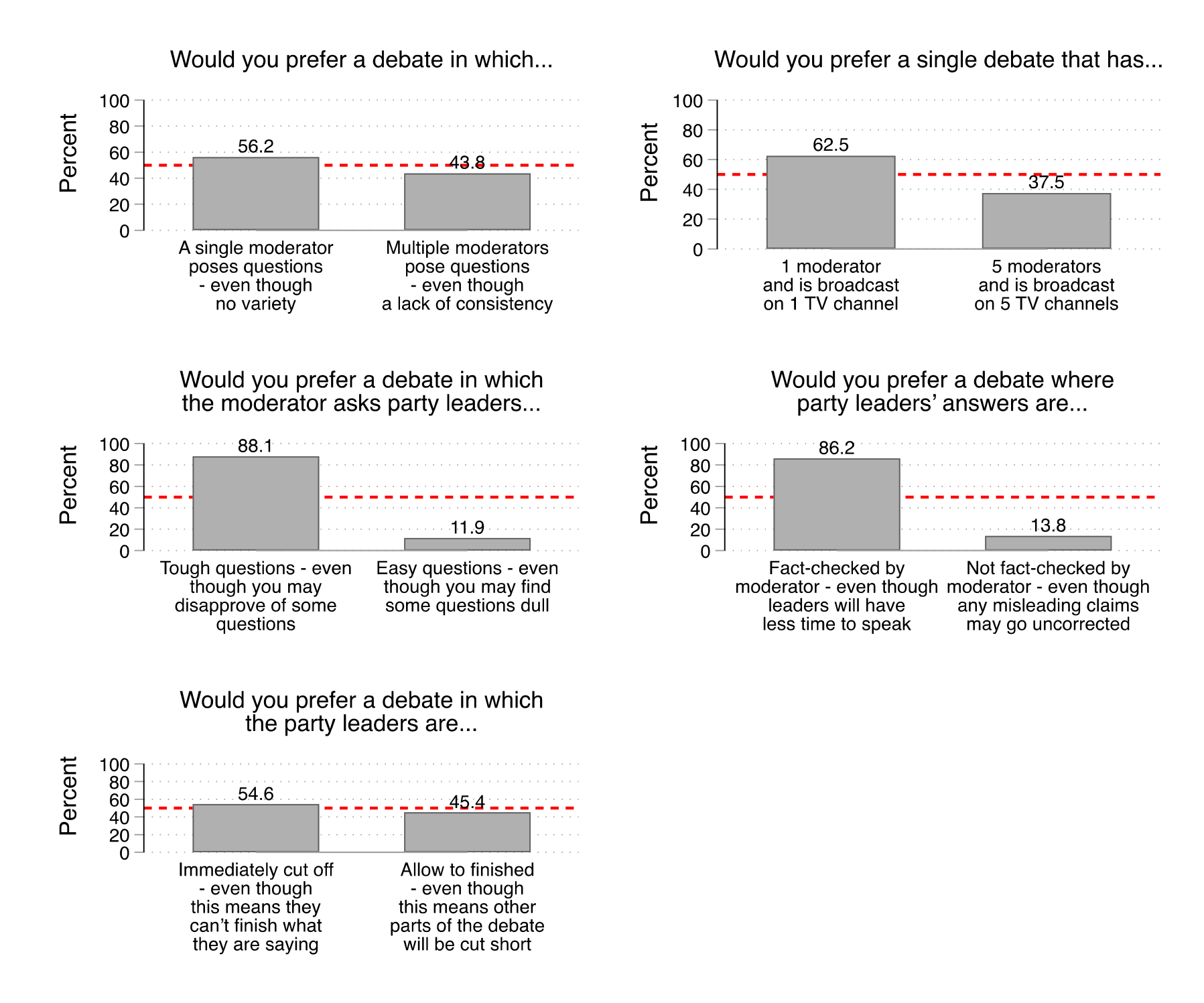

A key design consideration of many modern leaders' debates is the nature of the moderation and, more broadly, of the sources of the questions put to the party leaders. We approach this again from multiple perspectives: by asking participants to choose between hypothetical pairs of debates that differ with respect to the moderation; by asking participants what they believe a moderator's role should be; and by asking participants to allocate a share of questions according to their preferred sources (e.g., the moderator, the public, journalists, etc.).

Figure 32 presents five sets of binary choices. We highlight three findings. First, Canadians strongly prefer a debate in which the moderator provides an accountability role to one in which the moderator takes on a more limited role. Nearly nine in ten (88%) preferred a debate in which the moderator asked the leaders "tough questions - even though this means you may disapprove of some of the moderator's questions" to a debate where the moderator asked "easy questions - even though this means you may find some of the moderator's questions dull." It is worth underscoring that this preference for "tough questions" came with the understanding that they, as viewers, might disapprove of some of the questions. A similarly large majority (86%) favoured a debate in which the moderator served as a fact checker—even though this role came at the price of less speaking time for the leaders.

Second, more modest majorities favored a debate with a single moderator to a debate with multiple moderators—regardless of whether this choice was framed as a trade-off in terms of variety or a tradeoff in terms of channel access. For example, 63% favoured a debate with a single moderator that was broadcast on a single channel to a debate with five moderators that was broadcast on five channels.

Third, Canadians were relatively evenly split about how to manage leaders who might exceed their allotted time. Just over half (55%) preferred a debate in which the party leaders are "immediately cut off when they reach their time limit - even though this means they can't finish what they are saying" to one in which the leaders are "allowed to finish what they are saying - even though this means that other parts of the debate will be cut short to make up for lost time." This split, we believe, reflects the views of many focus group participants who thought that cutting leaders off was impolite—while still recognizing that some kind of cut off was a 'necessary evil.' Future debate organizers may wish to reflect on how they can simultaneously pursue a debate in which time is closely regulated (per the public's preference for equal time between leaders) while still minimizing the need for—or the obtrusiveness of—cutting off leaders who run long.

