Examination of the Standard for Debate Inclusion

Submitted to

Leaders' Debate Commission

by Nanos Research

January, 2020

Table of Contents

- 1.0 Executive Summary

- 2.0 Background

- 3.0 The Electoral System and Minor Parties

- 4.0 The Decision to Invite the People's Party of Canada in 2019

- 5.0 Lessons from Other Minor Party Insurgencies

- 6.0 Considerations

1.0 Executive Summary

The Leaders' Debates Commission was responsible for organizing and managing the two debates held during the most recent federal election. The following is an examination and analysis of the process for deciding which parties should be invited to participate.

For the 2019 Federal Election, the main question was the appropriateness of inviting a new party such as the People's Party of Canada (PPC) to participate. The Commission decided to invite the PPC because it came to the conclusion that it had a legitimate chance to win seats. The analysis here examines the decision in the context of electoral competition in Canada using results of the 2019 election and previous elections. This examination provides an additional lens to help inform future decisions of the Leaders' Debate Commission.

The report is organized along the following themes:

- The electoral system and minor parties – The rules of the game are critical factors in shaping how new and minor parties

- The first-past-the-post electoral system – Canada's voting system does not favour minor parties. Here we discuss an analysis of the recent historical pattern in relationship to the minimum votes needed to win a riding.

- Movement versus parties formed out of party system failure – Once the nature of converting votes to seats is considered, an examination of the difference between parties formed out of a movement versus those which are most appropriately thought of as those that emerge out of party system failure is explored. That is, when parties fail to adequately represent a key constituency. In Canada, this tends to be regionally based.

- Fixed election dates – Given that the Commission is trying to establish the potential for a party to be successful before the campaign beings, we introduce the idea that the move to fixed election dates will limit overall campaign effects.

- The decision to invite the PPC – After discussing the decision-making process used by the Commission, the report examines the decision compared to the actual election outcome.

- PPC did not convert votes to seats – An analysis of the geographic distribution of support for the Party shows a clear lack of geographic base.

- An analysis of riding surveys conducted in four ridings believed to be likely to elect a PPC candidate – The Commission administered a test based on the percent of each riding willing to consider voting for the PPC candidate. In light of the nature of the electoral system a post election outcome review suggests that standard was too easy to achieve and overestimated the chance of the Party electing multiple candidates.

- Lessons from other minor party insurgencies – The Green Party, the Bloc Québécois (BQ) and the Reform Party experience help inform our understanding of the possibility of the PPC winning seats.

- Green Party – Lacking a regional base, the Party failed to win seats in many elections because vote shares below five percent nationally are unlikely to generate seats. The party was more successful in later elections when it had regional strength of 10 percent or more.

- Bloc Québécois – A classic example of party-system failure, the BQ experience highlights the impact of a regional base. Even before the campaign began, it's potential to win seats was evident given its strong voter support in Quebec.

- Reform Party – Like the BQ, the Reform Party was clearly poised to win seats and had a strong regional base. Finally, it took the Reform Party two elections to establish a base. It did not easily convert electoral presence to seats.

The analysis of the People's Party experience in light of our democratic the system and the experience of other parties leads to two elements that the Commission can consider in assessing the process for including minor parties in future debates.

- Regional strength matters. Adding a regional popular support criterion (e.g. 10% minimum vote share) to evaluate admission to the Leaders' Debate would help better capture the dynamics of minor parties in Canada. Minor parties without a regional base have a very low likelihood of converting votes to seats.

- A stronger minimum support level should be considered. The Commission may want to continue in some circumstances using a "willingness to consider the party" test to evaluate the legitimate chances of winning a seat. Since few candidates win with between 25 and 30 percent of the vote, a standard of 40 percent willing to consider is probably more likely to be a robust indicator of electoral success.

The 2019 federal election represented a positive first step for the Leaders' Debate Commission at it deliberated on how to best operationalize the parameters for including in the Leaders' Debate. The analysis by Nanos suggests that, taking the learnings from the 2019 federal election the parameters for inclusion can be better refined. To follow is a more detailed examination of the items articulated in the Executive Summary.

