Democracy matters: Making debates count for citizens

A report on the Leaders' Debates Commission 2021 federal election experience

On this page

- Message from the Debates Commissioner: On democracy, trust and leaders' debates

- Section 1 - Implementing the Commission's mandate

- Section 2 – Principal findings

- Section 3 – Beyond 2021

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Appendix 1 – Leaders' Debates Commission – Orders in Council

- Appendix 2 – Leaders' Debates Commission – Advisory Board terms of reference

- Appendix 3 – Stakeholders Consulted

- Appendix 4 – Media Coverage

- Appendix 5 – Participation criteria for the Leaders' Debates

- Appendix 6 – International lessons learned

- Appendix 7 – Workshop on Debates Production

- Appendix 8 – Workshop on Participation Criteria

- Appendix 9 – Workshop on the Future of Debates in Canada

- Appendix 10 – Canadian Election Study – Evaluation of the 2021 leaders' debates

- Appendix 11 – Accessibility and Distribution

Message from the Debates Commissioner: On democracy, trust and leaders' debates

Canada has a strong history of democratic government and respect for civil liberties. But we live at a time when democracy is in decline around the world. Based on a five-part rating system, the 2021 Economist Democracy Index concludes that only 6.4% of the world's population lives in a full democracy, with only 21 countries, including Canada, ranking as full democracies. The 2021 Freedom House Freedom in the World Index reports a 15th consecutive year of decline in global freedom and that "democracy is under siege."Footnote 1

Canada's democracy has done relatively well so far, but one of our greatest dangers is complacency, which is why informed elections that engage our citizens are more important than ever. It is here that leaders' debates can make an important contribution: we know that seeing leaders together, live on stage, answering tough questions and challenging each other's ideas and opinions, helps Canadians learn about political leadership and issues that matter. And at their best, debates can reflect our core values such as fairness, civility and pluralism.

Debates are more than campaign events or journalistic exercises. The 2021 Canadian Election Study (CES) showed that the 2021 leaders' debates increased trust in government, the media and political parties.Footnote 2 In an age of disinformation, fragmentation of audiences and polarisation of public opinion, leaders' debates produce an authentic record of party positions that citizens can trust and come back to repeatedly. Done well, leaders' debates are a public trust, that in turn, can help build trust.

Making debates count

The Leaders' Debates Commission (LDC) has now gained the lessons of two election cycles. From high levels of debate viewership and public discourse, we have learned that debates can potentially serve as a focal point for an election campaign. We have made some good progress on making the debates accessible, recognizing that reaching out to remote and marginalized communities is vitally important. We are also learning, through trial and error, about what can make for compelling, predictable and informative future debates. Debates are iterative exercises that require constant evaluation and improvement. Our report makes a number of practical suggestions on how to strengthen debates. We hope it can provide a useful guide for future debate authorities. With constant learning and subject to regular review, we believe leaders' debates can be a model for effective debates at all levels across the country and help set national standards of civil discourse.

The LDC team is particularly grateful to the many individuals and institutions who have helped us so far. They have shared invaluable experience gained over many years in Canada and abroad. Their research underpins many of our findings. Their thoughtful advice has helped to shape many of our recommendations. Together, they are helping to make our future debates a better and more permanent part of our democratic system. In so doing, they are helping to gather a diversity of voices around debates and elections, and building an ongoing community rooted in Canada but global in scope.

It has been an honour to work with a dedicated team to help nurture a renewed interest in our democratic institutions through leaders' debates. This team, largely part-time, led by Michel Cormier and composed of Bradley Eddison, Jess Milton, Chantal Ouimet, Kelly-Ann Benoit, and Stephen Wallace (who served pro bono), is as professional and committed to the public good as any I have ever encountered.

We have a strong foundation in Canada to reinforce our democracy. But the endurance of democracy demands both constant vigilance and collective vigour. In the same way, building trust in our institutions requires constant attention and commitment. We are conscious of the public trust we hold to ensure effective and informative debates that establish worthy standards of civility, truth and transparency. The report that follows set outs what we have accomplished, what we have learned, and what can be built for the future.

David Johnston

Debates Commissioner

Section 1 - Implementing the Commission's mandate

The September 2021 federal election was the second political cycle in which the LDC organized debates. As in 2019, the Commission was mandated to organize two debates, one in each official language.

This report analyzes to what extent the LDC delivered on its mandate in 2021.

After the most recent experience, which drew significant stakeholder criticism, the Commission must carefully assess what it has accomplished and whether its continued existence is necessary. In other words, does the LDC add anything worthwhile to the debate ecosystem that would not be generated otherwise? If so, should the mandate, role and structure of the Commission evolve to ensure improvements in the organization and delivery of the debates?

We believe that a candid self-assessment of the 2021 experience is key to identifying what works and what needs to be improved.

The context

Before analyzing the 2021 experience, it is useful to recall the context that led to the creation of the LDC in 2018. The decision to establish the Commission stemmed from the 2015 federal election campaign experience, which failed to produce a widely viewed and distributed English-language debate.

By mandating an independent Commission to organize two leaders' debates, one in each official language, the Government indicated it wanted to reduce the possibility that negotiations between the political parties and television networks would fail to produce debates, or would produce debates with limited public reach. It also wanted to bring more predictability, reliability and stability to the debates.Footnote 3

Article 4 of its 2018 Order in Council (OIC) defines the Commission's role in the following terms: "In fulfilling its mandate, the Leaders' Debates Commission is to be guided by the pursuit of the public interest and by the principles of independence, impartiality, credibility, democratic citizenship, civic education, inclusion and cost-effectiveness."Footnote 4

The 2019 experience

The Commission's work is iterative. To find the best way forward, it is necessary to consider the road travelled. The 2019 debates, post-debate consultations and our 2019 report all informed the approach we took in organizing the 2021 debates.Footnote 5

The 2019 experience provided stability to the debates. The participation rules were made public and political parties committed well in advance to take part. The debates also increased their reach and viewership. Debates were made available in a range of languages other than French and English, including Indigenous languages, American Sign Language (ASL) and Langue des signes québécoise (LSQ). Public opinion surveys conducted for the Commission revealed that a majority of voters believed the debates helped them make their choice in the election.Footnote 6 As we concluded in our 2019 report: democracy matters, debates count.

There were, however, areas for improvement. Our 2019 report contained 11 recommendations. The principal recommendation, based on a wide consensus stemming from consultations, was that the LDC be made permanent, provided that measures are maintained to ensure its independence, impartiality and transparency. The Commission also recommended that it ultimately be established through legislation, that its Commissioner be appointed in consultation with political parties represented in the House of Commons, and that the Commission maintain some operational capacity between elections. The LDC would use that time to maintain relationships with stakeholders and foster discussion about best debate practices in format and production.

The Commission also recommended that the Commissioner, not the Government, set the participation criteria and that these should be as clear and objective as possible and be made public before the election campaign.

Finally, the Commission recommended that it should reserve the right of final approval of the format and the production of the debates, while respecting journalistic independence.

Renewed 2021 mandate

The Commission's term ended on March 31, 2020, shortly after it submitted its report and financial statements. In November 2020, the Government reappointed a Debates Commissioner and issued an OIC to provide the LDC with an amended mandate to organize two debates, one in each official language, for the minority government political cycle.Footnote 7

This amended OIC included three additional elements of the LDC's mandate:

- Set participation criteria and make them public;

- Ensure the debates are available in languages other than French and English, paying special attention to Canada's Indigenous languages; and

- Provide final approval of the format and production of the leaders' debates, while respecting journalistic independence.

The Government thus gave the LDC the authority to deal with two major issues stemming from the 2019 debates: setting clearer, more objective participation criteria and final approval of the debates' format.

The next section looks in more detail at the Commission's 2021 mandate and examines to what extent it delivered on it. This assessment will form the basis for our 2021 recommendations.

Section 2 – Principal findings

As noted above, the LDC's OIC provided several objectives.

To review whether the Commission achieved these objectives, we examined the 2021 leaders' debates and consulted widely with stakeholders both here in Canada and internationally. We held four debate symposia with experts in debate production, organization and polling. We spoke with debate moderators, producers and television executives around the world. We interviewed more than 40 stakeholders from the Canadian experience on everything from how to choose a moderator, to how to improve on interpretation. We asked for feedback from the public and received more than 1,100 submissions from Canadians. We worked with the Canadian Election Study (CES) at the University of Toronto to survey 2,000 Canadians on what makes successful debates.

This section seeks to provide a factual analysis of our 2021 experience.