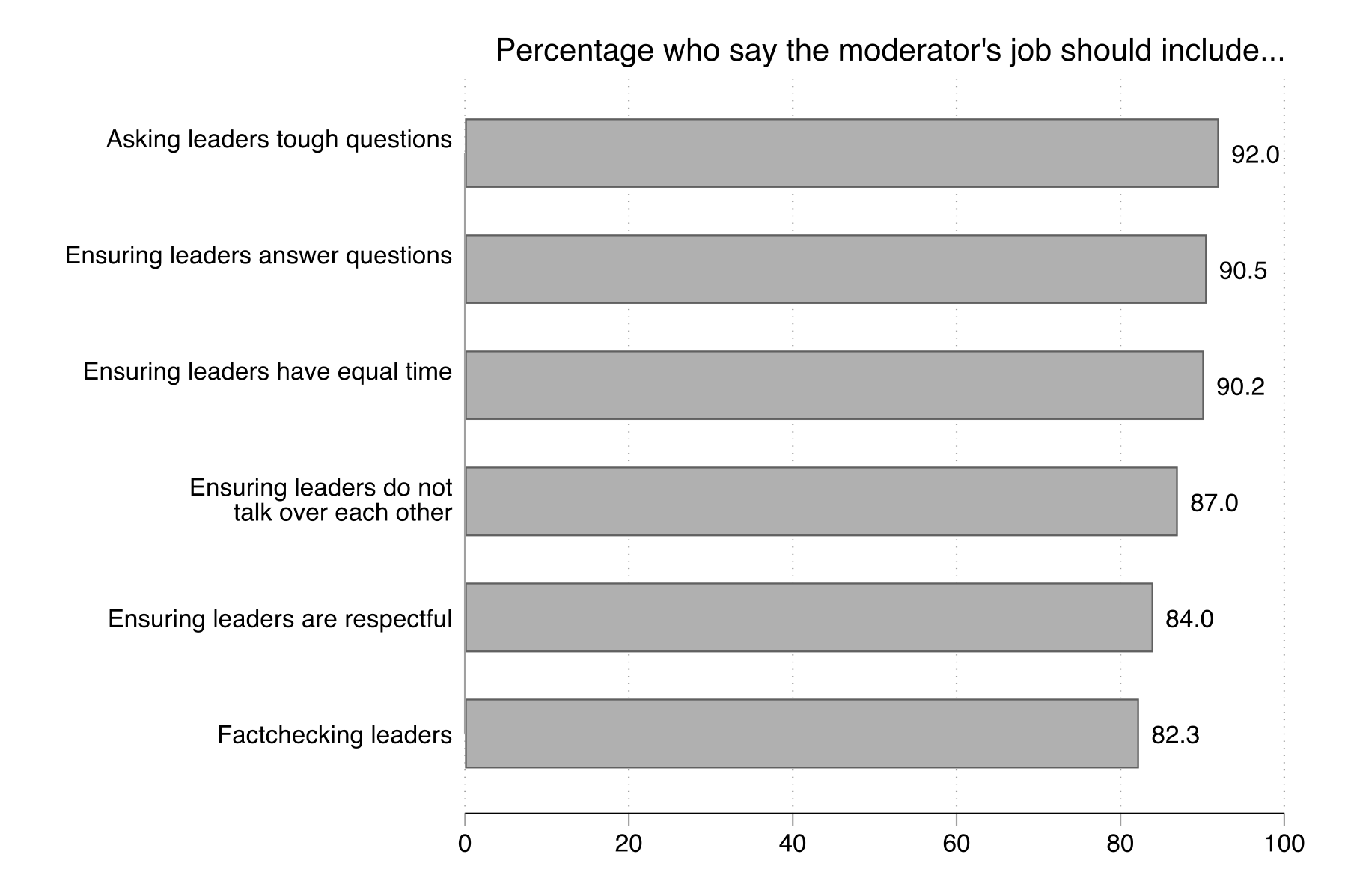

Next, we turn to what Canadians think are the appropriate roles for a debate moderator. In this question, participants were presented with a list of six possible roles and asked which they thought should be part of a moderator's job. The results, presented in Figure 33, are striking. In each instance, no fewer than four in five felt that each role was indeed part of the moderator's job. The public's aggregate preference is thus far from 'laissez-faire' moderation. Very large majorities want the moderator to ask tough questions of the leaders; to ensure that the leaders answer these questions; to enforce equal time among leaders; to make sure the leaders do not talk over each other; to ensure the leaders are respectful of each other; and to fact-check leaders' answers. In short, most Canadians want the moderator to be a key actor in the debate through promoting accountability and ensuring fair play.

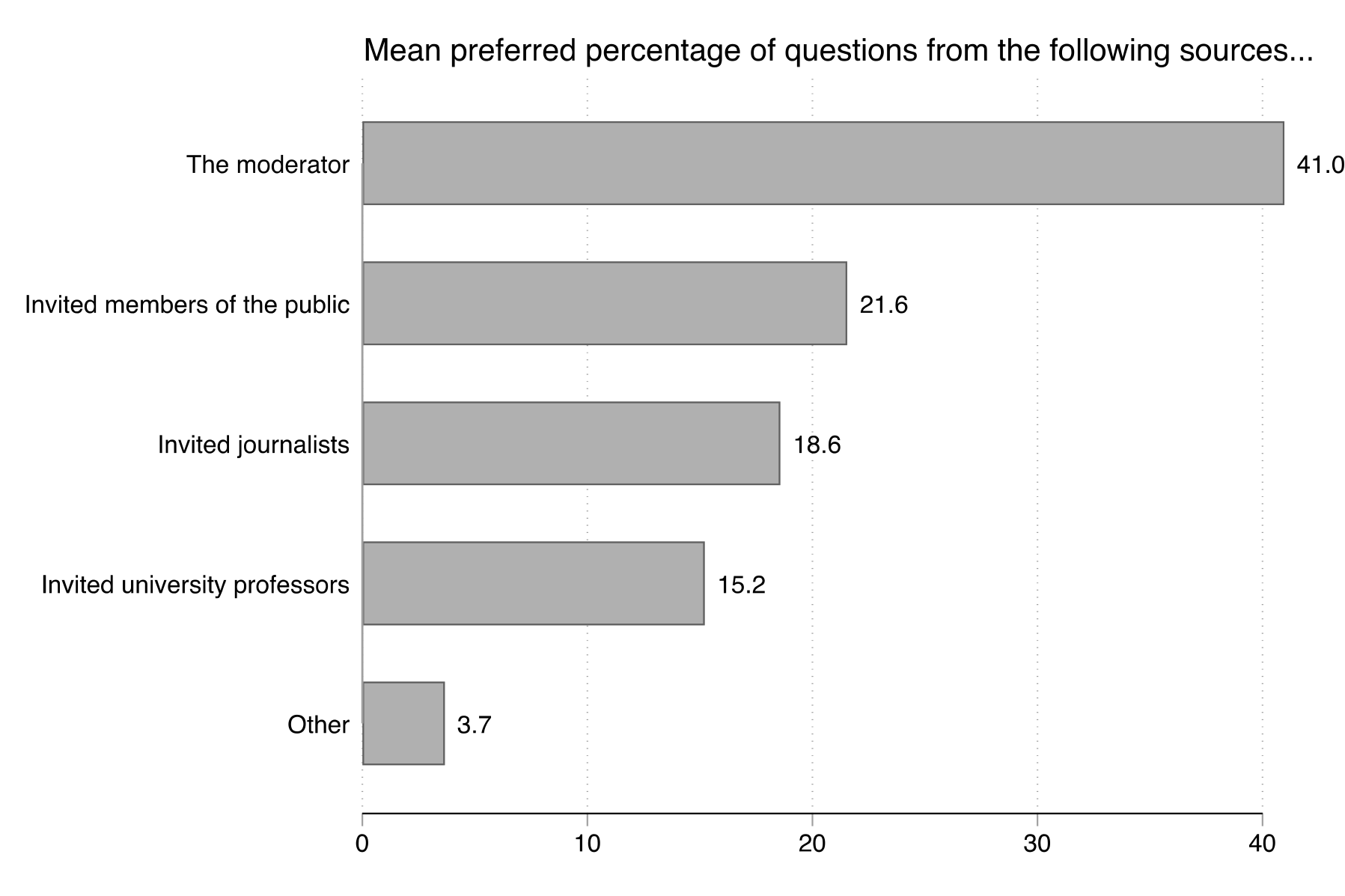

The moderator is not the only possible source of questions put to the leaders in a debate. Indeed, the 2021 debates included questions from other sources: journalists were invited to ask questions live, as were a handful of members of the public. How do Canadians feel about these sources? To answer this, we again asked participants to undertake a constrained allocation task: that is, to assign a percentage of questions to various possible sources. Participants could allocate anywhere from 0 to 100% of questions to a given source—provided that the total allocations summed to 100%.

Figure 34 reports the mean percentage allocated to each source. Canadians, on average, wanted the moderator to ask the most questions: roughly 2 of every 5 questions. Next, participants, wanted to see members of the public asking 22% of questions on average—slightly ahead of journalists at 19%. For comparison, we included "university professors" as a possible question source—though this is not a common practice in federal leaders' debates in Canada. Of the available sources, professors were the least popular—allocated only 15% of questions on average. These results largely echo the preceding findings: Canadians see a vital role for the moderator in a debate, but also seek to reserve some space for the public and for other journalists to put their questions.