2.0 Background

The Leaders' Debates Commission is interesting reviewing the process it used for considering which parties should be invited to participate in debates. In the lead up to the debates for the 2019 Federal Election, the main question was the appropriateness of inviting a new party such as the People's Party of Canada (PPC). Although initially not invited, the Commission ultimately decided to invite the PPC. This memo reviews the process used to invite this new party, considers the true performance of the parties, and reviews the historical record of minor parties to offer a set of observations for the Commission to consider in formulating future decisions. For the purposes of this discussion a minor party is a party without a significant number of seats in the House of Commons.

The inclusion of the People's Party in the debate is not an experiment. Including the party could have had an impact on the result. Participation in the debates could have either helped or dampened its electoral prospects. Inclusion may have legitimized the party as a serious party with a chance of winning. Exposure may have also increased awareness of its platform. It may, however, have exposed the public to its platform or to its leader's competence and character that reduced the likelihood of support. The one known in the process is that the electoral prospects of the PPC did not increase with participation in the Leaders' Debates.

One should exercise caution in simply concluding that the lack of seats won is an indicator that the Party should not have been invited. One can, however, use the PPC experience in 2019 along with the experience of other minor parties to evaluate the claim that the party had a legitimate chance to win seats (more than one).

3.0 The Electoral System and Minor Parties

I. Minimum votes to win a riding

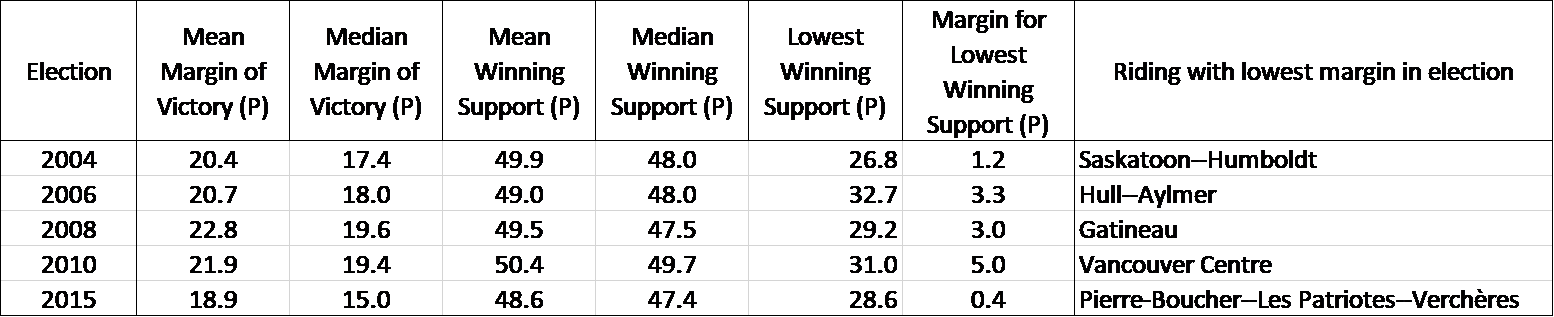

Canada's first-past-the-post system does not favour minor parties. The winner-take-all proposition in each riding means that candidates can be elected without getting a majority in the riding. When we examined riding outcomes for the 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010 and 2015 federal elections in Canada, there were several key stats that highlight the difficulty in converting votes into seats.

A review of the five elections leads to a number of key observations:

- Margin of Victory - The average margin of victory for the most recent elections examined was between 18.9 and 22.8 per cent while the median margin of victory ranged between 15.0 and 19.6 per cent.

- Winning Support – The average percentage level of support of the winning candidates was between 48.6 and 50.4 per cent while the median winning support in ridings was between 47.4 and 49.7 per cent.

- Minimum Required to Win – The lowest percentage required to win at the riding level in the most recent elections ranged between 26.8 and 32.7 per cent.