2.1 Were the debates accessible and widely distributed?

The English-language and French-language debates were available live on 36 television networks, four radio networks, and more than 115 digital streams. Canadians were also able to watch the debates online after they aired in the language of their choice.Footnote 8 The debates were provided in 16 languages, including six Indigenous languages and ASL and LSQ. They were also available in closed captioning and described video. Fewer than 5% of non-viewers indicated that their main reason for not watching the debates was a lack of accessibility.Footnote 9

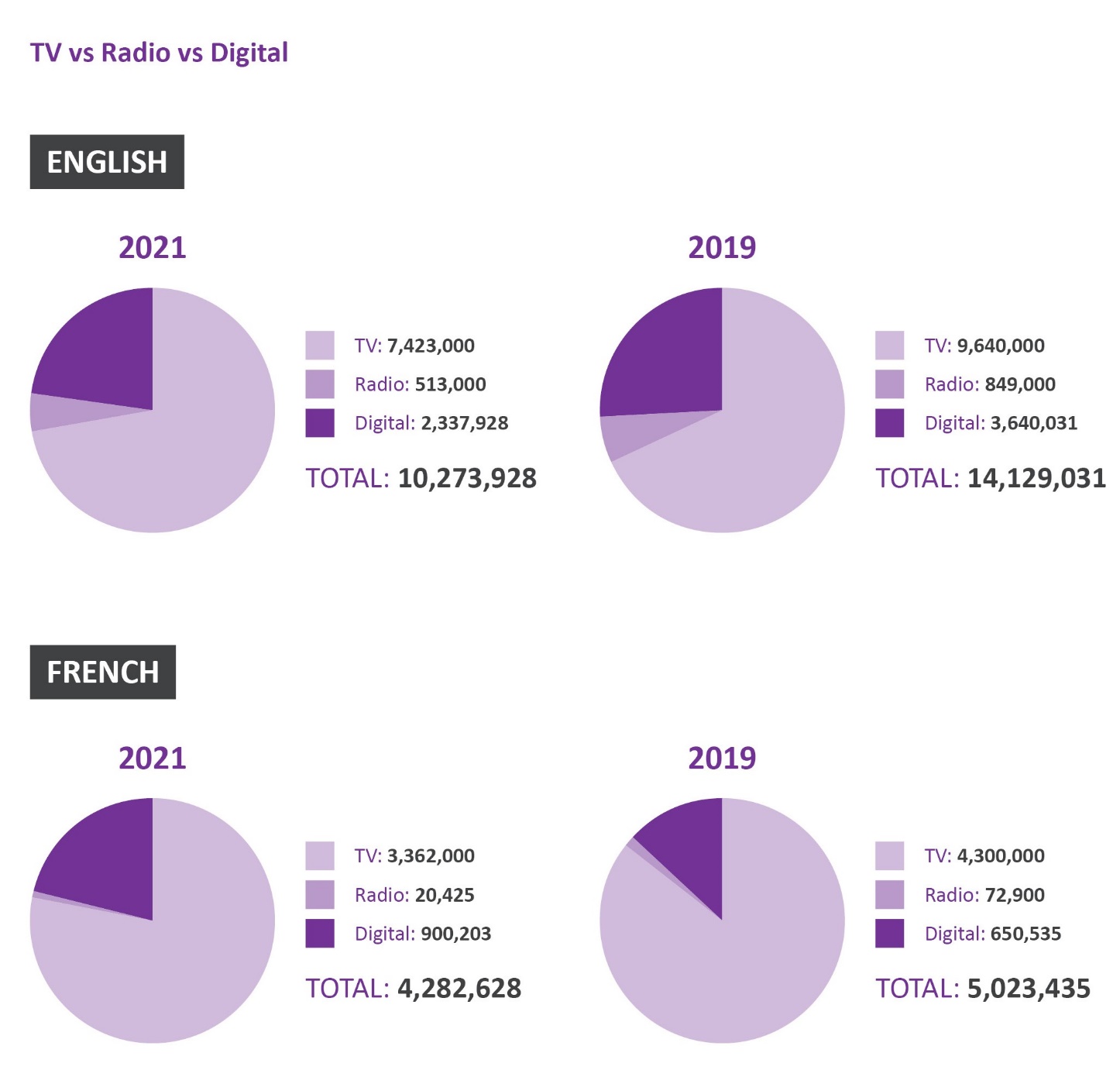

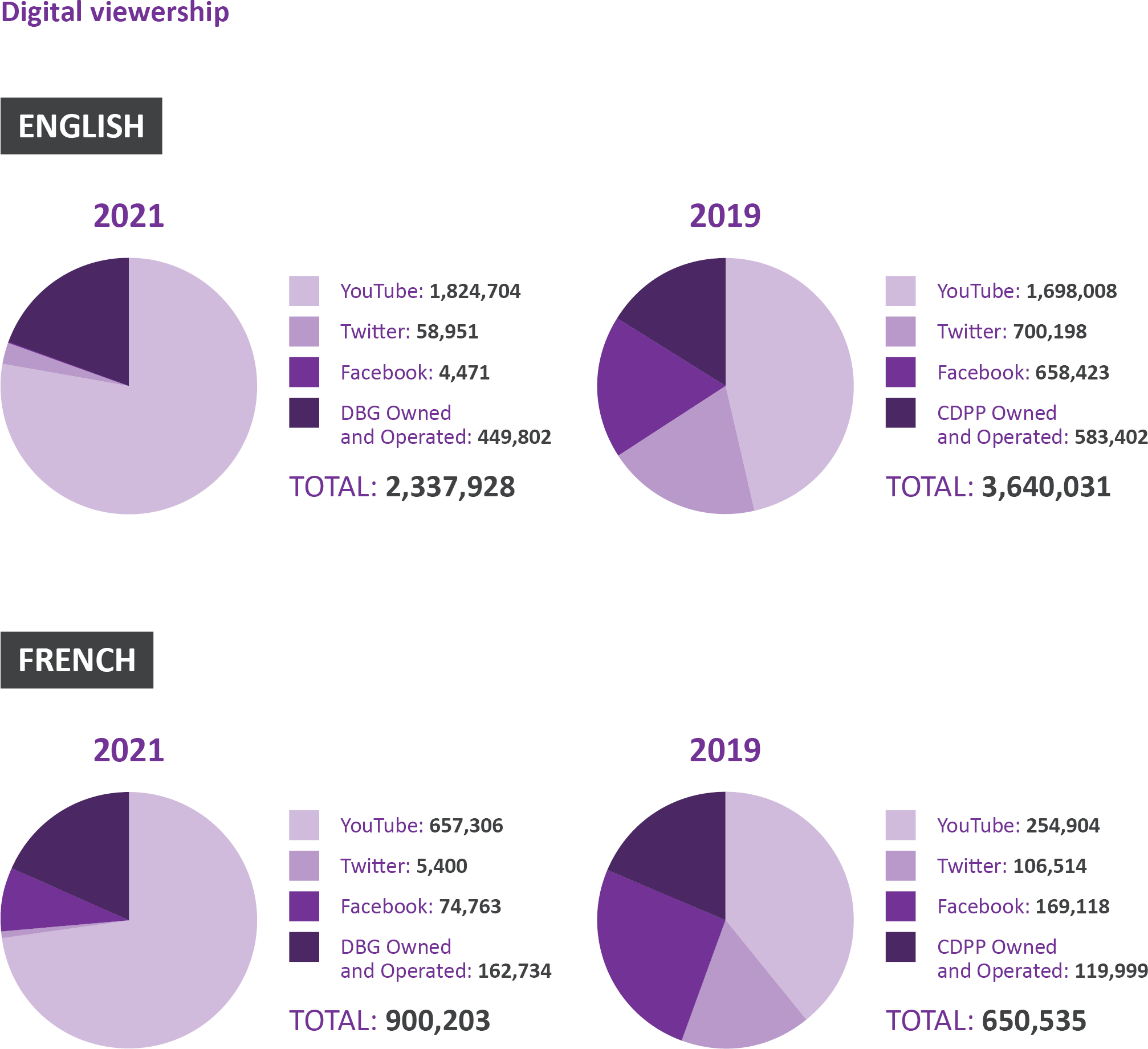

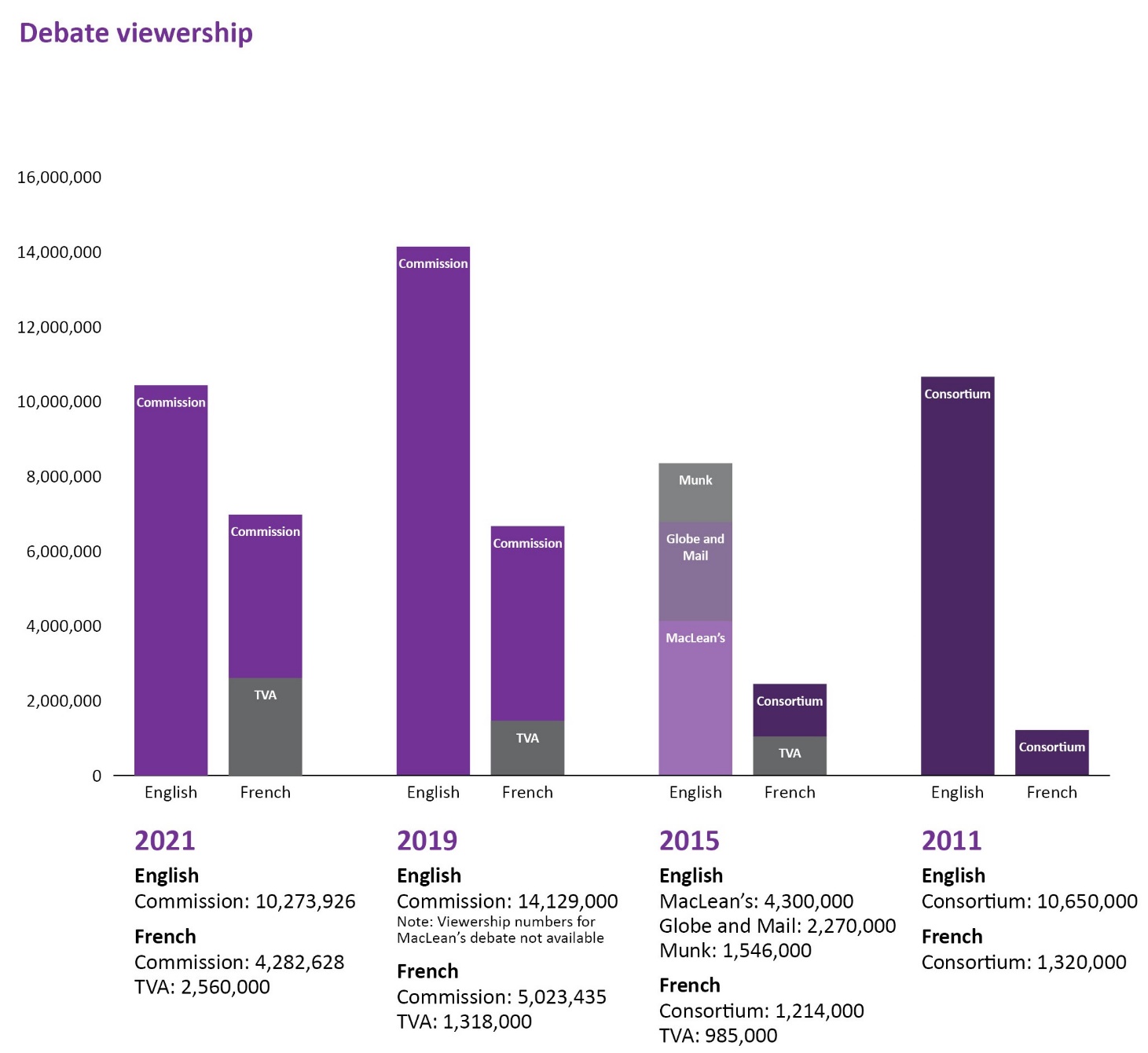

More than 10 million Canadians tuned in to the English-language debate and over four million watched the French-language debate. These numbers are large in comparison to both international debate ratings and Canadian television programming. For instance, in 2021, 8.8 million Canadians watched the Super Bowl.

| 2011 | 2015 | 2019 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Consortium: 10,650,000 | MacLean's: 4,300,000 Globe and Mail: 2,270,000 Munk: 1,546,000 |

Commission: 14,219,000 MacLean's: ratings N/A |

Commission: 10,273,926 |

| French | Consortium: 1,320,000 | Consortium: 1,214,000 TVA: 985,000 |

Commission: 5,023,435 TVA: 1,318,000 |

Commission: 4,282,628 TVA: 2,560,000 |

| TOTAL | 11,970,000 | 10,315,000 | 20,560,435 | 17,116,554 |

2.2 Were debate invitations issued on the basis of clear, open, and transparent participation criteria?

In 2021, the LDC set participation criteria and made them public in advance of the election. The Commission also made public its rationale for how it would apply the criteria, as well as its decision on which party leaders met the criteria to be invited. Invitations to party leaders were subsequently made public, as were the leaders' responses.

Stakeholders generally thought the Commission developed sound criteria and applied them clearly and objectively. There was some feedback that the application date of these criteria should aim to be as close to the debates as possible and should use data that was as recent as possible. That said, the debates producer pointed out that a "late hour" determination of the number of leaders on stage could jeopardize their ability to produce a debate of high quality, as required by the OIC. It could also impact the ability of political parties to prepare for the debates.

2.3 Were the debates effective, informative, and compelling?

The answer to this question is complex and in many ways subjective. People have varying conceptions of what makes debates effective, informative and compelling. To answer the question in the most comprehensive way possible, we rely on a mix of objective data, consultations we conducted with various stakeholders, and public reaction, as well as public opinion research we commissioned after the debates.

The first objective measurement of a debate's effectiveness is viewership. As we have seen, the LDC's 2021 debates attracted more than 14 million viewers, which is five million fewer than in 2019 but more than in 2015 and 2011. The Debates Broadcast Group (DBG) noted that the decrease in viewership reflects a decrease in television viewership across the board. Viewership may also have been impacted by lack of interest in the election, keeping in mind that voter turnout was also down in 2021 compared to 2019. Other possible factors: the election was held in the summer and therefore the debates were held early in September – a busy time for many Canadians; and COVID-19 affected the ability for broadcasters to be on site before the events, and therefore there was not as much media coverage leading up to the debates as in 2019.