4.7.4 Debate topics

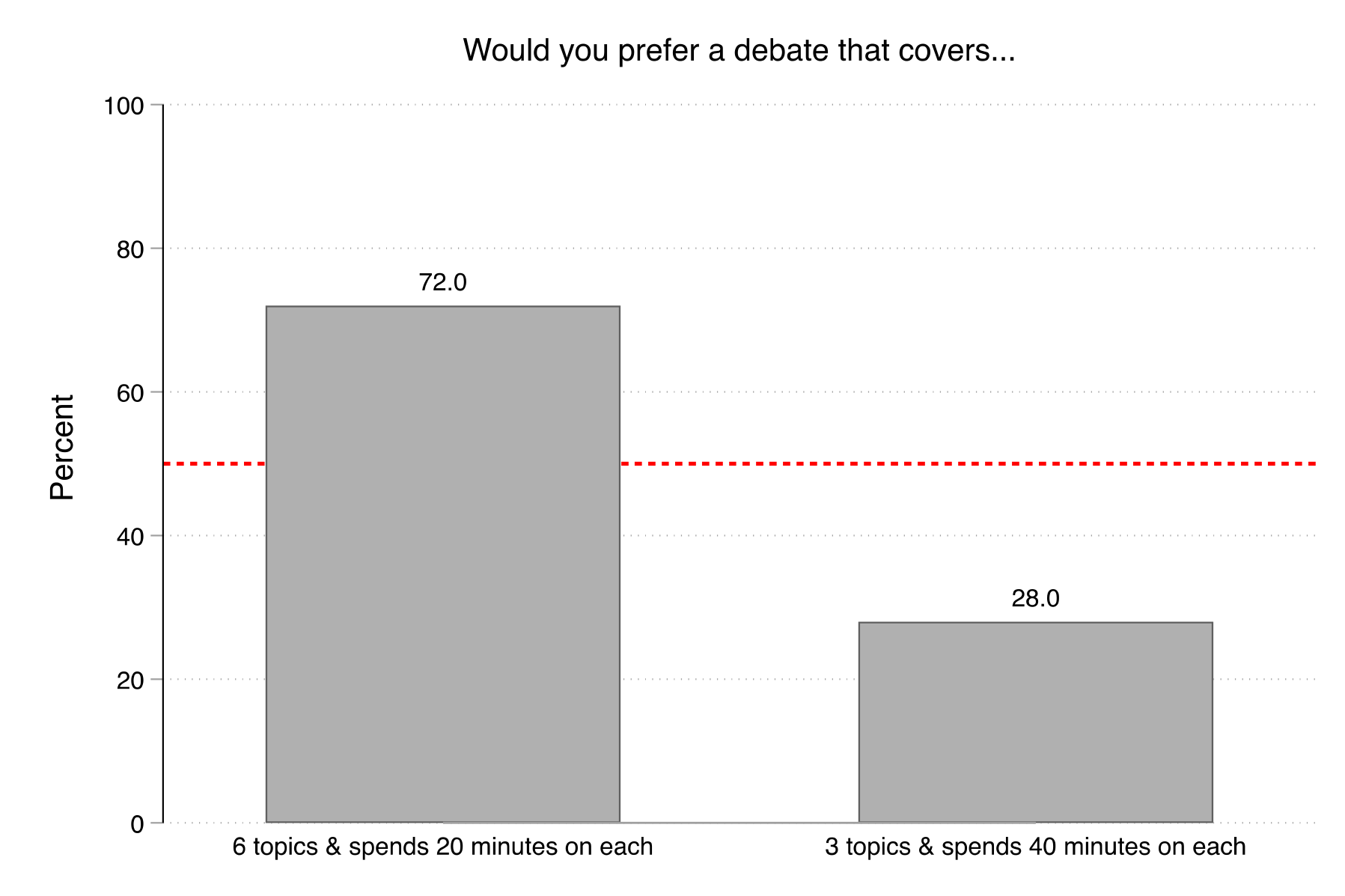

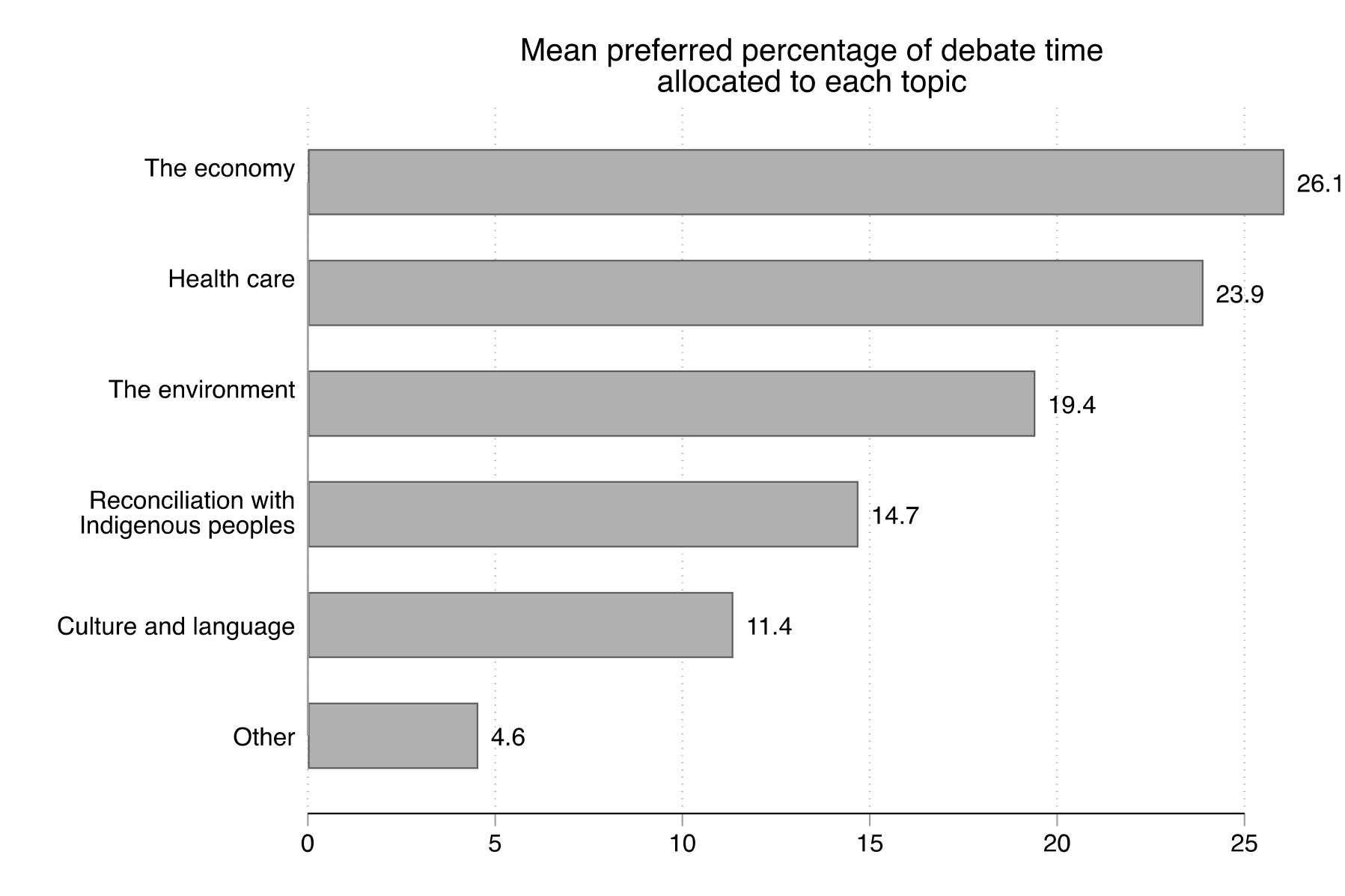

The choice of topics is another crucial ingredient in any debate—not least because, as noted in Section 4.5.1, many viewers of the 2021 debates found that these events did not cover the issues that were most important to them. Indeed, satisfying the diverse interests of the Canadian public in a two-hour period is a significant challenge. The choice of topics requires balancing at least two important considerations: the number of topics and the depth of discussion of each. While including more topics in a given debate help it cover the issues of interest to more Canadians, this may come at the price of depth—reducing the time available to cover the party platforms in the detail that Canadians want.