All things being equal, an 'average' party expecting an 'average' winning level of support would need support of about 45 per cent to win in a single riding. The lowest possible level of support is 26.8 per cent, which was achieved in 2004 in the Saskatoon-Humboldt riding. Of course, winning with such a low level of support requires three other competitive parties to split the other 73 per cent of the vote.

II. Party system failure versus movement parties

For the purposes of this memo it is useful to consider two types of minor parties. The first, are those who emerge out of party system failure. One or all of the major parties fail to adequately represent a large proportion of Canadians usually with decidedly regional grievances. This is not to say that these parties are not fuelled by and passionate about ideas. The key is that the broad consensus that underlies the party breaks down. Parties fracture.

The second is parties that emerge as a movement. Here ideas matter more than electoral success. The Green Party would fit this mold as would many of the plethora of minor parties that offer candidates for office with little expectation of electoral success.

The PPC arguably is closer to this conception of a minor party than a party emerging out of party system failure. The party focuses on unique issues. For this reason, it is worth considering how parties as movement have electoral success in a system that punishes parties for not having concentrated votes.

III. Fixed election dates and campaign effects

One of the additional considerations is the fact that we have fixed electoral dates. While it is possible to have an early election, the expectation that the election will be occur regularly every four years on a specific day means that the campaign is effectively much longer than the actual writ period. One can reasonably expect that the impact of the formal campaign is smaller when the election day is already decided months in advance of the dropping of the writ. Only something that fundamentally changes what voters know or are thinking about could dramatically change the fortunes of a small party. Much of the likely success of a small party is embedded in the pre-writ survey results.

4.0 The Decision to Invite the People's Party of Canada in 2019

I. How the Commission Decided

In coming to its decision to invite the parties to participate in the debates the Leaders' Debates Commission requirements to be met are provided below.

As outlined in section 2(b) of the OIC, invitations to participate in the leaders' debates are to be extended to "the leader of each political party that meets two of the following criteria":

- at the time the general election is called, the party is represented in the House of Commons by a Member of Parliament who was elected as a member of that party,

- the Debates Commissioner considers that the party intends to endorse candidates in at least 90% of electoral districts in the general election in question,

- (a) the party's candidates for the most recent general election received at that election at least 4% of the number of valid votes cast or, (b) based on the recent political context, public opinion polls and previous general election results, the Debates Commissioner considers that candidates endorsed by the party have a legitimate chance to be elected in the general election in question.[Note: (a) and (b) added by Nanos]

On the basis of these criteria six parties were invited to attend. The PPC was originally not invited but after receiving additional information did extend an invitation. The table below also shows the number of seats won and the criteria that was used to determine participation.

| Party | Qualification Criteria | Seats won in the 2019 election |

|---|---|---|

| Bloc Québécois | i. (Sitting members in House); ii. More than 4% of vote in previous election | 32 |

| Conservative Party of Canada | i. (Sitting members in House); ii. More than 4% of vote in previous election | 121 |

| Green Party of Canada | i. (Sitting members in House); ii. Offering candidates in at least 90% of ridings | 3 |

| Liberal Party of Canada | i. (Sitting members in House); ii. More than 4% of vote in previous election | 157 |

| New Democratic Party | i. (Sitting members in House); ii. More than 4% of vote in previous election | 24 |

| People's Party of Canada | ii. Offering candidates in at least 90% of ridings; iii. More than 1 candidate has a chance of being elected | 0 |

NOTE: One seat was won by an Independent candidate in the 2019 election.

The People's Party was the party that the Commission had to evaluate closely given that it had no previous electoral success that would allow it to be qualified under i. or iii.(a). Because the leader was elected as a Conservative and the party had not run candidates in previous elections, there was no basis for including the party unless it met criteria ii. (fielding a full slate of candidates >90%) and iii(b) (having a legitimate chance of being elected. The Commission determined that a legitimate chance of being elected in more than 1 riding was the minimum condition.