The success of debates, however, is defined by more than the number of people who watch them. Debates are meant to create an environment where voters can better learn about party policies and evaluate the qualities of leaders: both their capacity to explain policies and their ability to perform under pressure.

There is widespread agreement that the 2021 debates did not deliver as well as they should have on informing voters about parties' policies. The two major weaknesses identified, especially with respect to the English-language debate, were format and moderation. Stakeholders we consulted and analysis that was publishedFootnote 10 criticized the format as being cluttered, restrictive and not allowing enough time for leaders to express themselves or to engage in meaningful exchanges. The consensus was that there were too many journalists on stage. Moreover, the line of questioning from the moderator and journalists limited the ability of leaders to expound on their positions.

Many Canadians were somewhat less critical. Polling conducted for the LDC by the CES show that 63%Footnote 11 found the debates informative. The moderation was also more favourably evaluated, with 77%Footnote 12 of viewers indicating that the moderators asked good questions and 79% indicating that they treated each leader fairly.Footnote 13 Still, 56% said there was not enough time provided to leaders to debate each other.Footnote 14 As one participant in a CES focus group remarked, "It seemed like they're just rushing through everything and no one is really getting answers."Footnote 15

Compared to non-debate watchers, those who watched the debates experienced increased:

- Trust in the federal government;

- Trust in political parties;

- Ability to rate party leaders;

- Updating in leader ratings;

- Election interest; and

- Confidence in voting decision.

However, the same survey showed that Canadians did not sufficiently learn about the parties' platforms during the debates. This is significantly different from the 2019 debates, when a similar survey conducted by the CES showed that viewers' knowledge of party platforms had been enhanced by watching the debates.Footnote 16

2.4 Were the debates organized to serve the public interest?

In determining whether the debates were organized in the public interest, it is important to distinguish between the organizational components of the debates and their substantive elements.

From a strictly organizational standpoint, the Commission believes it delivered on its mandate. The debates were organized according to the rules of public procurement, through an independent, public request for proposals process that selected the producer along clear criteria. The delivery of the debates was also well within the contracted budget.

On the substantive front, however, the debates were less successful in serving the public interest. This is defined in our OIC as an "essential contribution to the health of Canadian democracy."

We interpret the public interest in debates as responding to and serving the needs of the viewing public and, by extension, the voters. Our public opinion surveys reveal that what viewers want the most from debates is information on the platform positions of leaders and their parties that helps them make an informed choice at the ballot box.Footnote 17 Consequently, all the components of the debates should be fashioned to serve that need. They must enhance the delivery of relevant information to voters. This influences the type of questions that are asked of the leaders and the manner in which they are asked.