We put this tradeoff to survey participants—asking which they would prefer: a debate that covers "3 topics and spends 40 minutes on each topic" or a debate that covers "6 topics and spends 20 minutes on each topic." The results are reported in Figure 35. Nearly three-quarters preferred the six-topic debate. (In Section 4.7.8, we explore the appeal of single-topic debates in the context of possible campaigns with more than one debate in each official language.)

We also probed the preferences for debate topics further with another time allocation task—again asking participants to divide up the available time of a single debate between a set of five pre-selected topics. Figure 36 reports the mean percentage of debate time allocated by participants to each topic. The results confirm the appeal of a debate with several topics, while also suggesting an openness to allocating more time to some topics than others.

4.7.5 Debate formats

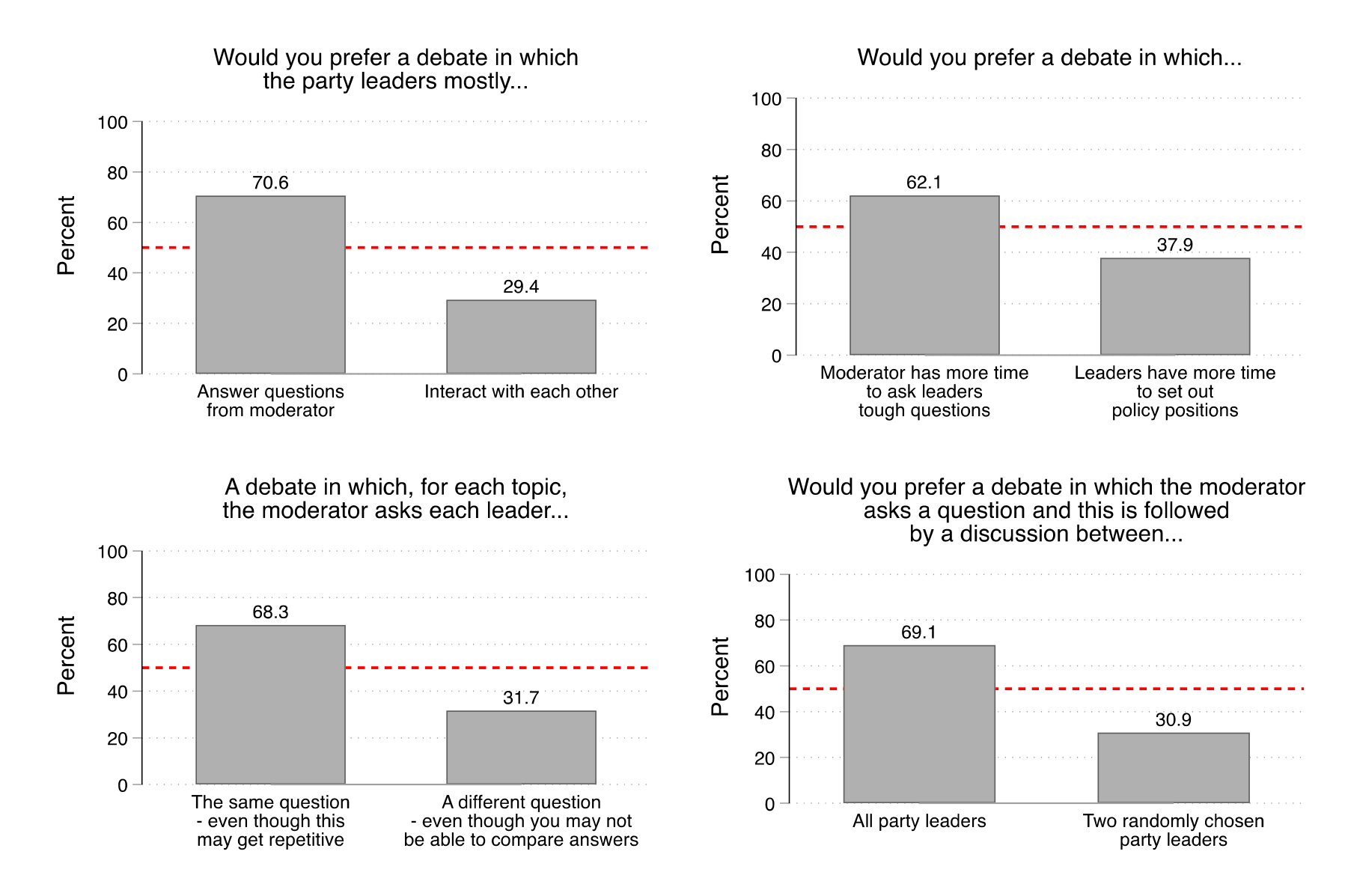

Format has an important bearing on the conduct of any debate and potentially influences how debates can achieve Canadians' top ranked goals of learning about the parties, holding leaders accountable, and building trust in the democratic process. We begin our exploration with four binary questions pertaining to debate format. For each question, participants were again asked to choose which of the two hypothetical debates they preferred. The results are reported in Figure 37.

We make four findings. First, over seven in ten (71%) favoured a debate in which the leaders mostly answered questions from the moderator over a debate where the leaders mostly interacted with each other. Second, a majority (62%) again favoured the moderator-centered questioning model over a model in which leaders have more time "to set out their policy positions in detail." Third, with respect to the moderators' questions, just over two-thirds (68%) favoured asking each leader the same question "even though this may get repetitive" over a debate in which the moderator asks each leader a different question. Fourth, following on this same theme, we find that 69% of Canadians favoured a debate in which the moderator poses a question and the ensuring discussion includes all party leaders—compared to a debate in which the ensuing discussion involves only two leaders chosen at random. While the random selection of leaders is a common strategy for managing some parts of a debate, Canadians again appear to prefer greater inclusion—a preference that reflects their commitment to the equal participation of leaders noted earlier. The challenge remains how to build an inclusive debate featuring several party leaders, while still avoiding situations where the leaders talk over each other.