The key wording in iii(b) is the words, recent political context. The Commission in their words used the following to determine the political context:

- Evidence provided by the party in question in relation to the criterion;

- Both current standing and trends in national public opinion polls;

- Riding level polls, both publicly-available and internal party polls if provided as evidence by the party and riding projections;

- Information received from experts and political organizations regarding information about particular ridings;

- Parties and candidates' performances in previous elections;

- Media presence and visibility of the party and/or its leader nation-wide;

- Whether a party is responsive to or represents a contemporary political trend or movement;

- Federal by-election results that took place since the last general election;

- Party membership; and

- Party fundraising.Endnote i

On the basis of publicly available polling in Beauce, riding polls conducted in four potentially contending ridings by the Commission, and information about fund-raising, party membership and media presence, the decision was made to invite the party.

II. PPC support (national and regional)

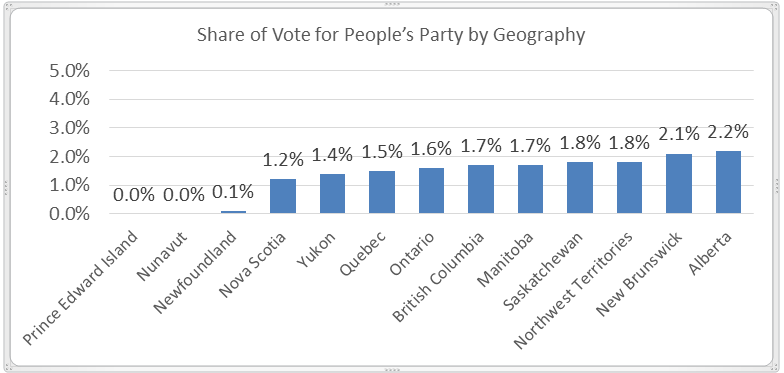

Overall, the People's Party received 1.6% of votes cast and no seats. This is lower than the national poll averages throughout the election, which generally ranged from 2-4 percent. National vote shares are, however, not necessarily indicative of riding success, especially for regionally oriented parties. Regional or local strength can convert to seats.

The People's Party of Canada, however, had no meaningful regional or provincial support. Below is the share of the vote in the election by province/territory. The final vote shares mirror the national polls at the beginning of the campaign. The PPC did not have a regional strength, which significantly reduced the likelihood of winning seats.

III. Analysis of how PPC did in the five ridings the Commission analyzed

One of the ways the Commission assessed the electoral viability of the People's Party was to review publicly released polling for the Beauce riding. These polling suggested that the PPC was viable in Beauce.

To establish whether it had a chance to win elsewhere riding pollsEndnote ii were commissioned to establish the willingness to consider voting for the PPC in four ridings the PPC felt it was most competitive. In each riding, respondents were asked "How likely are you to vote for_______, the People's Party of Canada candidate in your riding in the next federal election?".

The willingness to consider the party, as was argued elsewhere, has the advantage of assessing the potential support for the party without explicitly asking the vote intention question. Potential support is independent of any strategic considerations that voters might use in forming their final vote decision. If 40 percent of voters in a riding would consider voting for a candidate, that would represent the maximum vote share for that party. To get 40 percent, ever person would need to act on their consideration. Of course, people are free to consider more than one party.

It is unrealistic to assume that every single person who is considering a party would actually vote for that party. So a party's ultimate vote will be based on what percentage of the electorate can be motivated to act on their openness to consider a party plus any change in the willingness to consider the party between the polling and the actual vote.

The Commission determined that since the Party had more than 25% of the electorate in the riding willing to consider it, that the PPC was a legitimate contender to win multiple seats.

As noted earlier, a 25 percent threshold is the minimum amount of local voter support that has produced a winning seat among the most recent federal elections. In order for the PPC to reach that minimum share of votes (25%), virtually everyone who indicated that they would consider the party would have to actually cast a vote for that party. This represented a minimum standard for the PPC to meet. This 25 per cent threshold also requires a number of competing parties which would effectively split the vote in a first-past-the-post system.