Framing the debates around the public interest also fosters trust. According to the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer, Canada is not a trusting society. We maintain overall a neutral attitude towards our institutions, with disinformation no doubt a contributing factor.Footnote 18 By providing a safe space where voters can evaluate party leaders in a live, unmediated format, debates can help build trust in institutions and foster citizen engagement. This is especially important for communities that feel disenfranchised or forgotten by the political process. Serving the public interest includes reaching people where they live, in languages other than French and English, and providing information that is relevant to their realities.

Section 3 – Beyond 2021

This section provides recommendations that seek to improve the mandate, role and structure of a future Commission or alternative independent body. It looks at what role this body can play, if any, in improving the production of the debates; and how it can, in collaboration with its partners, better serve the public interest.

While this independent body could take the form of the current Commission, there could be a number of institutional models worth considering over the longer term. We will look at these different models later. For the purpose of readability, we use the term Commission in the sections below.

While it has succeeded in making the debates more stable, accessible and transparent, the Commission has not fully achieved the goal of what we could call overall debate integrity. Debate integrity refers to a number of dimensions: participation criteria, reach, promotion, viewership, format, moderation, choice of themes and questions, mandate accountability, audience satisfaction and serving the public interest. For the debates to have integrity, each of these dimensions must be satisfied. Integrity implies the whole is greater than the sum of its parts and that overarching responsibility for the debates' success rests with a future Commission or independent body.

First, it is important to explore what needs to be accomplished and changed to improve each of the components of the debates.

3.1 Improving the leaders' debates in the next general election

There are three fundamental components related to the production of debates. For clarity, we are categorizing them below:

Format

The format pertains to the structural elements of the debate:

- Form (town hall, open debate, etc.)

- Number of segments and determination of segments (opening and closing statements, participation from audience, panels or guests, video packages, etc.)

- Timing: length of the debate, length of each segment, how long each leader has to answer a question, how much time should be devoted to each theme, length of open debate sections

- Number of questions posed to each leader but not the themes or topics of the questions

Moderation

The role of "moderator" refers to any person on the debate stage who:

- Steers or chairs the debate; OR

- Keeps track of timing; OR

- Engages with leaders by posing questions and follows up with questions to the leaders.

For greater clarity, a journalist who is on stage engaging with leaders, asking them questions and following up with questions to the leaders is a de facto moderator.

A member of the public who is seated in the audience or is live via video feed is not considered a moderator as they are not on stage with the leaders and are not engaging with them through follow-up questions and rebuttals.

Editorial

The editorial components of the debate include:

- Themes and questions to the leaders, including:

- Determining the themes and questions

- The order of the themes and questions

- The specific wording of each question

Essentially, editorial is what the leaders are talking about and which themes and questions they are being asked. Moderation is who asks these questions. Format is how (the mechanics of how the debate will unfold) and where (the logistics of the timing and run of show).

3.1.1 Format

There was widespread criticism of both 2021 debate formats by the media, public and various stakeholders.

Media coverage of the French-language debate focused on whether the debate had given rise to meaningful exchanges.Footnote 19 Criticism centered on the following:

- Busy format

- Too many questions

- Overproduced

- Too many journalists on stage

- Little opportunity for leaders to debate

The English-language debate received more negative media coverage and was marked by controversy over both format and moderation.

Media critics said the format was "restrictive"Footnote 20 and "tightly structured,"Footnote 21 giving leaders "too little time to explain their policies."Footnote 22 Commentators contended that the debate put too much emphasis on timing, had too many journalists on stage and provided no real opportunity for debate. The Globe and Mail likened it to a "press conference."Footnote 23

Public inputs received by the Commission underscored the same issues. Citizens wrote in with the following comments:

- "A debate is not a Q&A"

- "The format did not allow sufficient time for any leader to explain [their] position"

- "It shouldn't be a 'beat the clock' format"

- "This was purely crafted for TV ratings" and "'gotcha' soundbites that can be recycled on the nightly news"

- "The debate is not for showcasing journalistic talent" and "self-promotion"

A consensus emerged among the stakeholders consulted that the format was too rigid, too complex, too confusing, involved too many journalists on stage and did not sufficiently generate debate between the leaders.

Stakeholders said the combination of what were effectively five or six formats into one was difficult to follow. They also stated that the spotlight was often on journalistic talent instead of on the leaders.

Post-debate analysis showed there has been an increase in the number of questions posed in two-hour debates over time. In 2008, there were eight questions put to the leaders; in 2021 there were 45.Footnote 24 This data underscored the view that the debate had provided too much time for the moderator and journalists, and too little time for leaders. Others commented that the inclusion of questions from the members of the public contributed to the busyness of the format and provided limited value to the debate itself.

Both here and abroad stakeholders suggested the debate format should be simplified.

As noted above, a majority of citizens surveyed by the Commission asserted that their most important debate objective was to learn about the leaders' platforms.Footnote 25 As one participant in a CES focus group observed, the debates' objective "is to express and clearly show what [parties'] projects are, and what they are going to do for us."Footnote 26 The least important factor for Canadians was the need for a debate to "be exciting."Footnote 27

The Commission also received feedback about the issue of equal time for each leader and its potential trade-offs. A consensus emerged that there should be less emphasis on absolute equal time, but rather focus on being as fair as possible over the entirety of the debate. In other words, equal time should be incorporated as a principle rather than a mechanical approach.

Some stakeholders proposed eliminating the draw, the randomized determination of podium positions and order of questioning, and instead argued that this should be an editorial decision that is made to best serve the public interest.

The Commission concludes that the following format elements should be considered:

- Opening and closing statements;

- Same questions to all candidates in order to encourage debate between leaders;

- Time for follow-up questions to ensure leaders respond to the question asked;

- Open debate with all the leaders;

- Fairness rather than rigid adherence to equal time for all leaders; and

- Appropriate number and length of themes and questions to allow for in-depth discussion.

The question now is what role, if any, a future Commission should play in format issues.

In 2019, the Commission asked for an increased role for itself. In proposing to have the right of final approval on the format, the Commission's intention was not to impose a format on the networks, but to work with the debates producer to develop a format that would best represent the public interest. This was not possible in 2021 as the Commission received its new mandate in December 2020 and had to be ready for an election call as early as the spring of 2021. This short runway made it difficult for the Commission to work with stakeholders to develop and test potential formats or to get stakeholders onboard with the new process.

Our OIC says the Commission should have final approval of format while "respecting journalistic independence." In the context of the debates, we believe journalistic independence is more specifically defined as editorial independence, i.e. the editorial components of the debate as described above in section 3.1.

We believe it is an important responsibility for a future Commission to protect the editorial independence of the debates producer. But we do not believe format, the structural elements of the debate as outlined above in section 3.1., to be an editorial decision. We think a future Commission with no competing interests is best suited to develop a format that best serves the public interest. Having these discussions outside the pressure-cooker atmosphere of the months preceding an election call would also help in building efficiency and fostering trust in this democratic exercise.

NEW RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation #1: The Commission should have final approval over the format and should work with stakeholders between elections to develop a simplified format that best serves Canadians.

3.1.2 Moderation

There was strong consensus among the stakeholders consulted in 2021 that an effective moderator is central to the integrity of the debates and trust in democratic institutions.

Consultations highlighted that much of the success of debates rests with the moderator. This individual sets the tone of the debate and acts as the guardian of the public trust. It is important that they be neutral and keep the focus on the leaders. The moderator is on stage as a facilitator and is there to serve the voting audience.

Chris Waddell, former Director of Carleton University's School of Journalism and Communication and former CBC Television News parliamentary bureau chief and executive producer of news specials in Ottawa, wrote in his submission to the Commission that "invisibility should be the moderator's objective while holding a whistle that will be used infrequently but that participants know requires them to pay attention and follow orders when they hear it." Comparing the role of moderator to a "referee in hockey," he stated, "the best are ones the audience doesn't notice." Public inputs received by the Commission echoed this sentiment. "I have no interest in the opinion of the moderator," wrote one citizen. "We need to know the point of view of the party leaders," offered another.

Media commentators, public input and stakeholders we consulted proposed that the Commission should consider having a single moderator for future debates. Citizens put forward the same view, with the majority of Canadians surveyed by the Commission preferring a single moderator over multiple moderators.Footnote 28

International stakeholders and debate organizers noted the preference for a single moderator is a pattern that emerges over time. One moderator can use time most efficiently and more easily follow up with questions. A veteran debate organizer remarked that a moderator should have a reputation to lose, not a reputation to build. There was also consensus from stakeholders that fact-checking should largely be left to participating leaders.