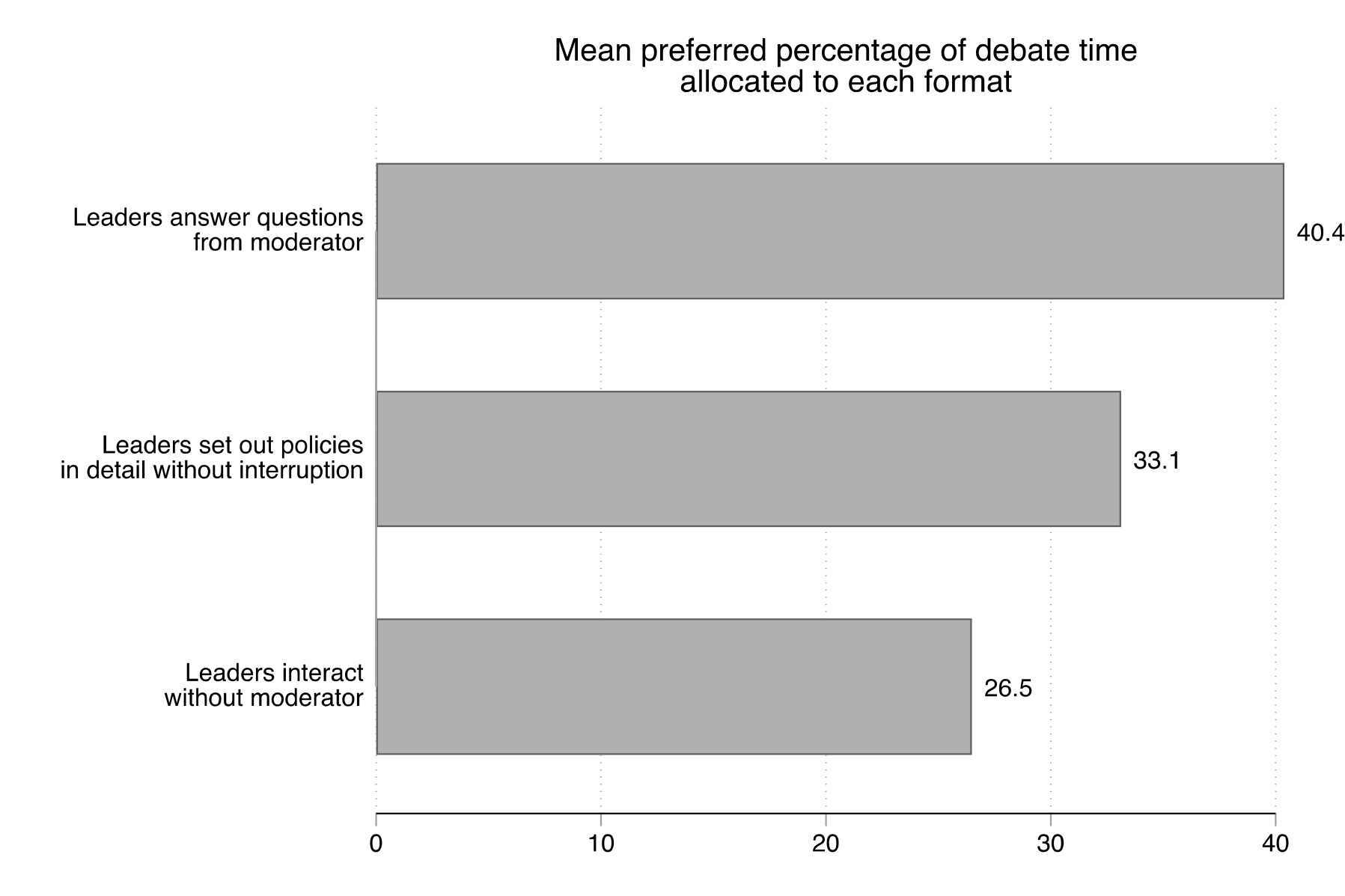

To explore these format preferences from a different perspective, we again asked participants to engage in a time allocation task for a single, two-hour debate in the next federal election. Participants were asked to allot time across three possible formats: (1) "The party leaders answer questions asked by the moderator"; (2) "The party leaders interact with each other without the involvement of the moderator"; (3) "The party leaders set out their policy positions in detail and without interruption." Participants' responses were constrained such that the total of the allotted percentages summed to 100. The results are reported in Figure 38.

Echoing previous results, a moderator-centric format received the greatest time allocation. Participants on average assigned 40% of the debate time to having leaders answer questions from the moderator. Having said this, participants on average still reserved a third of the time for the leaders to set out their policies without interruption. This format also reflects comments from some focus group participants who wanted debates as a means of efficiently getting up to speed on what the parties were promising during the campaign. Lastly, just over a quarter of the time (27%) was allocated on average to leaders interacting without the moderator. While we find that this kind of interaction was not a leading goal for the debates as such, Canadians may understandably see between-leader interaction as facilitating the kind of learning and accountability they are looking for.

4.7.6 Scheduling the debates

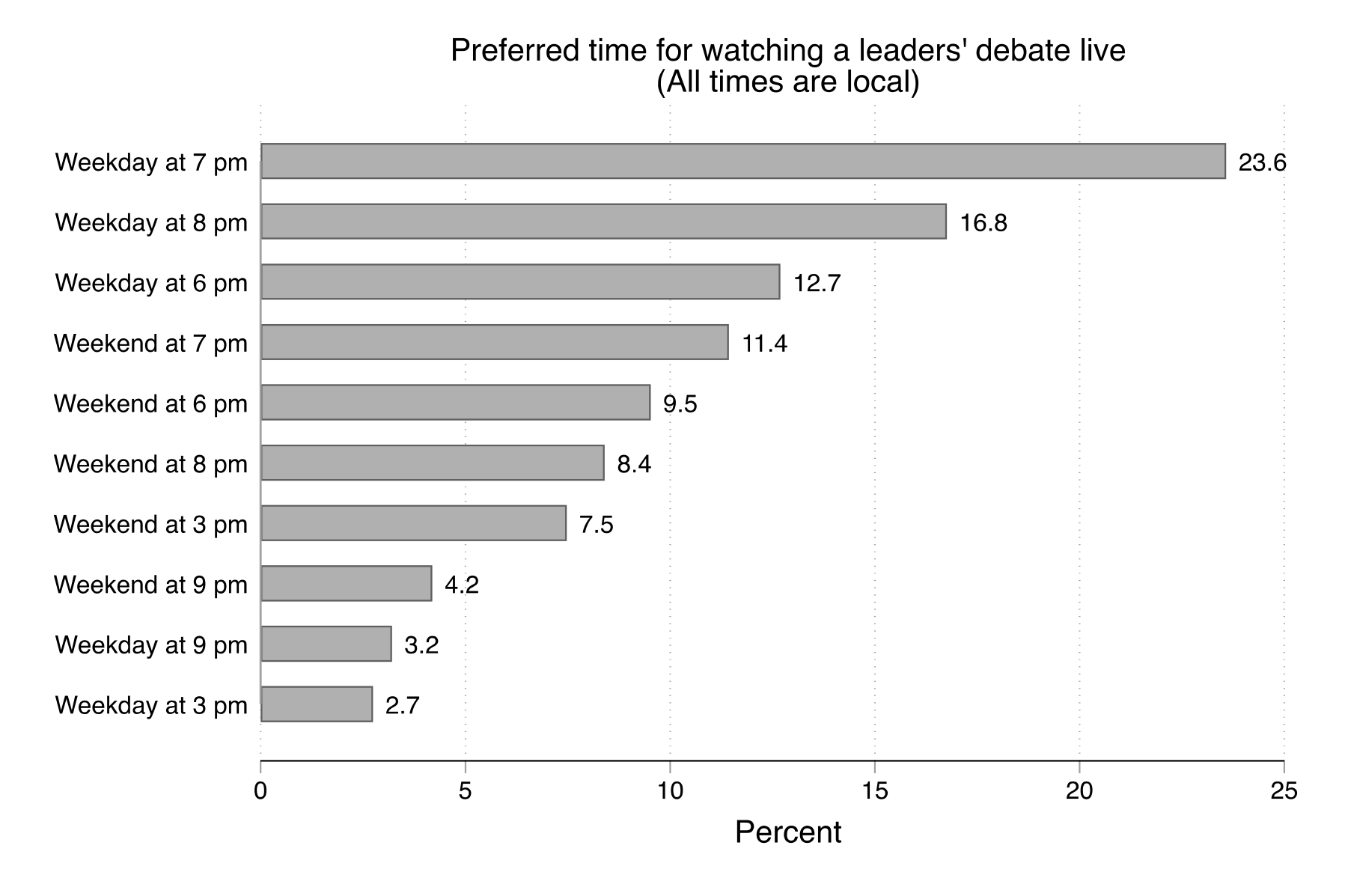

Given that being "too busy" was a common reason for not watching a 2021 debate, we asked participants in the third survey their preference for when to watch a debate live. This was elicited in two steps: first, participants were asked whether they would be more likely to watch on a weekday or a weekend; second, participants were asked their preferred time of day (choosing from 3, 6, 7, 8, or 9 pm ). Participants were informed that all times were local to their area. We combined the answers to the two questions and report the results in Figure 39.

The most popular time to watch a debate live—chosen by 24% of participants—is on a weekday at 7 pm. The next two most popular times were on either side of this time slot: namely, 8 pm and 6 pm weekdays. Notably, the least popular times were those early in the day (3 pm) and late in the day (9 pm)—and this was the case whether the debate fell on a weekday or a weekend.

To be sure, accommodating these scheduling preferences cannot be readily done in the context of a single live debate given Canada's time zones. For example, a weekday debate that starts at 7 pm in the Atlantic time zone (the most preferred time) means a 3 pm start in the Pacific time zone (the least preferred time). Solutions may require further creative thinking that could involve the implementation of regionally-based leaders' debates, the re-broadcast of previously recorded debates in their entirety, or the increased promotion of on-demand clips of the debates through news sites and social media.