The table below shows the percentage who would consider voting for the party and the ultimate vote share for the party in each riding. Two things are of note:

- Actual vote shares did not come close to making the districts competitive. Only in Nipissing-Timiskaming did the PPC party receive more than 5% of the votes. In the end, less than half of those who expressed a certainty to vote for the PPC candidate could have done so to reach their level of electoral support.

- The Commission used a generous interpretation of willingness to consider. The question was asked on a 4-point scale and the Commission reached the 25 percent threshold by adding together the percentage who provided a certain to vote, likely to vote, and possibly will vote. Given that the probability of actually voting for the party increases with the strength of one's conviction, aggregating all three response categories allowed for a higher legitimacy of the PPC's being competitive. For example, for the PPC to reach 26 percent support in Pickering-Uxbridge, the party would need the 9.3 percent who only felt a vote for the PPC candidate was a possibility to cast their vote this way.

- Getting to the 25 percent threshold did not provide much chance of electoral success. Even if the party received 25 percent of the vote (which the consideration data indicated was unlikely), its chance of electoral success was mathematically still remote. Only one candidate between 2004 and 2015 was elected with 27% of the vote.

On election day, the People's Party was only competitive (finishing 2nd) in one riding (Beauce). In fact, its presence in all these ridings did not even impact who won as the winning candidate in each riding won by more than the PPC vote share.

| Nipissing-Timiskaming | Etobicoke North | Pickering-Uxbridge | Charleswood-St.-James-Assiniboia-Headingley | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certain to vote for that candidate | 11.2% | 15.3% | 11.2% | 10.6% |

| Likely to vote for that candidate | 6.1% | 5.2% | 5.4% | 4.4% |

| Possibly will vote for that candidate | 16.9% | 9.4% | 9.3% | 9.5% |

| Will not vote for that candidate | 59.0% | 62.2% | 67.9% | 73.2% |

| No answer | 6.9% | 7.9% | 6.2% | 2.3% |

| Net: Top 3 | 23.0% | 29.9% | 25.9% | 24.5% |

| Net: Top 2 | 17.3% | 20.5% | 16.6% | 15.0% |

| Actual vote share | 5.2% | 2.8% | 2.0% | 4.3% |

5.0 Lessons from Other Minor Party Insurgencies

I. Green Party

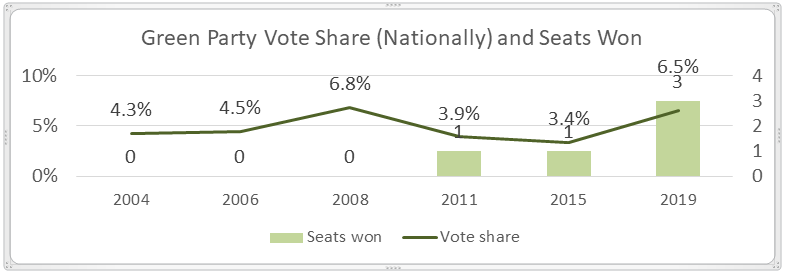

A useful perspective on the process and the challenges a small party faces having electoral success is the Green Party. It has now won seats in three general elections plus some by-election wins but it had strong showings in the previous elections with no seat success.

The challenge of new parties converting votes to seats is not a minor one. In 2008, the Green Party won 6.5 percent of the vote nationally but received no seats for their effort. The same vote in 2019 led to 3 seats. For three elections, between 2004 and 2008, the party was able to surpass the four percent of the national vote but was unable to win any seats.

A look at the regional distribution helps account for the inability for the party to convert votes to seats. In 2004, provincial vote shares varied between two and six percent. By 2019, the Green Party had achieved double digit vote shares in six provinces or territories. Reaching double digits did not guarantee seats in that region but it made it more probable. In B.C., eight percent of the vote elected one candidate in 2011 and one in 2015 but nine percent in 2008 did not lead to electoral success.