When choosing a moderator for future debates, the Commission proposes it be someone who:

- Is experienced, familiar to the leaders, understands the major issues of the campaign, and has hours of live television experience and debate experience;

- Possesses the respect and trust of the leaders, as well as gravitas and intellectual depth;

- Is able to facilitate debate, elicit illuminating exchanges between the leaders, clarify the positions by asking follow up questions, and hold the leaders to account;

- Poses open-ended questions that prompt debate and promote discussion;

- Understands that the debate focus and attention is on the leaders;

- Serves the public interest and voting audience;

- Is able to control the discussion and move it along, interrupt when appropriate and avoid cross-talk; and

- Is non-partisan.

The role of the moderator is fundamental if debates are to serve the public interest above all else. The selection of debate moderators must therefore be done by an impartial and independent body, with no other competing interests.

By playing a central role, a future Commission should facilitate the choice of moderators by mitigating competing interests of media partners involved in the production of the debates. It has become almost customary for media organizations involved in the debates to expect to have one of their journalists on stage. A future Commission should propose the selection process of the moderators be made in a collaborative spirit with the producers of the debates. Once selected, a future Commission should ensure the moderators and the debates producer have full editorial independence over the conduct of the debates.

To ensure the independence of debates, political parties should not be consulted on the moderation and moderation choices. A future Commission should exercise due diligence and procedural transparency when undertaking the selection of the debate moderators.

NEW RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation #2: The Commission should select the debate moderator(s) based on expert consultations.

3.1.3 Editorial

The Commission believes editorial independence needs to be protected.

To respect the editorial independence of the debates, neither the Commission nor political parties should be involved in choosing the themes or the questions.

All editorial decisions – including debate themes, debate questions, specific wording of each question as well as the order of questions and themes – should continue to be made by the debates producer and debate moderators.

3.1.4 Number of debates

In 2019 and 2021, the Commission's mandate was to organize two debates, one in each official language. These debates, according to the Commission's OIC, were expected to "benefit from the participation of the leaders who have the greatest likelihood of becoming Prime Minister or whose political parties have the greatest likelihood of winning seats in Parliament."Footnote 29

Following the 2021 federal election, there were calls for more debates from the public, civil society and media commentators, especially in English Canada.

There was widespread consensus in post-debate consultations that the Commission should consider organizing more than one debate in each official language to address the imbalance experienced in 2021.

The Commission also heard that it should consider organizing additional debates to better serve the public interest. Stakeholders drew comparisons with international models, notably with the U.S., France, Germany and the UK, which all organized more than two debates in their last election cycles, scheduling debates with both the frontrunners and main party candidates. For example, Germany held four debates in the country's recent federal elections, three with the candidates running for chancellor and one with the seven parties in the Bundestag. The UK organized at least five debates in its last general election in 2019, holding debates with both the main party leaders or leading figures of those parties and with the frontrunners.

Results of the CES study show that citizens favour two debates in each language in a five-week campaign, preferring to hear from a broader range of leaders.Footnote 30 While this is the popular view, the Commission also heard concern that this would require the agreement of the political parties and television networks. Invited leaders may not be willing or available, and networks may not commit to broadcasting multiple debates due to revenue losses from cancelling regular network shows. Stakeholders also evoked the short Canadian election campaigns as another possible impediment to holding more debates.

Ratings in 2021 show that more debates may not splinter the viewing audience. The TVA debate attracted a large audience without eroding the number of people who tuned in to LDC's French-language debate. International debate ratings also remained high despite multiple debates.

Some stakeholders suggested Canada should consider looking at two different types of debates similar to European countries. They offered that having the opportunity to hear from leaders most likely to form government and become prime minister may have a lot of appeal for Canadians. International experience suggests that such a debate model works well elsewhere. In the Canadian context, there may be some challenges associated with this view, namely the willingness or availability of invited leaders to participate, the possibility of fracturing the viewing audience, and practical difficulties associated with shorter electoral campaigns. Canada's electoral history may provide some basis for determining who might be part of a frontrunners' debate (i.e. parties that are most likely to form government). This approach would require not only a cultural shift for the country and buy-in from the political parties and broadcasters, but also the setting on a clear and objective basis of two different sets of participation criteria.

The Commission also heard feedback that it should consider the possibility of organizing debates on specific topics. While there may be future demand for additional debates on specific issues (in our view a very desirable outcome), these could be hosted by other organizations and may involve senior party representatives. Such endeavours should be encouraged through the lending of expertise and by providing advice in terms of toolkits or manuals, thereby stimulating the evolution of debates in Canada.

Fundamentally, the spectrum of inputs received during this past election cycle and throughout the post-debate consultations showed that a majority of Canadians want more debates. As a result, the Commission believes that it should consider organizing more than two debates, one in each official language, provided additional funding is made available. These could be more debates with qualified party leaders or debates with the frontrunners. If a future Commission is responsible for organizing and encouraging more debates beyond the two currently in its mandate, it should have the authority to do so to ensure that Canadians are best served.

NEW RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation #3: The Commission should organize two publicly funded leaders' debates (one in each official language) and have the ability, funding and authority to consider organizing additional leaders' debates where feasible. It should also have the ability to provide advice and expertise to other debate organizers.

3.1.5 Participation criteria

In 2021, the Commission was tasked with selecting the party leaders who would be invited to participate in its debates.

The Commission undertook this task by consulting with registered political parties, stakeholders, and the public. It also considered the historical application of debate participation criteria in past Canadian elections; the 2019 participation criteria; existing public policy documents on debate participation criteria; and submissions from stakeholders, including the leaders of all registered political parties, the media and the public.

As a result of this process, the Commission developed principles to guide the creation of its participation criteria. The Commission concluded that the criteria should, to the greatest extent possible:

- Be simple;

- Be clear;

- Be objective; and

- Allow for the participation of leaders of political parties that have the greatest likelihood of winning seats in the House of Commons.

On June 22, 2021, the Commission announced its decision and provided supporting rationale.Footnote 31

In order to be invited by the Commission to participate in the 2021 leaders' debates, a leader of a political party was required to meet one of the following criteria:

(i): on the date the general election is called, the party is represented in the House of Commons by a Member of Parliament who was elected as a member of that party; or

(ii): the party's candidates for the most recent general election received at that election at least 4% of the number of valid votes cast; or

(iii): five days after the date the general election is called, the party receives a level of national support of at least 4%, determined by voting intention, and as measured by leading national public opinion polling organizations, using the average of those organizations' most recently publicly reported results.

On August 16, 2021, the Commission also made public how it would apply criterion (iii), along with a detailed rationale.Footnote 32 The objective of the release of this information, ahead of the election call, was to increase transparency around which polls the Commission would use to measure a party's level of support and how these polls would be averaged.

On August 21, 2021, the Commission issued its decision on the application of the participation criteria and invited five party leaders to participate in its debates.Footnote 33 This decision was made following the Commission's request for and receipt of advice from a Polling Advisory Group convened by Peter Loewen, who in addition to co-leading the CES for the 2021 federal election, is a professor in the Department of Political Science and the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, Associate Director, Global Engagement at the Munk School, and Director of PEARL (Policy, Elections, & Representation Lab).

All five invited leaders participated in the Commission's debates.

Stakeholder reaction and post-debate consultations indicated broad satisfaction with the criteria and the process by which the Commission communicated its approach and its decisions. Writer and polls analyst Éric Grenier commented that the Commission had chosen "simple, objective criteria that could be employed in future elections."Footnote 34 The leader of the People's Party of Canada, Maxime Bernier, indicated that the Commission's criteria were "clear and objective."Footnote 35

Based on its 2021 experience, the Commission concludes that having the mandate to set participation criteria for the debates it organizes is appropriate and contributes to ensuring debates are organized in a non-partisan, predictable and transparent manner for future elections. Several components of its approach to setting and communicating these criteria in 2021 should be considered in future mandates.

In terms of setting the criteria, the Commission remains of the view that debate participation criteria should be established to measure both a political party's historical record and its level of current and future electoral support. That is because: (a) both can be used to assess whether a political party is likely to play an important part in policymaking by winning seats in the House of Commons, and (b) such an approach is consistent with the historical application of debate participation criteria in Canada. The Commission continues to believe that political parties should only be required to meet the criteria for one or the other, and not both. This enables, on the one hand, the potential participation of a newly emerging political party that may be unable to meet criteria based on a historical record, and on the other the participation of a political party with a demonstrated historical record.