4.7.7 Stage arrangements

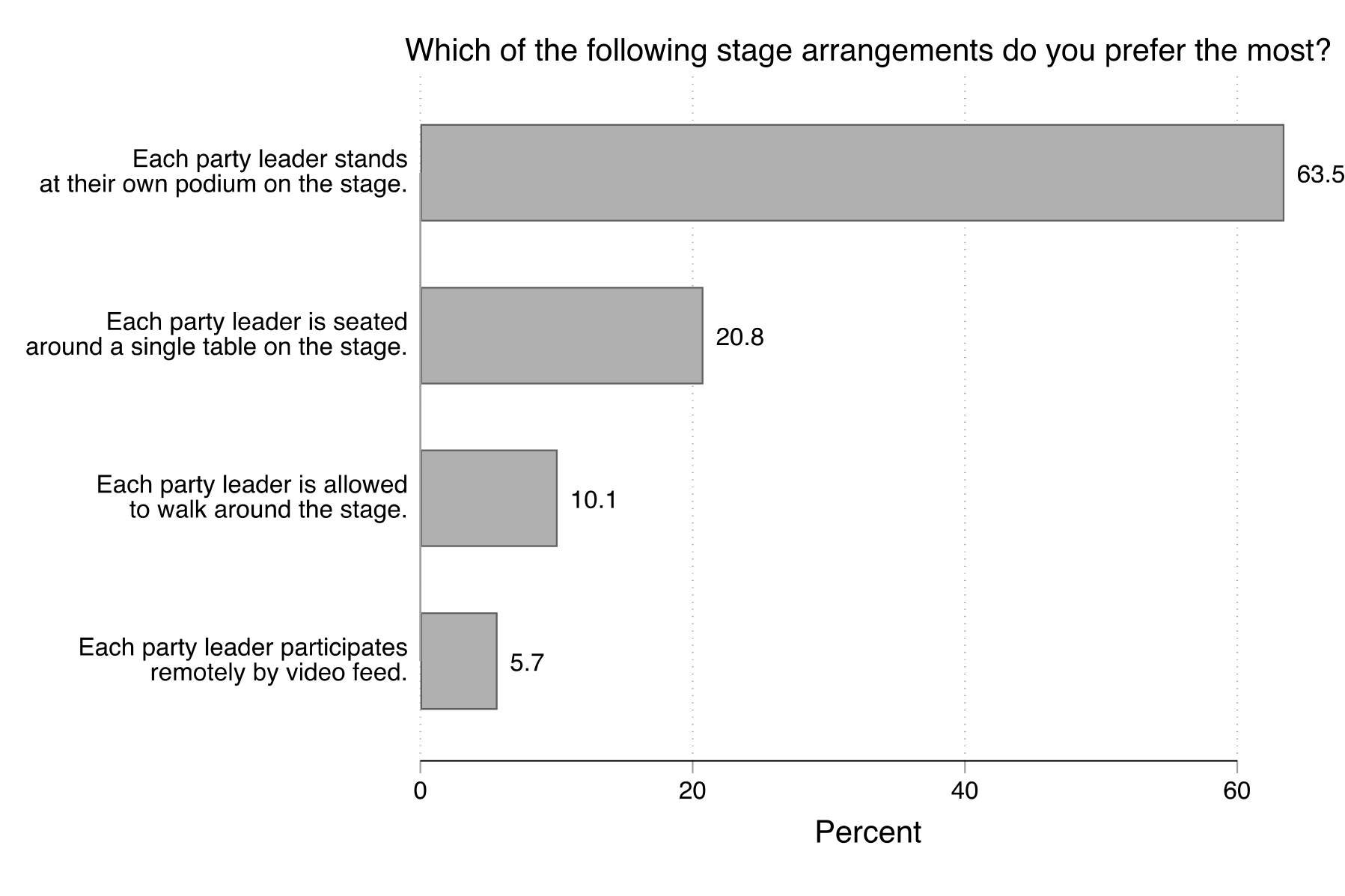

We asked Canadians how they would like the party leaders to be arranged on the debate stage. We provided four possible choices: each leader at their own podium; each leader seated around a single table; each leader allowed to walk around the stage; or each leader participating by remote video feed. Figure 40 presents the results. The clear preference, favoured by nearly two thirds (64%) of participants, was to have each party leader stand at their own podium. The least favoured arrangement was remote video feed.

4.7.8 Number of debates

The final set of findings take up the key question of how many leaders' debates to hold. As noted earlier, a single debate makes the trade-offs with respect to leader participation, topic, format, and even scheduling particularly challenging. In theory, holding more than one debate—as is done in some other jurisdictions—could go some way to relieving these tensions. Do Canadians, however, want more leaders' debates?