Movement parties like the Green Party face significant challenges. Without a strong regional base, there is no guarantee that votes will turn into seats. And, in the absence of major party failure that frees voters to move to other parties, the minor party trajectory for improvement is uneven. Gradually over a course of many elections, there is the possibility of increased electoral success but it is always tenuous.

| N.L. | P.E.I. | N.S. | N.B. | Que. | Ont. | Man. | Sask. | Alta. | B.C. | Y.T. | N.W.T. | Nun. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 3% | 21% | 11% | 17% | 4% | 6% | 5% | 3% | 3% | 12% | 10% | 11% | 2% | 7% |

| 2015 | 1% | 6% | 3% | 5% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 8% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 3% |

| 2011 | 1% | 2% | 4% | 3% | 2% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 5% | 8% | 19% | 3% | 2% | 4% |

| 2008 | 2% | 5% | 8% | 6% | 3% | 8% | 7% | 6% | 9% | 9% | 13% | 5% | 8% | 7% |

| 2006 | 1% | 4% | 3% | 2% | 4% | 5% | 4% | 3% | 7% | 5% | 4% | 2% | 6% | 4% |

| 2004 | 2% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 6% | 6% | 5% | 4% | 3% | 4% |

* highlighted cells indicate where party won seats

As an experiment, it is interesting to look back at the criteria for inclusion as they apply to previous elections. In 2019, the Green Party qualified under i. (member of the House of Commons) and ii. (offing candidates in 90% or more of riding). It did not, however, meet the threshold of four percent support in the previous election. In fact, electing someone in the previous general election would have been critical to getting an invite in 2019 and 2015. In earlier elections as long as the party offered enough candidates, it would have been invited to the debate even though it had little chance of electoral success.

The Green Party experience provides several insights into the process by which a minor party converts votes to seats. First, vote shares below five percent nationally are unlikely to generate seats. It is possible for an established leader/ politician to win a seat when their party is at five percent or below but this requires a unique person. Second, regional strength of 10 percent or more is the best indicator of potential seats.

II. Bloc Québécois (BQ)

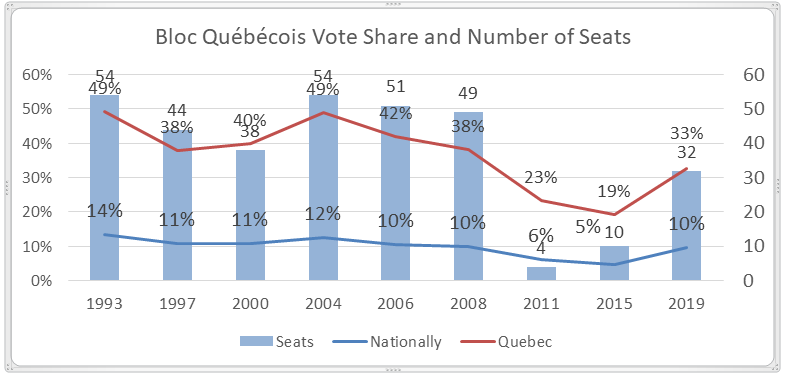

The Bloc Québécois represents a classic case of a regionally-based disruption to the party system. Since it never offers candidates outside of Quebec, it's national vote total is not particularly relevant except as to understand how a low national vote can sometimes translate into seats.

National vote shares for the BQ have fluctuated from a low of five to a high of 14 percent. Even at five percent, the party was able to win 10 seats. But winning seats was a result of receiving 19 percent of the vote in the region. But the shift between 2008 and 2011 highlights a key aspect of the way votes get converted into seats. Between 2008 and 2011, the share of the vote in Quebec dropped from 38 to 23 percent (15 points or 39%) but seats dropped from 49 to four (a decline of 92%). Once even regional vote shares drop below 25 percent, success in terms of seats is not guaranteed.