The specific criteria set by the Commission for the 2021 debates were seen by a few as too high a bar for debate participation, and by a larger group as too low a bar. However, many stakeholders expressed that the selected criteria were appropriate. The Commission concludes that, to the extent future participation criteria should allow for the participation of leaders of political parties that have the greatest likelihood of winnings seats in the House of Commons, the 2021 criteria provide a useful reference and could be re-used in future elections.

In terms of applying the criteria and inviting leaders, the following components should be considered again in the future: the use of expert advice on the selection and averaging of public opinion polls, the use of as many polls as possible, and the articulation in advance of the election call of the requirements that must be met for a poll to be included in the Commission's analysis.

It is important to ensure that the date upon which parties' levels of national support are measured is as close to the date of the debates as possible. The 2021 criteria specified that this determination was to be made five days after the date the election was called; this meant the first debate took place 18 days after the Commission made its determination on parties' levels of support. In the context of an electoral campaign, this can provide, in some elections, enough time for there to be a measurable change in a party's level of support. The Commission recognizes that sufficient time between the final participation decision and the debate dates must be provided to ensure the debates producer can produce a high-quality debate, as required by the OIC, and that the political parties can properly prepare for the debates. However, a future Commission should continue discussions with both groups with the goal of narrowing this timeframe and making the final participation decision as close as possible to the debates.

Future participation criteria should aim to use the latest polls possible as a basis for determining levels of support, while still ensuring that a range of polling firms' data are used and averaged. If timing permits, this could suggest the use of only those polls released after the election is called. Additionally, in order to provide the greatest degree of transparency and predictability possible, a future Commission could explore the feasibility of not only identifying the criteria by which polls will be judged suitable for inclusion – which we did this time – but also of naming the specific polling firms that will be included.

Should a mandate be provided to consider organizing more debates, it is conceivable that a different set of guiding principles could be applied for these additional debates, such as considering: greatest likelihood of forming government instead of greatest likelihood of winning seats in Parliament. Further analysis would need to be done on the precise thresholds and methods that could be set to achieve this outcome, but a threshold of inviting leaders of those parties that have at least 20% national support in an aggregate of current public opinion polls could be a starting point to begin consultations. Any such criteria would need to be simple, clear, and objective.

REAFFIRMED RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation #4: Participation criteria should be as objective as possible and made public before the election campaign begins. The criteria should be set by the Debates Commissioner.

3.1.6 Measures to encourage participation

In 2021, as in 2019, all leaders invited to participate in the debates organized by the Commission were in attendance. While it is undeniable that there are always factors beyond a debate organizer's control with regards to leader participation, the Commission remains of the view that no special measures are needed on the part of Government to encourage leader participation.

The Commission remains of the view that the best ways to encourage participation are to:

- Deliver a large audience for the debates;

- Engage with leaders and political parties in advance of the election;

- Create a climate of expectancy and stability; and

- Make debate invitations and responses from parties publicly available.

REAFFIRMED RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation #5: Political parties should be encouraged rather than compelled to participate in leaders' debates.

3.1.7 Debates procurement

Background

In both 2019 and 2021, the debate producers were selected through a request for proposal (RFP). The purpose of the RFP was to contract the promotion, production and distribution of two debates for the next federal election, one in each official language. Contractors were welcome to bid on either the English-language debate, French-language debate, or both. The RFP was open to sole entities or to joint ventures, but organizations were encouraged to work together in an effort to ensure the debates reached as many Canadians as possible.

Once contracted, the Debate Broadcast Group (DBG) took full responsibility for the promotion, production, and distribution of debates while maintaining regular communications with the Commission.

The Commission approved the formats submitted and moderators proposed, but it was not involved in determining the themes or questions for the debates as these responsibilities were delegated to the DBG.

Should a future Commission undertake a greater role as it relates to the format and moderation, as suggested above, its approach to contracting should evolve slightly. Rather than defining its expectations in the RFP, a future Commission may want to evaluate bidders on experience and capability alone. A future Commission would in turn select an experienced and capable partner, with whom it would work collaboratively to develop the format while retaining final approval authority.

Future process

The DBG has indicated that the RFP process is onerous and that the bid should be simplified. They also suggested the RFP should be released as early as possible to give bidders more time to submit and to spread the workload out before the writ drop.

The group of media organizations that formed the debates producer in both 2019 and 2021 was able to reach an impressive number of Canadians. The direct link to these audiences is important and cannot be taken for granted. However, it is important to note the consortium approach is not without compromise.

Stakeholders suggested to the Commission that having only one broadcaster produce the debates may lead to better debates, as it would make workflow, choice of one single moderator and even production choices more streamlined. The Commission also learned through its consultations process that the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC)lays an integral role in debate production. A few stakeholders consulted went as far as to say that the public broadcaster may be the only broadcaster to have all the necessary in-house skills to bid successfully on the RFP as it is currently structured. This is worth noting as it may be relevant to future policy decisions.

In its post-debate consultations, the Commission examined and considered different types of procurement. As the last two RFPs netted similar results, an argument could be made for a directed contract (e.g. sole source). Some stakeholders consulted said they preferred this approach.

In considering the option of a directed contract, the Commission consulted with Public Service and Procurement Canada (PSPC). They suggested that a competitive process remains the best way for a future Commission to select a debates producer because it is fair, transparent and competitive.

The Commission agrees with the assessment that a competitive process remains the best way to select the debates producers. However, the RFP could be simplified to solve some of the problems encountered in the last two cycles.

The 2019 and 2021 RFP focused on specifics. It defined what the Commission expected from the debates producer and included detailed deliverables. When it came to the choice of moderator and format, for instance, the Commission was specific about its expectations.

In 2021, bidders were asked to submit a format and select a moderator who achieved the outlined objectives. By evaluating the bid with those specifics defined, the process gave the perception that the bid – and therefore the choice of moderator and the format – were "rubber stamped" by the Commission. This did not allow for such important and creative choices to be fluid, dynamic and responsive to learning.

Instead of being prescriptive, a future RFP could focus on evaluating the experience and capabilities of bidders. It should clearly state a future Commission will work together with the debates producer on key decisions such as developing a format that better serves the public interest while retaining final approval. Those important decisions should not be part of the bid, but be made collectively, with the Commission having ultimate responsibility.

A future RFP should evaluate bidders' attributes, experience and ability to do what is required, rather than an actual proposal of what they are going to do. The RFP should specify those areas in which a future Commission will be involved (e.g., developing the format and selecting a moderator), and those areas in which it will not (e.g., choice of themes and questions).

Distribution remains an important part of the debates' success and an area where the DBG provided large in-kind contributions. As we will see in the next section on languages and accessibility, the ability of a debates producer to pull together diverse groups (e.g., APTN, OMNI, etc.) is a key factor in reaching audiences. Language distribution should continue to be a highly rated or even mandatory criterion in the RFP. The Commission should also ensure that it has the freedom to enter into multiple contracts. For instance, there could be an RFP for promotion, production and distribution and separate contracts for distribution for specific languages or formats.

Like distribution, debate promotion remains an important part of the debates' success and an area where the DBG provided large in-kind contributions. Promotion should continue to be a mandatory component of the RFP and should be weighted heavily in the evaluation criteria.

REAFFIRMED RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation #6: A competitive process should continue to be used to select the debates producer.

3.1.8 Media accreditation

In 2021 as in 2019, the Commission was responsible for the accreditation of journalists to the debates. This accreditation provided access to the press room, where journalists can watch the debates and to the press conference room, where they can interview the leaders after the debates. Since these press conferences are broadcast live on a number of television networks, the Commission considered them as part of the overall broadcast environment of the debates in respect of which high journalistic standards must apply.

The following excerpt of our media accreditation policy, published in August 2021, explains the Commission's reasoning:

"In order to protect the integrity of the debates, the principles of high journalistic standards and journalist independence must extend to the press availabilities of the leaders held immediately after the debates when each leader takes questions from journalists. These press availabilities are broadcast live to millions of viewers and, as such, are a natural extension of the debates and an integral part of the press coverage of the events. Consequently, the Commission believes it is reasonable to expect that the journalists accredited to the debates and the press availabilities, both in a physical or virtual environment, adhere to the standards of professional journalism."

The Commission considers the debates as rare, privileged moments of a campaign where voters can hear from political leaders in real time and in an unmediated, unfiltered, and undistorted way. To achieve this, the debate environment must be free of disinformation and other forms of manipulation.