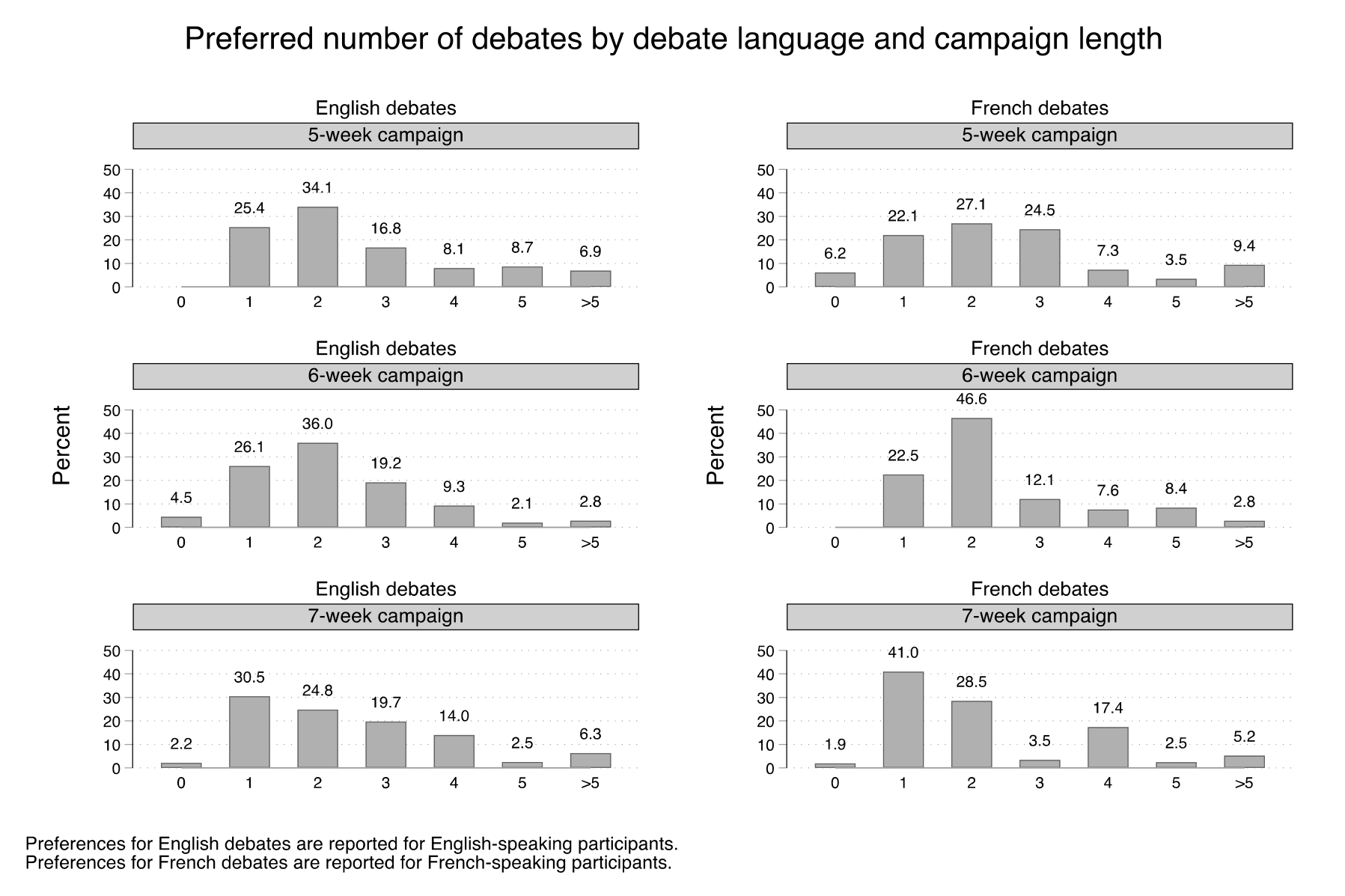

We tackled this question using a variety of approaches. Figure 41 reports Canadians' preferences for the number of debates in each language. Participants could choose 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or more than 5 debates. All participants were asked to choose their preferred number of English-language debates and French-language debates separately; given the intended audience of each debate, we report below the preferences for the number of English debates among English-speaking participants only and the preferences for the number of French debates among French-speaking participants only. Additionally, we randomly assigned all participants to one of three prompts about the length of the campaign. One-third was asked to make their selections when imagining that the next federal election would be five weeks long, another third was asked to imagine that it would be six weeks long, and a final third was told to imagine that it would be seven weeks long. In this way, we can examine whether citizens' preferences for the number of debates varies noticeably as a function of possible campaign lengths.

We make three main findings. First, only a very small proportion of participants wanted no debates at all. Given natural variation in political interest, as well as the negative news commentary that can sometimes accompany leaders' debates, this result is worth underscoring: the vast majority of Canadians want federal election campaigns to include leaders' debates. Second, a majority of Canadians would like to see two or more debates. In each of the six conditions, only a minority favoured one debate. Third, we do not find statistically significant evidence that campaign length influenced preferences for the number of debates. Put another way, the public demand for debates appears to be no weaker in a 5-week campaign than it is in a 7-week campaign.

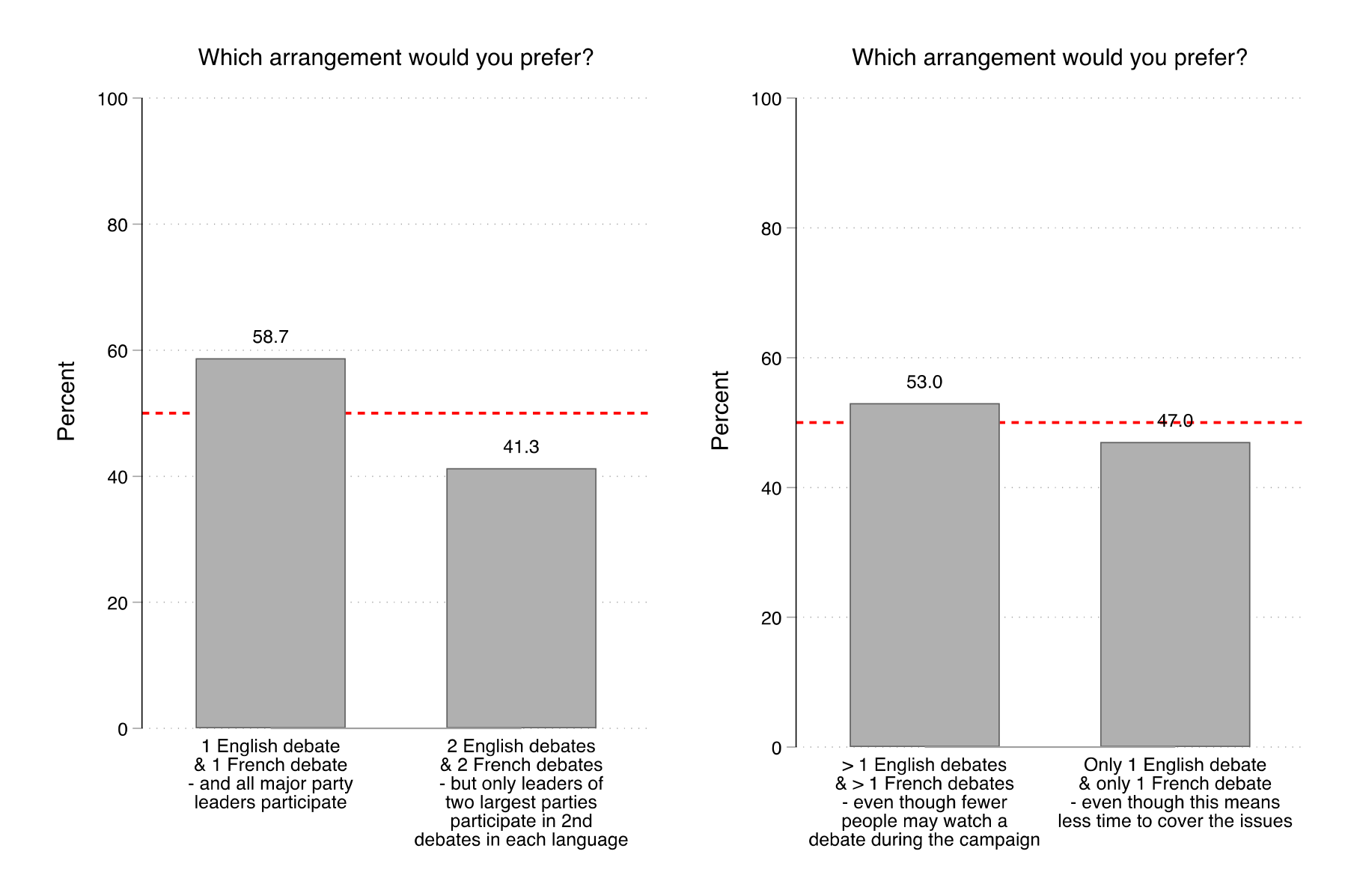

Next, we turn to exploring if these preferences for the number of debates are potentially subject to plausible trade-offs. Here we do so in the context of two binary choices, the results of which are reported in Figure 42. First, we asked participants to choose between two arrangements where: (1) there was one debate in each language and all major party leaders participated; or (2) there were two debates in each language but the second debate in each language included only the leaders of the two largest parties. Faced with this choice, a majority (59%) preferred the one-debate option to the two-debate option—again reflecting, we believe, the public's strong commitment to the wide and equal participation of party leaders noted earlier in the report.

Second, we asked participants to adjudicate the choice of one or two debates in the context of a potential tradeoff between viewership and issue coverage. Here participants were asked to choose between arrangements where: (1) there was only one debate in each language "even though this means less time to cover the issues;" and (2) there was more than one debate in each language "even though this means fewer people may end up watching a debate during the campaign." Faced with these two alternatives, a narrow majority (53%) favoured the multi-debate option. In short, we find that the public's preference for more than one debate is not unconditional—but rather subject to additional considerations, such as what form these additional debates might take.

Lastly, we tackled in greater depth the various types of debates Canadians might want in the federal election campaigns. To be sure, the norm in recent years has been a debate featuring several leaders, covering multiple issues, and including a mix of question sources—but this is not the only way to conduct leaders' debates. In theory, even in a five-week campaign, there is opportunity for a wide range of public events.

To tap the public's preferences for this wider range of event types, including events that are outside the norm of Canadian federal elections, we asked participants to imagine that they were responsible for deciding how many public events should be held in the next election campaign. They were offered the following types:

- Debates between the leaders of all major parties - covering a range of issues

- Debates between the leaders of all major parties - covering the environment only

- Debates between the leaders of all major parties - covering the economy only

- Debates between the leaders of all major parties - covering issues of particular interest to your region

- Debates between the leaders of the two largest parties only - covering a range of issues

- Public meetings where the leaders of all major parties discuss how to work together

- Public meetings between each major party leader and ordinary citizens

- Sit-down interviews between each major party leader and journalists

In addition, participants were provided with a write-in "Other" option.