Technically the party did not win seats until 1993 but Gilles Duceppe, was elected in a by-election in 1990, a year before the party was legally formed. As such, the party which would go on to win 54 seats would not have qualified under the Commission's rules for debate inclusion as it had no elected candidates, did not field candidates nationally, and had not received four percent of the vote (iii.a). Of course, it would have been considered likely to win seats under iii.b.

Significant political support was already evident in the Spring of 1993. An Environics surveyEndnote iii found that among decided voters found the B.Q. at 12.5% nationally and 47% in Quebec.

The Bloc Québécois experience highlights the importance of regional/ provincial support. It also is important in showing the dynamic by which traditional parties get usurped by a new party. Finally and importantly, the seeds of the BQ success were evident well before the campaign started.

III. Reform

The BQ represents the most regionally concentrated version of a new party that emerged out of party system failure. The Reform Party is a further example of a party that started with a regional foothold. Formed in 1987, the part contested the 1988 election but did not elect any Members of Parliament.

- In 1988, the early signs of potential regional impact were evident. Although it did not win any seats and was not a national party, it won 15.4 percent of the vote in Alberta and 4.8 percent in B.C.

- In June of 1993 an Environics survey found that among decided voters 7.4 percent would vote for the Reform Party if the election was held today. Months before the election, the Reform Party also had a regional presence with significant support in Manitoba/Saskatchewan (15%), Alberta (19%) and British Columbia (19%).Endnote iv

- The 1993 election catapulted the party to 52 seats. Again, the regional strength was obvious. The Party won 52 percent of the vote in Alberta.

There are several lessons we can take from the Reform experience. First, while few would have predicted the size of the electoral success in 1993, the Party was clearly poised to win seats. Second, its electoral legitimacy was driven by its strong regional base. Campaign dynamics shaped the final tally, but they were clearly competitive regionally before the campaign started. Third, it took the Reform Party two elections to establish a base big enough to legitimately compete for seats. Getting to 15 percent of the vote in 1988 did not lead to any seats but it set the foundation for later success.

| N.L. | P.E.I. | N.S. | N.B. | Que. | Ont. | Man. | Sask. | Alta. | B.C. | Y.T. | N.W.T. | Nun. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | 3.3% | 15% | 5% | 2.1% | ||||||||||

| 1993 | 0% | 1% | 13% | 8% | 0% | 20% | 22% | 27% | 52% | 36% | 13% | 8% | 18.8% | |

| 1997 | 3% | 2% | 10% | 13% | 0% | 19% | 24% | 36% | 55% | 43% | 25% | 12% | 0% | 19.4% |

6.0 Considerations

Decisions about who to invite to participate in debates are important for the health of our democracy. While we do not make specific recommendations, the analysis here suggests the following key points for the Commission to consider going forward.

- Regional strength matters. The current criteria for inclusion do not specifically address the situation where a party is strong regionally but weak nationally. There is room to add a regional popular support lens to evaluate admission to the Leaders' Debate. The BQ would not have been invited to participate in a debate in 1993 based on the current decision-making due to the fact that they had no previous electoral experience and was not contesting 90 percent or more of the ridings in Canada. Regional strength also matters because minor parties without a regional base have a very low likelihood of converting votes to seats. A requirement for a minimum vote share (e.g. 10%) in a province might be a useful indicator of whether a seat could be won there.

- A stronger minimum support level should be considered. Recognizing that even provincial aggregation may not fully capture significant local support, the Commission may want to continue in some circumstances using a "willingness to consider the party" test to evaluate the legitimate chances of winning a seat. The standard used in 2019, however, was a lowest bar based on recent historical data. Few candidates win with between 25 and 30 percent of the vote. A standard of 40 percent willing to consider is probably more likely to be a more robust indicator of electoral success as opposed to the minimum possible. The experience of other minor parties without a strong regional base, such as the Green Party, is that winning more than one seat is highly unlikely with less than 10 percent of the national vote.