The Commission recognized that it doesn't have the authority to decide by itself whether journalists adhere to the ethical standards of their profession. Consequently, it relied on the codes of ethics of five professional journalistic organizations for its accreditation process: the Canadian Association of Journalists, the News Media Council, the Parliamentary Press Gallery, the Québec Federation of Journalists and the Québec Press Council. These organizations cover the vast majority of journalists involved in coverage of federal election campaigns. Members of these organizations were automatically given accreditation to the debates.

In order not to penalize journalists who do not belong to these organizations, the Commissions made provisions for accreditation applications from other journalists, including from other countries. Applicants had to provide examples of their work to ascertain that they are professional journalists. The Commission would then evaluate their work to determine whether it was free of conflict of interest. It relied for this on the guidelines of the Canadian Association of Journalists.

According to the CAJ, there is a conflict of interest:

• when an organization:

- becomes an actor in the stories it tells, including providing and applying financial and legal assistance to some of its sources to work toward a desired outcome or offering free legal services, crowdfunds to help some individuals in stories hire lawyers, purchases political advertising and launches petitions;Footnote 36

Or

• when a reporter:

- writes opinion pieces about subjects they also cover as journalists, endorses political candidates or causes, takes part in demonstrations, signs petitions, does public relations work, fundraises and makes financial contributions. Footnote 37

The Commission opened the accreditation process the day after the writ drop. Journalists had 10 days to apply. In addition, in advance of the debates, the Commissions' COVID-19 protocol with respect to attending the debates in-person were publicly available.

The Commission received 110 applications for the French language debate and 116 application for the English language debate. Of these applications, the Commission denied a total of 16 applications that sought accreditation for both debates.

In particular, the Commission rejected the applications of representatives of one organization, Rebel News Network ("Rebel"). The Commission determined that the Rebel website violated the articles of conflict of interest of the Canadian Association of Journalists. The Commission found that Rebel was in a conflict of interest because it becomes an active participant in stories it covers by launching petitions, fundraising and engaging in litigation on issues that it reports on regularly. Rebel also embeds links to its petitions and fundraising campaigns within its articles and videos.

Rebel applied for and obtained an emergency injunction from the Federal Court that obligated the Commission to accredit its members to the debates. The Federal Court ruled that Rebel "has satisfied the test for an interlocutory mandatory injunction." Reasons from the Federal Court are pending.

The Commission also rejected the accreditation of representatives of Rebel News Network in 2019 because it considered that Rebel News Network and another applicant, True North, were involved in advocacy. Rebel and True North obtained an emergency injunction, which required the Commission to approve their accreditation requests. In that case, the Federal Court ruled that denying the applicants accreditation would cause irreparable harm to their ability to cover the debates. After the 2019 debates, Rebel sought to continue with its application for judicial review. The Commission in response brought a motion to strike the application on the ground of mootness, which the Federal Court granted. Rebel then appealed the mootness motion decision to the Federal Court of Appeal. At present, Rebel is in the process of discontinuing its appeal.

In the absence of a ruling on whether it has the authority to determine criteria for media accreditation and the manner to do so, the Commission now finds itself confronted with a judicial void. The first ruling, in 2019, faulted the Commission on its procedural mechanisms. The Commission believed it had adequately addressed this issue in the 2021 debates by, among others, publishing in advance criteria against which applications would be evaluated. However, the court again granted an injunction forcing the Commission to accredit media entities that the Commission views to be in a conflict of interest. At the writing of this report, the Federal Court's reasons for the 2021 injunction proceeding are still not known. Accordingly, the Commission has limited guidance on whether it has properly addressed the question of due process. Whether the media accreditation process violates expressive freedoms remains an open question. In its decisions on individual applicants, the Commission found that the impact on an applicant's freedom of expression was outweighed by the salutary effect of the Commission carrying out its mandate or upholding high journalistic standards.

The Commission continues to view its media accreditation policy as reasonable and an appropriate exercise of its delegated authority. It is the Commission's duty to provide for Canadians a debate environment free from disinformation, manipulation, or conflicts of interest as prohibited by the relevant professional journalist associations.

Regardless, the Commission faces a dilemma: to continue to be responsible for media accreditation at the risk of being overturned by the courts, or approve all accreditation requests regardless of the applicants' qualifications as professional journalists. This would mean that anybody who claims to be a journalist could be accredited to the debates, regardless of any qualification or a reasonable vetting process.

In the absence of a ruling on its authority over the media accreditation process (including the "scrum" after the debates) and the applicable criteria thereto, the Commission is not in a position to make a recommendation at this time. We have outlined above an issue that will have to be resolved before the next debates. Whether this authority to accredit media properly should rest with the Commission is yet to be determined.

3.1.9 Languages & accessibility

The Commission's OICs state:

"It is desirable that leaders' debates reach all Canadians, including those with disabilities, those living in remote areas and those living in official language minority communities"Footnote 38 and that the Commission should "endeavour to ensure that the leaders' debates are available in languages other than French and English, and, in doing so, pay special attention to Canada's Indigenous languages."Footnote 39

For the leaders' debates to be a democratic exercise, citizens must be able to access and experience the debates in an accessible way. To reach as many Canadians as possible, the Commission must ensure the debates' signal reaches as many Canadian households as possible; that Canadians are able to watch, listen or read the debates in a language and format that is accessible to them; and that the debates allow them to engage in a way that makes them feel that the debates are for them.

In 2021, both debates were translated into French and English as well as into 14 other languages, including six Indigenous languages, ASL and LSQ. They were also available in closed captioningFootnote 40 and described video.

| September 8 French debate TV |

September 8 French debate digital |

September 9 English debate TV |

September 9 English debate digital |

TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASL | Not offered | 1,364 | Not offered | 26,841 | 28,205 |

| LSQ | Not offered | 7,022 | Not offered | 561 | 7,583 |

| Described Video | 23,000 | 437 | 14,000 | 4767 | 42,204 |

| Arabic | Data not available | 476 | Data not available | 349 | Data not available |

| Cantonese | 15,000 | 761 | 2,000 | 938 | 18,699 |

| Denesuline | Not offered | Not offered | Data not available | 1,141 | 1,141 |

| East Cree | Not offered | Not offered | Data not available | 508 | 508 |

| Innu | 16,000 | 471 | Not offered | Not offered | 16,471 |

| Inuktitut | Not offered | Not offered | Data not available | 546 | 546 |

| Italian | 7,000 | 406 | 11,000 | 163 | 18,569 |

| Mandarin | 3,000 | 707 | 21,000 | 1,271 | 25,978 |

| Ojibway | 5,000 | 839 | Not offered | Not offered | 5,839 |

| Plains Cree | Not offered | Not offered | 1,000 | 1,104 | 2,104 |

| Punjabi | 4,000 | 1,737 | 27,000 | 1,729 | 34,466 |

| Tagalog | 15,000 | 3,723 | 35,000 | 1,344 | 55,067 |

In 2019 and 2021, language interpretation was included in the request for proposal (RFP), making it the responsibility of the debates producer. In 2021, the Debate Broadcast Group (DBG) included the addition of the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) as part of the partnership, and OMNI as a distribution partner. These networks were key to the success of language interpretation and distribution. A future Commission should work with the debates producer and stakeholders to explore a way to offer ASL and LSQ on television, in addition to making it available digitally.

To best serve non-official language communities, a future Commission should develop relationships and contracts with broadcasters and partners who have strong existing relationships with these communities. A future RFP could evaluate bidders not only on their ability and commitment to provide interpretation and translation, but also on whether they can guarantee distribution and promotion to those important communities. As noted above, a future Commission should maintain the freedom to have additional contracts with distributors and organizations to ensure the feed of these languages finds the right audience.

Following the 2021 election, the debates producers told the Commission that translation was one of the most onerous parts of the debate production. The DGB worked directly with the Translation Bureau, and both parties said the relationship was positive and productive. Translation represents about 25% of the production budget. The Bureau said there would be no cost efficiency to removing the translation from the RFP (and having it rest with a future Commission). However, the Commission heard from the Translation Bureau and the debates producer that language interpretation is an area that would benefit from a longer runway.

In post-debate consultations, the Translation Bureau talked of the benefit of having contact between election cycles. This would allow policy development for the choice of Indigenous languages, and for the Bureau to work with Indigenous language and ASL and LSQ interpreters to get them "debate ready" before the debate. It would also provide the ability to test production decisions related to interpretation, and to develop an outreach campaign for the specific Indigenous language communities. This would lead to better representation of Indigenous languages because the languages would be chosen based on population and communities served, rather than on availability of qualified interpreters.