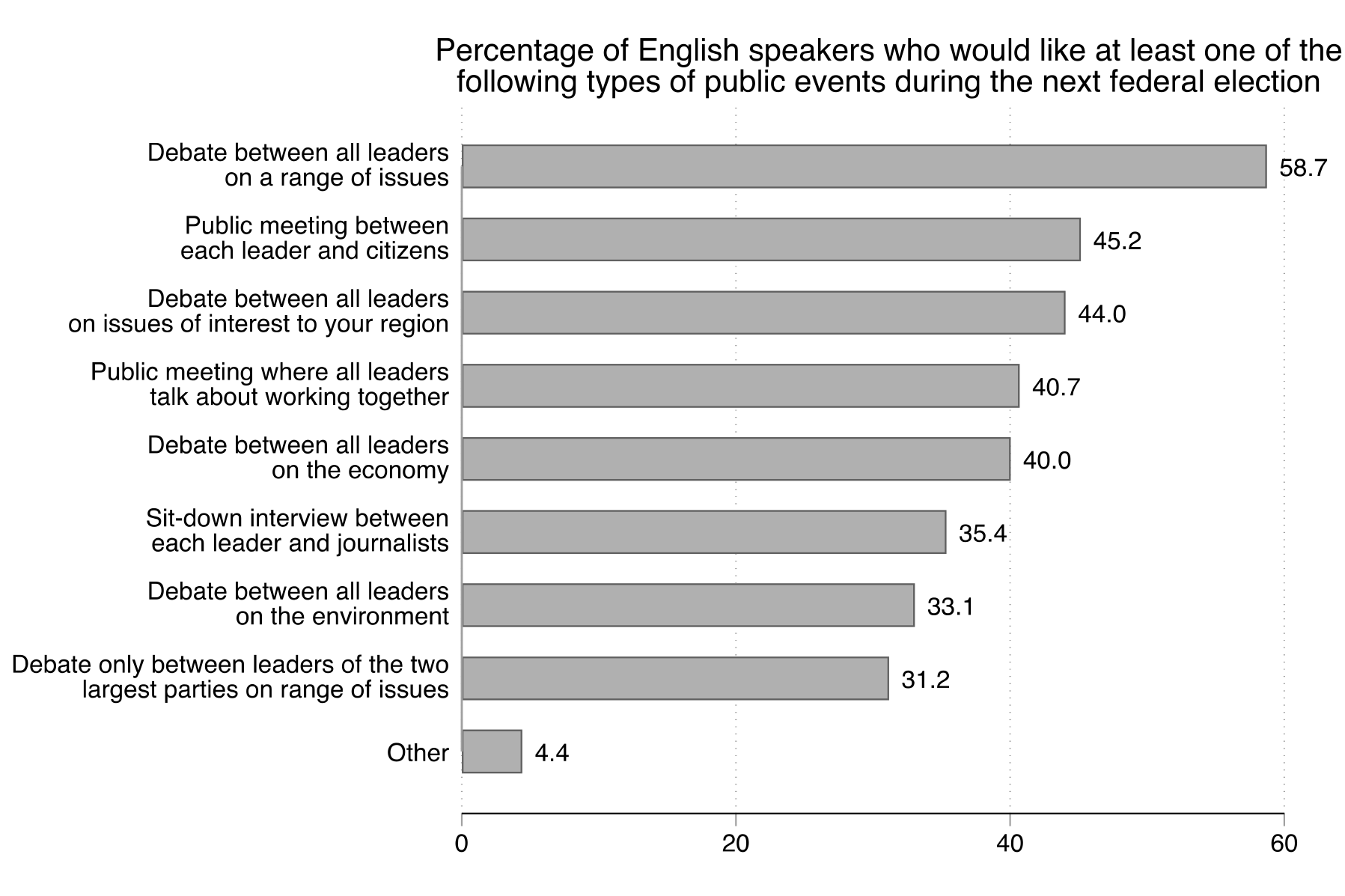

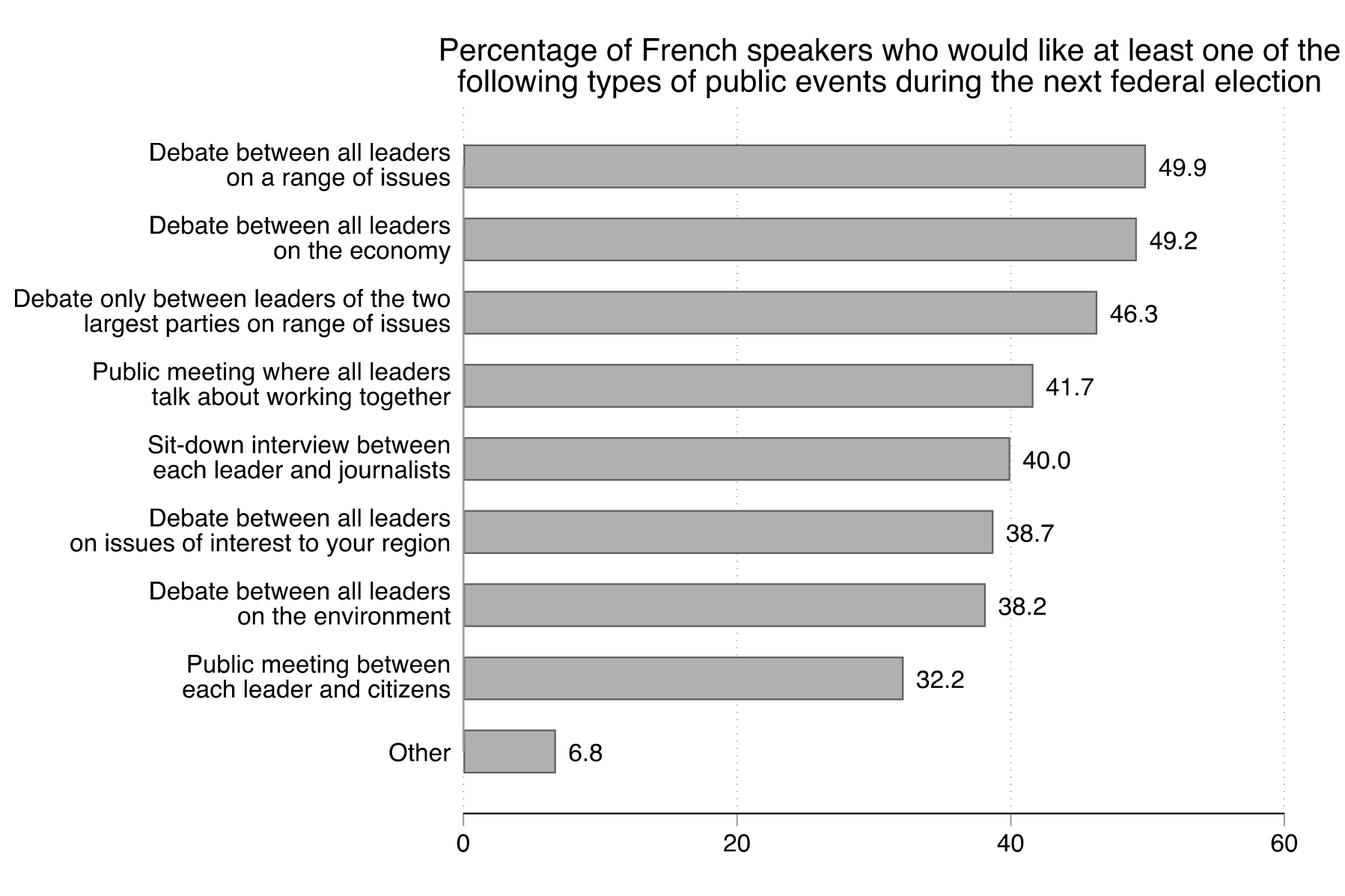

Participants were told that their total selections must be between 1 and 5—meaning they could select five of just one type or distribute their selections across multiple types. The purpose of setting a maximum of five is meant to create a plausible limit on the number of major public events that could reasonably be held during a campaign and, in so doing, incentivize participants to make deliberate allocations in the face of this constraint.