The Translation Bureau indicated that for many of the simultaneous translators, interpreting a debate is "the greatest event of their career." Having a relationship between election cycles would allow amplification of this investment by connecting interpreters with other departments in government while they are in the national capital region for the debates, and to work with the interpreters to develop outreach campaigns.

In consultations with the Department of Canadian Heritage, the Commission learned that the Indigenous Languages Act (ILA) is in the early days of operationalization, working to create a policy on Indigenous language translation and interpretation. The government department says it considers the debates to be one of the most high-profile initiatives in the space, noting that a future Commission would be able to share findings from its experience.

REAFFIRMED RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation #7: Debates should continue to be available in French, English and other languages, paying special attention to Canada's Indigenous languages.

3.2 Improving a future Debates Commission

3.2.1 Debates promotion and citizen engagement

In 2019, the Commission tested three different outreach and promotional models and learned that the most effective and cost-efficient way to promote debates was to incorporate promotion into the request for proposal (RFP) for the debates producer.

In 2021, promotion for the debates – how, where, when, why to watch – was part of the debates producer's scope of work. The DBG promoted the debates on all channels and platforms.

The promotional strategy for the debates was also directly linked with production and distribution. As a result, debate promotion focused on infiltration through distribution, and promotion of that infiltration. As noted, the debates aired live on 36 television networks, four radio networks, and more than 115 digital streams. This level of distribution is advantageous because it reaches people who do not typically engage in politics. Like the Super Bowl, or the Oscars, even people who did not watch the debates were aware that they were happening or had happened. This is important because research shows that people who watched even just part of the debates experienced an increased ability to rate party leaders, and an increased election interest and increased interest in politics more generally.Footnote 41

With promotion firmly in the hands of the debates producer, the intention was to focus outreach efforts on stakeholder engagement with specific communities. The strategy was to develop an outreach campaign to promote Indigenous languages, accessible formats, and non-official languages.

However, with the snap election call coming shortly after the Commission restarted its operations, we had to focus on the main priority of debate production, and there was insufficient time to enter into outreach contracts. Previous sections on reach, languages and accessibility have outlined the Commission's suggestions for how to move forward in this area.

In the future, there should be a focus on ensuring distribution partners for Indigenous languages, ASL, LSQ and non-official languages to maximize reach in these communities. Work can be done "off cycle" to develop relationships with organizations who are leaders in specific communities: Canadians living with disabilities, ethno-cultural groups (to promote various language offerings), Indigenous groups (to promote Indigenous language feeds) and youth (to promote and create political awareness in the next generation). A focus in these areas aligns with CES findings that more work could be undertaken to build awareness of debates in future federal elections.Footnote 42

This "off cycle" work is particularly important in a minority government context as it would effectively allow a future Commission to be ready to "press play" in a snap election. It is unlikely that an entity that is recreated less than one year before an election will have the time to develop contacts, relationships and resources or outreach contracts with organizations for outreach purposes.

Minority government context and off-cycle considerations

In post-debate consultations, the Commission repeatedly heard that there is work to be done between elections. Whoever is entrusted with the public trust of debates needs to maintain some permanent capacity between elections to ensure it can organize debates in minority government situations, maintain relationships with interested parties between elections and foster discussion about best practices in debate formats and production, both in Canada and in other countries.

The DBG said the request for proposal and contract should be released and awarded as early as possible. This would allow the debates producer to secure the venue, hire interpreters, begin production design and work with the entity to set the debate dates.

In 2019 and 2021, the Commission received advice and guidance from the Canadian Cyber Centre at the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), an organization with a mandate to examine threats to the democratic process. In its publication, "Cyber threats to Canada's democratic process: July 2021 update,"Footnote 43 the CSE outlines that democratic processes remain a popular target for threats. Election Canada's Public Opinion Research Study on Electoral MattersFootnote 44 found that that 78% of respondents saw "false information online" as one of the factors that could have the most impact on the 2021 election.

CSE noted that it would like to offer more services to protect the debates and get involved earlier in the process – at least 12 months before the debates – to ensure that the advice they provide is actionable. It also recommended that the selection of the debate dates and location be made as early as possible, and possibly be separated or removed from the debates producer RFP. This would allow "off cycle" work between CSE and the venue to occur separately from the procurement process.

CSE also proposed an ongoing relationship with the debate venue. This, they contend, would allow cyber security to be considered in all areas of the debate organization – such as IT infrastructure at the debate venue – and not only with the television broadcast of the debate.

While the Commission has taken action to try to combat disinformation in both 2019 and 2021 (hosting and promoting verified debate video on its website, working with CSE to ensure the debate broadcast feed is protected, etc.), there is more that could be done in this space to strengthen the cybersecurity of the debate venue and broadcast feeds and to ensure the digital spaces broadcasting the debate are safe spaces, free of disinformation. Some social media platforms do not allow broadcasters to limit comments from the public. There was concern that the comments on debate digital pages could spread misinformation. A future Commission could work with digital and social media platforms to combat misinformation and create a safe space to host the debates digitally.

As noted above, the Translation Bureau had similar feedback for the Commission. The Bureau suggested an operational existence between cycles to better serve Indigenous language communities. They also put forward a request that debate dates and location be set as early as possible. In a majority government context, they advocated for fixed debate dates.

Off-cycle work through the establishment of a permanent capacity between election cycles could include:

- Working with the Department of Canadian Heritage and Statistics Canada on a population-based policy for Indigenous interpretation;

- Working with the Translation Bureau to select and train interpreters for debates;

- Working with Indigenous leaders and communities to promote Indigenous language offerings;

- Selecting the debate venue;

- Consulting with the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security to ensure cyber security of the debate venue and debate feed;

- Working with stakeholders to ensure debate integrity and combat disinformation around debates;

- Consulting with debate organizers internationally on best practices on format and moderating;

- Testing debate formats;

- Selecting and developing potential moderators;

- Providing advice and guidance to other debate organizers;

- Cultivating stakeholder relationships; and/or

- Developing outreach contracts to ensure all Canadians – even those especially underserved – engage with leaders' debates.

NEW RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation #8: The Commission should maintain sufficient permanent capacity between elections to ensure it can organize debates at short notice and to cultivate relationships between elections to foster discussion, both in Canada and in other countries.

3.2.2 Summary of expenditures

The Commission received a budget of $5.5 million from the Government for each of the 2019 and 2021 election cycles. In 2019, of this amount, it spent approximately $3.9 million, and in 2021, $3.5 million. Categories of expenditures and comparisons to the 2019 cycle are as follows:

| Activity | First mandate (2019 debates) Actual * ($ millions) |

Second mandate (2021 debates) Preliminary estimate ** ($ millions) |

|---|---|---|

| Research, evaluation and outreach initiatives | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Professional services | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Contract for incremental costs for debate production | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Commission salaries and administrative expenses | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Privy Council Office administrative expenses | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Total | 3.9 | 3.5 |

* Actuals are the authorities used in the current fiscal year published in the public accounts of 2018-2019 and 2019-2020.

** Preliminary estimates are the authorities used in the current fiscal year published in the public accounts of 2020-2021, and an estimate for 2021-2022. Figures may not add up to totals due to rounding.

In 2021, research, evaluation, and outreach initiatives included research undertaken by the Canadian Election Study (CES) consortium. There were no expenditures on outreach initiatives, which is a departure from 2019.

Professional services included legal services, website coding, report editing and layout.

Contract for incremental costs for debate production included funding for services that are above and beyond the historical expectations of a debates producer (e.g.: the obligation to distribute the signal freely, alternative formats for accessibility, language interpretation). The DBG absorbed costs that – historically – have been incurred by debates producers (e.g. staffing, promotion, remotes, connectivity, and technical distribution).

Commission salaries and administrative expenses included those expenses related primarily to employee services (one full-time and four part-time staff, including the Debates Commissioner) and support to the seven-person Advisory Board.

Privy Council administrative expenses included the provision of back-office support in relation to procurement, finance, information technology, personnel, and accommodations.

As in 2019, the Commission benefitted from significant in-kind contributions from the debates producer and partner organizations. These additional contributions, valued at approximately $3 million, also involved extensive debate promotion by the DBG.

3.2.3 Future mandate, authorities and governance

The Commission has now been responsible for the organization of leaders' debates in the last two federal election campaigns: 2019 and 2021. After the 2019 experience, the Commission recommended to the Government that it eventually be made permanent through legislation.